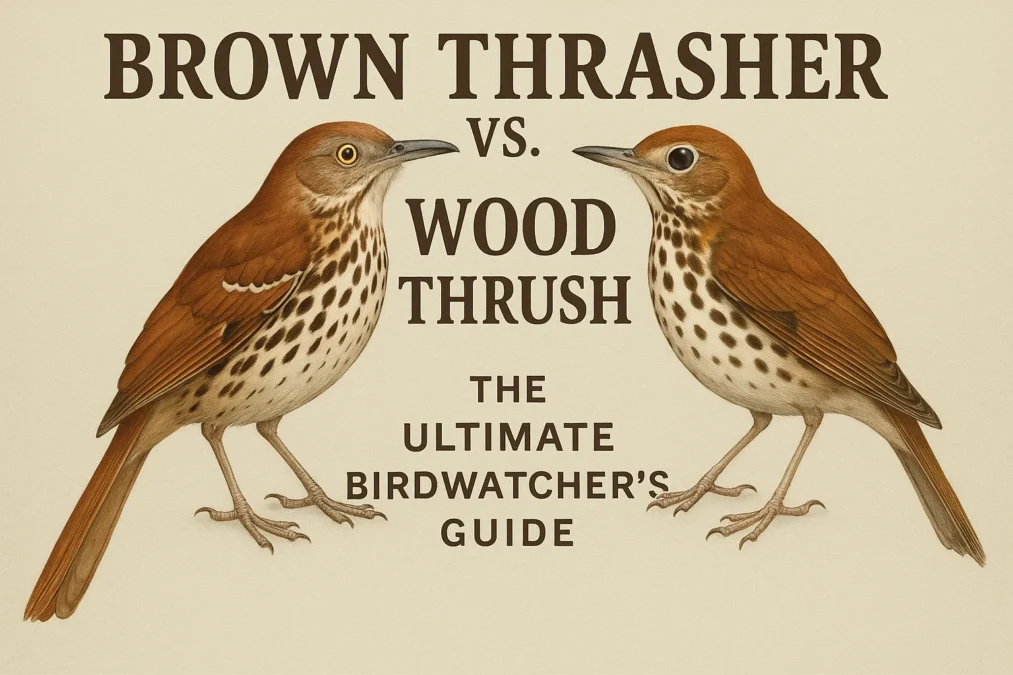

The dappled sunlight of a eastern forest or the tangled brush of a suburban backyard can present a birdwatcher with a delightful challenge: was that a melodious, flute-like song from a Wood Thrush or a chaotic, joyful ramble from a Brown Thrasher? For beginners and even some seasoned enthusiasts, distinguishing between a brown thrasher vs wood thrush can be a tricky task. Both are predominantly brown birds, both possess stunningly beautiful songs, and they can sometimes even occupy overlapping territories. However, once you know what to look and listen for, telling them apart becomes second nature.

This guide is designed to be your comprehensive resource. We won’t just skim the surface; we’ll dive deep into the lives of these two remarkable species. We’ll explore every facet of their existence, from the intricate patterns on their breasts to the complex syntax of their songs, from their chosen habitats to their migratory secrets. By the end of this journey, you won’t just be able to identify them—you’ll appreciate the unique ecological roles they play and understand the subtle wonders that differentiate a thrasher from a thrush. So, grab your binoculars, and let’s unravel the mystery of the brown thrasher vs wood thrush.

Meet the Contenders: An Introduction to Two Distinct Families

Before we pit them against each other, it’s crucial to understand that despite some superficial similarities, these birds belong to completely different families. This fundamental taxonomic difference explains nearly all of their contrasting behaviors and physical traits.

The Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) is a proud member of the Turdidae family, a group known as the “true thrushes.” This aristocratic avian family includes other celebrated songsters like the American Robin, the Eastern Bluebird, and the Hermit Thrush. True thrushes are often characterized by their upright posture, spotted breasts (in juveniles and adults of some species), and their world-renowned, melodious vocalizations. They are the poets of the bird world, their songs often described as ethereal and hauntingly beautiful.

The Brown Thrasher (Toxostoma rufum), on the other hand, is a member of the Mimidae family. This is the family of mimics, which includes the Northern Mockingbird and the Gray Catbird. Mimids are the clever tricksters and virtuosos of the avian realm. They are known for their incredible vocal mimicry, immense song repertoires, and often more skulking behavior in dense, shrubby habitats. While they may share a general brown coloration with thrushes, their posture, bill shape, and overall demeanor are distinctly their own. Understanding this family divide is the first and most important step in the brown thrasher vs wood thrush identification puzzle.

A Study in Subtlety: Visual Identification and Physical Features

At a fleeting glance, both birds present a rusty-brown appearance. But a closer look reveals a world of difference in their size, structure, and markings. Training your eye to spot these key features will allow for confident identification even before the bird sings a single note.

The Brown Thrasher is a large, slender songbird with a long, elegant tail that accounts for almost half its body length. It typically measures around 11-12 inches from beak to tail tip, making it noticeably larger than the Wood Thrush. Its back is a warm, rufous-brown, and its underside is a white or creamy buff, but the most defining feature is the heavy, dark brown streaking—not spotting—on its breast and belly. These streaks look almost as if someone took a fine-tipped brush and made long, deliberate downward strokes. It has a bright yellow eye, giving it a rather fierce, intense expression, and a long, slightly downcurved bill, perfectly designed for its foraging style.

The Wood Thrush presents a completely different structure. It is a more compact, pot-bellied bird with a shorter tail, typically measuring about 7.5-8.5 inches. Its posture is often more upright, like a tiny aristocrat. The most stunning feature of the Wood Thrush is its underparts. Its white breast and flanks are adorned with large, dark, well-defined spots that form distinct black streaks on its sides, creating a beautiful and intricate pattern. Its head is a more neutral brown, contrasting with its richer, reddish-brown back and crown. Its face is soft, with a gentle expression, and it lacks the thrasher’s intense yellow eye, sporting a dark one instead. Its bill is shorter, straighter, and perfect for plucking invertebrates from the leaf litter.

The Sound of Music: Decoding Their Songs and Calls

If visual identification is the first chapter, then auditory identification is the entire novel. The songs of these two birds are their most famous feature, and they could not be more different. Learning to distinguish them by ear will open up a new dimension in your birding experience.

The song of the Wood Thrush is often considered one of the most beautiful sounds in nature. It is a flute-like, melodic series of phrases that evokes a sense of deep, peaceful wilderness. The song is characterized by its ethereal, ringing quality and is often described as a “ee-oh-lay” or a series of musical notes with a haunting, bell-like echo. The thrush actually produces this dual-toned sound simultaneously by controlling the two sides of its syrinx (avian voicebox) independently. It typically sings in short, spaced-out bursts of three or four phrases, each phrase often ending with a complex, vibrato trill. It is the sound of a pristine, mature forest at dawn or dusk.

Conversely, the Brown Thrasher is the rock-and-roll guitarist of the bird world—loud, energetic, and seemingly improvisational. Its song is a vast, chaotic, and joyful repertoire of paired phrases. A typical thrasher will sing a note or a short series of notes, immediately repeat it once, and then rapidly move on to a completely different sound and repeat that. It’s a continuous, long-winded performance that sounds like the bird is shouting, “Plant a seed, plant a seed, drop it now, drop it now, dig it up, dig it up!” They are incredible mimics, often incorporating snippets of other birds’ songs into their paired sequences, from Northern Cardinals to Carolina Wrens. The overall effect is less melodic and more declarative and exuberant than the Wood Thrush’s serene concerto.

Home Sweet Home: Preferred Habitat and Range

Where you see a bird is often the biggest clue to its identity. The brown thrasher vs wood thrush choice of real estate is a clear reflection of their different evolutionary paths and foraging strategies.

The Wood Thrush is a creature of the interior forest. It thrives in mature, deciduous, or mixed forests with a dense, moist understory and a thick layer of leaf litter on the ground. This is non-negotiable for their survival. They need these conditions for nesting and, most importantly, for foraging. They are rarely found in small urban parks or dry, open areas. They prefer large, contiguous tracts of woods, which makes them particularly vulnerable to habitat fragmentation. During migration, they can be found in similar wooded habitats, but their breeding grounds are tightly linked to these specific forest conditions across the eastern United States and southeastern Canada.

The Brown Thrasher is a bird of edges and openings. It prefers messy, tangled, scrubby areas. Think overgrown fields, hedgerows, forest edges, woodland clearings, and yes, the dense shrubbery and brush piles in your own backyard. They love areas with dense, thorny vegetation like blackberry bushes, multiflora rose, and honeysuckle, which provide excellent protection for their nests. They are much more adaptable to human-altered landscapes than the Wood Thrush, as long as there are sufficient thickets for cover. Their range covers the eastern half of the United States, and they are often year-round residents in the southeastern states, unlike the migratory Wood Thrush.

Table: Brown Thrasher vs Wood Thrush At a Glance

| Feature | Brown Thrasher | Wood Thrush |

|---|---|---|

| Family | Mimidae (Mimics) | Turdidae (True Thrushes) |

| Size & Shape | Large (11-12 in), slender, long tail | Smaller (7.5-8.5 in), compact, pot-bellied, shorter tail |

| Primary Color | Warm, rufous-brown above | Rich, reddish-brown on head and back |

| Underparts | White with heavy, dark brown streaks | White with large, distinct dark spots |

| Eye Color | Bright yellow | Dark brown |

| Bill | Long, slightly downcurved | Shorter, straight |

| Song | Long series of paired phrases; mimicry; chaotic | Short, flute-like, melodic phrases with echo; “ee-oh-lay” |

| Habitat | Brushy areas, forest edges, thickets, suburbs | Mature forest interior with dense understory |

| Foraging | Thrashes ground with bill in dirt/leaves | Delicately turns over leaves on forest floor |

| Migration | Short-distance or permanent resident | Long-distance migrant to Central America |

A Tale of Two Diets: Foraging and Feeding Behavior

How these two birds find their food is a fascinating display of adaptation. Their techniques are as different as their songs, perfectly suited to their respective habitats.

The Wood Thrush is a delicate forager of the forest floor. It moves with a graceful, deliberate hop through the leaf litter, pausing to cock its head to listen for and spot movement underneath. It then uses its bill to deftly flip over leaves to uncover hidden treasures beneath: beetles, spiders, earthworms, snails, and other invertebrates. Its feeding is quiet and methodical, a gentle rummaging rather than a violent excavation. During the late summer and fall, they will also supplement their diet with berries and fruits, such as spicebush, dogwood, and wild grapes, but protein-rich insects remain their primary food source, especially during the breeding season.

The Brown Thrasher lives up to its name. The word “thrasher” comes from its vigorous foraging technique. It uses its long, strong bill as a tool and a weapon. It will aggressively sweep, or “thrash,” its bill side-to-side through leaf litter, soil, and even under roots and rocks to uncover insects, grubs, and worms. This method is far more forceful and disruptive than the thrush’s technique. They are also omnivorous opportunists. While their diet is heavily insect-based in spring and summer, they readily eat a wide variety of berries, fruits, seeds, and even nuts. They will often forage in pairs or small family groups outside of the breeding season, and are known to visit platform feeders for seeds or suet, something a Wood Thrush would almost never do.

The Circle of Life: Nesting, Eggs, and Reproduction

The reproductive strategies of these birds further highlight their ecological differences, from nest location to the appearance of their eggs.

A Brown Thrasher’s nest is a well-concealed fortress. The pair typically builds its nest low to the ground, often less than five feet high, nestled deep within a tangled, impenetrable thicket of thorns and brambles. The nest itself is a bulky, messy-looking cup constructed from twigs, leaves, and rootlets, lined with softer materials like fine grasses. The female lays a clutch of 3-5 eggs that are a beautiful pale blue to greenish-blue, generously speckled with reddish-brown spots. This camouflage is essential for a nest built so vulnerably close to the ground. Both parents fiercely defend the nest against intruders, including much larger animals like cats and snakes, and they are known for their aggressive dive-bombing attacks.

The Wood Thrush, true to its nature, seeks a different kind of security. It builds its nest in the understory of the mature forest, but typically chooses a small tree or a horizontal branch, usually between 5 and 15 feet above the ground. They often select a fork in a tree, such as a dogwood or a red maple, using it as an anchor point. The nest is a beautiful, neat cup of mud, grass, and leaves, often lined with rootlets. The use of mud gives the nest structural integrity, a classic trait of many true thrushes (like the American Robin). The female lays a clutch of 3-4 eggs, which are a stunning, unmarked sky blue—a stark contrast to the thrasher’s heavily speckled eggs. The elevated, camouflaged location in the dappled forest light is their primary defense.

On the Move: Migration Patterns and Wintering Grounds

The annual journey each species undertakes is a major point of divergence in the brown thrasher vs wood thrush discussion and has significant implications for their conservation.

The Wood Thrush is a celebrated long-distance neotropical migrant. As summer wanes in North America, every Wood Thrush embarks on an incredible nocturnal journey, flying south to its wintering grounds in Central America, primarily from southern Mexico to Panama. This journey is fraught with perils, from storms and predators to collisions with human-made structures. Their dependence on two distinct habitats—breeding forests in the north and wintering forests in the south—makes them doubly vulnerable to habitat loss. Their population trends are closely monitored as an indicator of overall forest ecosystem health in the Americas.

The Brown Thrasher has a much more flexible approach. Populations in the deep South are largely permanent residents, staying on their territories year-round. Those that breed in the northern parts of their range (the Upper Midwest, Great Lakes, and New England) are short-distance migrants. They simply move southward within the United States to escape the harshest winter weather, often settling in areas throughout the southeastern states. They do not undertake the perilous trans-oceanic or trans-gulf migration that the Wood Thrush must face. This adaptability gives them a conservation advantage, as they are less affected by the destruction of tropical wintering habitats.

Conservation Status: How Are They Faring?

Understanding the population health of these species helps us appreciate the broader environmental challenges they face.

The Wood Thrush is a species of significant conservation concern. According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, its populations have experienced a steady and concerning decline—approximately 60% since 1966. The primary culprits are well-known: habitat fragmentation and destruction on both its breeding grounds in North America and its wintering grounds in Central America. The increase of nest parasites like Brown-headed Cowbirds, which thrive in edge habitats, also takes a heavy toll on their reproductive success. When forests are broken up into smaller patches, cowbirds can access thrush nests more easily, and nest predators like raccoons and jays become more abundant. Protecting large, contiguous tracts of mature forest is the single most important action for Wood Thrush survival.

The Brown Thrasher, while still common, is also experiencing population declines, though they are less severe than those of the Wood Thrush. Their decline is largely attributed to habitat loss on their breeding territories. The “cleaning up” of landscapes—the removal of fencerows, fallow fields, and scrubby, overgrown areas in favor of intensive agriculture or manicured lawns—has eliminated the messy habitats they depend on. Their adaptability to human presence is a double-edged sword; while they can live in suburbs, they still require dense, native shrubs for nesting and cover, which are often replaced by non-native ornamentals that don’t support the insects they need to feed their young.

Silkie Rooster vs Hen: Your Ultimate Guide to Telling Them Apart

Beyond the Binoculars: Cultural Significance and Fun Facts

These birds have not only captured the attention of scientists and birders but have also fluttered into our art, literature, and collective imagination.

The song of the Wood Thrush has been described by numerous naturalists and writers as one of the most sublime natural sounds. Henry David Thoreau wrote extensively about it in his journals, captivated by its beauty. Its flute-like melody is often used in film and television soundscapes to instantly evoke a sense of pristine wilderness and tranquility. For many, the song is a nostalgic reminder of deep, eastern forests and is a symbol of wildness and the magic of the natural world that persists even as it changes around us.

The Brown Thrasher, though less romanticized, holds its own unique honors. It is the official state bird of Georgia, a testament to its prevalence and character in the Southeast. Its scientific name, Toxostoma rufum, literally means “red bow-mouth,” a reference to its curved bill and rufous color. Furthermore, the Brown Thrasher holds the Guinness World Record for the bird with the largest song repertoire! A single bird can know over 1,100 different song types, though they typically use a repertoire of about 1,000 to 2,000 in their local area. This incredible vocal prowess showcases the intelligence and complexity of the mimic family.

Quotes from the Experts

“The Wood Thrush is the only bird whose song has ever seemed to me to be the perfect expression and interpretation of the deep calm and holy peace of the wilderness.” – John Burroughs, Naturalist and Essayist

“The Brown Thrasher is a handsome, spirited bird, and a singer of exceptional ability… His song is a wild, free outburst, a medley of his own and borrowed notes, delivered with great force and enthusiasm.” – Arthur Cleveland Bent, Ornithologist and Author

Conclusion

The journey to distinguish a brown thrasher vs wood thrush is more than just an exercise in identification; it’s a lesson in ecology, adaptation, and appreciation. While they may share a similar color palette, these two birds are masterpieces of divergent evolution. The Wood Thrush, the serene flutist of the deep forest interior, reminds us of the fragile beauty of wilderness and the urgent need for conservation. The Brown Thrasher, the exuberant mimic of the tangled thicket, teaches us about adaptability, intelligence, and the value of “messy” nature right in our backyards.

The next time you hear a beautiful song in the eastern woods or fields, you’ll be equipped to listen more deeply and look more closely. You’ll know to scan the forest floor for a spotted, pot-bellied thrush or to peer into the brambles for a streaked, long-tailed thrasher. Each bird, in its own unique way, adds a rich layer to the tapestry of our natural world. By understanding their differences, we can become better stewards of the specific habitats they need to thrive, ensuring that the thrasher’s joyful ramble and the thrush’s ethereal flute continue to grace our landscapes for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main difference between a Brown Thrasher and a Wood Thrush?

The most immediate difference is their song and their breast pattern. The Wood Thrush has a flute-like, melodic song and a white breast with distinct black spots. The Brown Thrasher has a loud, chaotic song of paired phrases and a white breast with heavy, dark brown streaks. Taxonomically, they belong to different families: thrushes (Turdidae) vs. mimics (Mimidae).

Can a Brown Thrasher mimic a Wood Thrush?

Yes, absolutely. As a member of the mimic family, the Brown Thrasher is an accomplished vocal copycat and can incorporate snippets of the Wood Thrush’s song into its own vast repertoire. However, it will always deliver these mimicked phrases in its characteristic style, usually repeating each phrase twice before moving on to a new sound, which helps birders tell the difference.

Which bird is more likely to visit my backyard?

The Brown Thrasher is far more likely to be a backyard visitor. They are attracted to properties with dense shrubbery, brush piles, and overgrown edges where they can nest and forage. They may even visit platform feeders for seeds or suet. The Wood Thrush is a bird of deep forest interior and is very unlikely to visit a typical suburban backyard unless it borders a large, mature woodland.

Are both the Brown Thrasher and Wood Thrush migratory?

Their migration strategies differ significantly. The Wood Thrush is a complete long-distance migrant, traveling to Central America for the winter. The Brown Thrasher is often a permanent resident in the southeastern U.S., while northern populations only migrate short distances within the United States, making them less vulnerable to the dangers of long-distance travel.

Why is the Wood Thrush population declining?

The Wood Thrush faces severe threats from habitat fragmentation and loss on both its breeding grounds in North America and its wintering grounds in Central America. The breaking up of large forests into smaller patches increases their exposure to nest predators and brood parasites like Brown-headed Cowbirds. Protecting large, contiguous tracts of mature deciduous forest is critical for their survival.