You see a long-eared animal in a field, and the question pops into your head: Is that a donkey or a mule? You’re not alone. For centuries, these hardy creatures have been pillars of human agriculture and transportation, yet their distinctions often blur into confusion. While they share a family tree and a distinct silhouette, the differences between a mule and a donkey are profound, spanning genetics, physicality, temperament, and purpose. Understanding the “mule vs donkey” debate is more than just trivia; it’s a journey into the fascinating world of equine hybridization and selective breeding. This article will be your definitive guide, peeling back the layers to reveal what makes each of these animals uniquely exceptional. We’ll explore everything from their fundamental DNA to their quirky personalities, helping you become an expert in telling them apart and appreciating their individual strengths.

The confusion is understandable. At a glance, both animals boast those iconic long ears, a signature feature they inherit from the donkey side of the family. But once you know what to look for, the differences become as clear as day. This isn’t just about identifying animals; it’s about understanding a remarkable success story of human ingenuity. The mule, a hybrid creature, represents a deliberate attempt to combine the best qualities of two separate species: the sturdy, patient donkey and the powerful, swift horse. The result is an animal that has, in many ways, surpassed both its parents in terms of endurance and resilience for specific tasks. So, whether you’re a potential owner, an equine enthusiast, or simply curious, join us as we delve deep into the world of these incredible animals.

Defining the Donkey: The Sturdy Ancestor

Before we can fully appreciate the mule, we must first understand its direct parent, the donkey. Known scientifically as Equus africanus asinus, the donkey is a species in its own right, domesticated from the African wild ass around 5,000 years ago. Donkeys have been humanity’s loyal companions for millennia, primarily valued for their ability to thrive in harsh, arid environments where horses might struggle. They are the original pack animals, capable of carrying heavy loads across difficult terrain with a calm and steady demeanor. Their reputation for stubbornness is largely a misunderstanding; a donkey’s hesitation is often a display of a strong survival instinct and a keen sense of self-preservation, pausing to assess a potentially dangerous situation rather than blindly charging forward.

Physically, donkeys have a very distinct build. They are generally smaller than horses, with a straight back, a narrow chest, and a large head that seems perfectly proportioned for those magnificent ears. Those ears aren’t just for show; they provide an exceptional sense of hearing, allowing the donkey to detect predators from a great distance. Their mane is stiff and upright, rarely lying flat like a horse’s mane, and their tail resembles a cow’s tail, with a tuft of hair only at the end, unlike the horse’s full tail. Their coat is often a shade of gray-dun, but they can also be black, brown, white, or even spotted. Most notably, many donkeys sport a “cross” on their back—a dark stripe that runs down the spine and across the shoulders—a trait believed to be a remnant of their wild ancestry. This unique combination of traits makes the donkey perfectly adapted to a life of hard work in challenging climates.

Defining the Mule: The Powerful Hybrid

Now, let’s turn our attention to the mule, the fascinating outcome of crossbreeding. A mule is not a species but a hybrid, the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). This specific parentage is crucial because the reverse pairing—a male horse (a stallion) and a female donkey (a jenny)—produces a different hybrid called a hinny, which is less common and has subtle differences we will touch on later. The mule is a testament to hybrid vigor, a biological phenomenon where the crossbred offspring exhibits qualities superior to either parent. For centuries, humans have intentionally bred mules to create an animal that combines the strength, size, and speed of the horse with the patience, endurance, intelligence, and sure-footedness of the donkey.

When you look at a mule, you see a blend of both parents. It typically has the body shape of a horse, but is distinguished by the donkey-like ears, though they are often slightly less elongated than a pure donkey’s. Its legs are straighter and more horse-like, and its hooves are tougher and more upright than a horse’s, requiring less frequent shoeing. The mule’s tail is a full horse tail, which is a key visual differentiator from the donkey’s tufted tail. Mules inherit a combination of their parents’ coats and can be found in virtually any color that horses or donkeys come in. Perhaps the most significant characteristic of the mule, and a central point in the “mule vs donkey” discussion, is its sterility. Due to an odd number of chromosomes (63, compared to the horse’s 64 and the donkey’s 62), mules are almost always unable to reproduce. This genetic dead-end means every mule is a unique creation, deliberately bred for a purpose.

The Fundamental Genetic Difference

The core of the “mule vs donkey” distinction lies in their genetics, which dictates every other difference we observe. A donkey is a pure species with 62 chromosomes. These chromosomes pair up perfectly during reproduction, allowing for the creation of fertile offspring. A horse, on the other hand, has 64 chromosomes. When a jack donkey mates with a mare horse, the resulting mule ends up with 63 chromosomes—an uneven number that is half-way between its parents. This odd number is the reason for the mule’s celebrated hybrid vigor, but it is also the cause of its infertility.

During the process of meiosis (the creation of sperm and egg cells), chromosomes need to pair up neatly. With an odd number, this pairing is chaotic and incomplete, meaning mules cannot produce viable gametes. This sterility is a natural biological barrier that prevents the blending of species in the wild. It also means that mules must be intentionally bred by humans; you will never find a wild population of mules. The hinny, the offspring of a stallion and a jenny, also has 63 chromosomes and is also sterile. While the mule and hinny are both equine hybrids, the mule is far more common and generally preferred because the larger size of the mare’s womb tends to produce a larger, stronger animal than the jenny’s smaller womb. This genetic lottery is the fundamental reality that separates the reproducible donkey species from the one-of-a-kind mule hybrid.

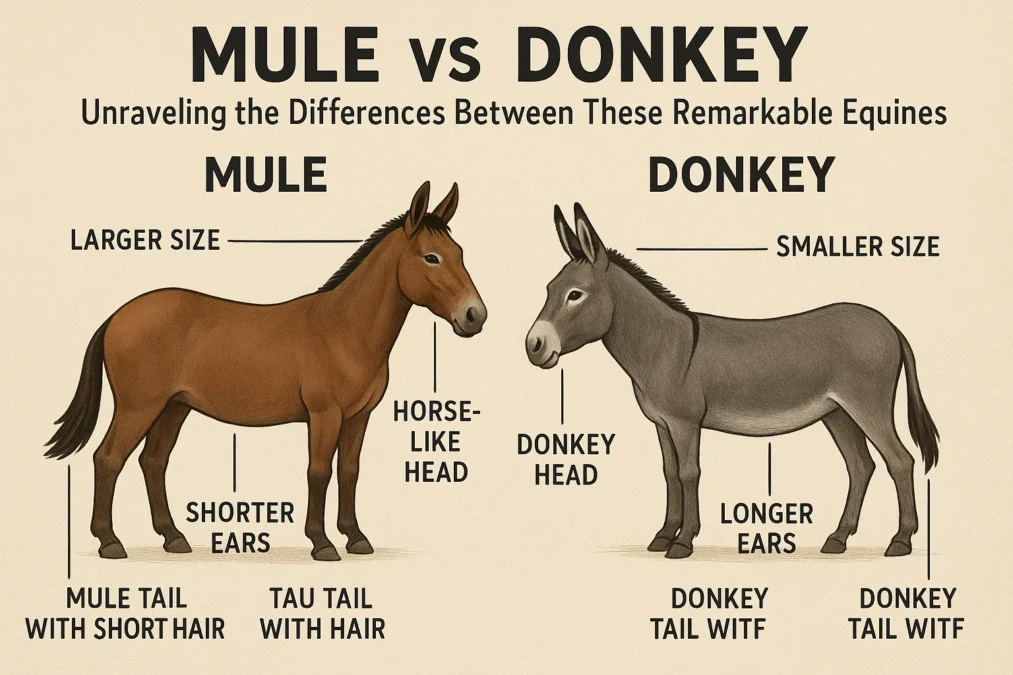

Physical Characteristics: A Side-by-Side Comparison

When comparing a mule and a donkey side-by-side, the physical differences become apparent, even to the untrained eye. Let’s break down the key areas of comparison.

Starting with size, donkeys vary greatly, from miniature breeds standing under 36 inches to large mammoth jacks that can reach over 56 inches at the shoulders. However, the standard donkey is generally smaller than a typical mule. A mule, having a horse for a mother, almost always grows larger than a donkey, often matching or exceeding the size of the mare it came from. Its build is more robust and muscular, inheriting the horse’s power while retaining the donkey’s leaner bone structure, which is often denser and stronger than a horse’s. The head is a clear indicator: a donkey has a large, broad forehead and a straight profile, while a mule’s head is more refined, looking closer to a horse’s but with the unmistakably long ears of the donkey, though these ears are usually proportional to its larger head.

The body and extremities also tell a story. A donkey has a straight back, a narrow chest, and a sloped croup. Its hooves are smaller and more upright, an adaptation for rocky ground. A mule’s body is more horse-like: a curved neck, a wider chest, and a well-muscled back and hindquarters. Its hooves are tougher than a horse’s but larger and less vertical than a donkey’s. The voice is another dead giveaway. A donkey produces the famous “hee-haw,” a loud, braying sound that can carry for miles. A mule can bray like a donkey, but it often also whinnies like a horse, and sometimes produces a unique, comical-sounding combination of the two. Finally, the tail is one of the easiest markers: a donkey’s tail has a short tuft of hair at the end, like a cow, while a mule sports the long, flowing, full-haired tail of its horse mother.

Temperament and Behavior: Stubbornness vs. Intelligence

The behavioral differences between mules and donkeys are where the “mule vs donkey” debate gets really interesting, and where misconceptions abound. Donkeys are often labeled as stubborn. This is a gross oversimplification of their highly developed sense of self-preservation. Donkeys are thinkers. In the wild, their ancestors lived in precarious environments where a wrong step could be fatal. As a result, donkeys are naturally cautious. They will stop and assess a situation they perceive as dangerous. This isn’t defiance; it’s intelligence. Once a donkey trusts its handler, it is incredibly loyal, patient, and gentle. They form deep bonds and can be wonderfully affectionate companions.

Mules inherit this donkey intelligence but often temper it with a bit more of the horse’s willingness to please. They are renowned for being incredibly smart, perhaps even smarter than either parent. A mule learns quickly, remembers everything, and is very difficult to force into doing something it considers unsafe. This is why the saying goes, “You can ask a horse, but you must tell a mule.” A horse might be trained to obey commands without question, but a mule requires a partnership based on mutual respect and trust. If a mule senses incompetence or fear in its rider, it will simply refuse to cooperate. In the hands of a skilled and patient handler, however, a mule is an unparalleled worker—willing, dependable, and capable of making good decisions on its own. This combination of horse-like athleticism and donkey-like cunning makes the mule exceptionally sure-footed and reliable in treacherous conditions, which is why they have been the preferred pack animal for mountain military units for centuries.

Strengths and Weaknesses in Work and Performance

The different temperaments and physical attributes of mules and donkeys make them suited for different types of work. Understanding their strengths and weaknesses is key to appreciating their respective roles.

Donkeys excel as guardians and steady workers. Their protective instinct is so strong that they are often used as “livestock guardian animals” to protect herds of sheep, goats, and even cattle from predators like coyotes and dogs. A donkey will bravely confront a threat, using its powerful kick and bite to defend its herd. As working animals, donkeys are ideal for tasks that require a slow, steady pace. They are phenomenal pack animals for trail riding or carrying loads on a farm. Their efficient metabolism and ability to thrive on poorer forage make them cheaper to keep than horses or mules. However, their smaller size and cautious nature mean they are not well-suited for high-speed activities like riding sports or pulling heavy plows at a fast pace. Their greatest strength is their unwavering reliability in the jobs they know and understand.

Mules, on the other hand, are the ultimate all-terrain performance vehicles of the equine world. They combine the strength to pull heavy loads or carry heavy riders with the endurance to do it for long distances. Their skin is thicker than a horse’s, making them more resistant to saddle sores and weather extremes. They are incredibly sure-footed, making them the first choice for trail riding, packing, and working in mountainous or rocky landscapes. Mules are also famous for their “wind,” meaning they have exceptional cardiovascular endurance and are less prone to overheating or exhaustion than horses. The primary weakness of a mule is not physical but managerial: their high intelligence requires a skilled and confident handler. They are not an ideal choice for a novice equestrian. Furthermore, because of their hybrid nature, they can be more expensive to purchase than a donkey or a horse of comparable training. But for the right person, a mule’s working capacity is virtually unmatched.

Brown Thrasher vs Wood Thrush: The Ultimate Birdwatcher’s Guide

The Hinny: The Other Equine Hybrid

In any discussion of “mule vs donkey,” it’s important to acknowledge the often-forgotten cousin: the hinny. A hinny is the reciprocal cross of a mule, the offspring of a male horse (stallion) and a female donkey (jenny). Genetically, a hinny also has 63 chromosomes and is sterile, just like a mule. So, what’s the difference? The difference lies in the maternal influence. The mother contributes not only half the chromosomes but also the prenatal environment, including the size of the womb and the hormonal influences during pregnancy.

A mule, born from a horse mare, benefits from a larger womb and more nutrient-rich gestation, which generally results in a larger, more robust animal. A hinny, born from a smaller jenny donkey, has a more constrained prenatal environment and tends to be smaller, often closer in size to a donkey. Physically, hinnies can be harder to distinguish from donkeys because they may exhibit more donkey-like characteristics, such as a smaller head and ears that are only slightly longer than a horse’s. They are also much rarer than mules, partly because the crossbreeding is less successful and partly because the resulting animal is typically smaller and less powerful than a mule, making it less desirable for work. The hinny serves as a fascinating reminder that in the world of hybridization, the mother’s contribution is profoundly impactful on the final outcome.

Historical and Cultural Significance

The stories of the donkey and the mule are deeply woven into the fabric of human history. The donkey’s history is one of humble service. It was the beast of burden that enabled trade routes across Africa and Asia, carried families to new lands, and worked tirelessly on small farms around the world. It is a symbol of patience, humility, and perseverance in many cultures. In the Christian tradition, the donkey is honored for carrying Mary to Bethlehem and Jesus into Jerusalem. Despite its crucial role, it has often been seen as a low-status animal, a perception that belies its incredible toughness and contribution to civilization.

The mule’s history is one of engineered excellence. The ancient Greeks and Romans recognized the superior qualities of mules and bred them extensively for use in their armies and for pulling carts and plows. Mules were indispensable in the Age of Exploration and the colonization of the Americas, where they worked in mines, on plantations, and on pioneer trails. They were the engines of industry before the industrial revolution. In the United States, George Washington was a key figure in the development of the American mule population, recognizing their potential for the young nation’s agriculture. Mules played a critical role in the Civil War, pulling supply wagons and artillery, and they were the essential partners of prospectors during the Gold Rush. Their cultural image is one of rugged reliability and unassuming strength, a testament to human ingenuity in animal husbandry.

Choosing Between a Mule and a Donkey

So, when it comes down to making a choice between a mule and a donkey, the decision should be based on your specific needs, experience, and environment. If you are looking for a pet, a guardian for your livestock, or a calm, steady pack animal for light to moderate work on a small property, a donkey may be the perfect fit. Donkeys are generally easier for a novice to manage, require less feed, and their smaller size can be less intimidating. They are incredibly affectionate and form deep bonds with their owners and other animals. Their cautious nature can be a benefit in situations where a more impulsive horse or mule might get into trouble.

If you are an experienced equestrian looking for a partner for trail riding, competitive packing, ranch work, or any activity that requires strength, endurance, and agility over challenging terrain, a mule is likely the superior choice. A mule will offer you a level of performance and durability that is hard to match. However, you must be prepared to engage in a partnership, not a dictatorship. Mules require a handler who is confident, consistent, and respectful of their intelligence. They need more space, more high-quality feed, and more sophisticated training than a donkey. The choice isn’t about which animal is better overall, but which one is better for you. Assessing your own skills, goals, and resources is the first step in making the right decision.

Common Misconceptions and Myths

The world of equines is rife with myths, and the “mule vs donkey” topic has its fair share. The most pervasive myth is that donkeys are stupid and stubborn. As we’ve discussed, their “stubbornness” is actually a highly evolved survival instinct. A donkey that refuses to cross a unstable bridge isn’t being difficult; it’s being smart. They are highly intelligent animals that simply require patient and understanding handling. Another common misconception is that mules are always mean or dangerous. This is also untrue. A poorly treated mule can become defensive and difficult, but a mule raised with kindness and clear boundaries is one of the most good-natured and trustworthy animals you can find.

A related myth is that mules are always superior to donkeys. This is not the case; they are just different. For a person with limited equine experience or a need for a small, low-maintenance guardian animal, a donkey is unequivocally superior. The idea of “better” is entirely context-dependent. Finally, there is a myth that all mules and donkeys are cheap to keep because they are “tough.” While it’s true they are more efficient with feed and hardier than horses, they still require high-quality nutrition, regular hoof care, dental check-ups, and veterinary attention. Assuming otherwise is a disservice to these hardworking animals. Dispelling these myths is crucial for appreciating both the donkey and the mule for the remarkable creatures they are.

Care and Maintenance

While donkeys and mules share some basic care requirements with horses, they have unique needs that must be met to keep them healthy and happy. Both animals require shelter from the elements, constant access to fresh water, and a diet based on forage, such as grass or hay. However, donkeys and mules are more prone to obesity and metabolic issues like laminitis than horses are. Their efficient metabolism, a blessing in harsh environments, becomes a curse when they are fed rich grasses or high-grain diets. Their diet must be carefully managed, often requiring lower-quality hay and restricted access to lush pasture.

Hoof care is essential for both. Donkeys’ hooves are more upright and may require less frequent trimming than a horse’s, but they are not “self-maintaining.” Mules’ hooves are famously tough and durable, but they still grow and need regular trimming by a farrier familiar with equine hybrids. One significant difference in care is their response to weather. Donkeys, originating from arid climates, have coats that are not as waterproof as a horse’s. They require a dry shelter to escape rain and snow, as a wet donkey can become chilled quickly. Mules share this need for shelter. Both animals are highly social and can suffer from loneliness if kept alone; they thrive best with the company of another donkey, mule, goat, or other compatible animal. Understanding and meeting these specific care requirements is the foundation of responsible ownership.

A Visual Comparison Table

| Feature | Donkey | Mule |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Origin | Pure species (Equus africanus asinus) | Hybrid (Jack donkey x Mare horse) |

| Chromosomes | 62 | 63 (Sterile) |

| Size & Build | Generally smaller; straight back, narrow chest. | Generally larger; horse-like body, muscular. |

| Ears | Very long, a defining feature. | Long, but often proportional to its larger head. |

| Tail | Short hair with a tuft at the end (cow-like). | Long, full hair from the dock (horse-like). |

| Voice | Loud, distinctive “Hee-Haw” bray. | A mix: can bray, whinny, or a combination. |

| Temperament | Cautious, intelligent, strong self-preservation. | Highly intelligent, requires trust-based training. |

| Primary Strengths | Guardian animal, steady pack animal, hardy. | Endurance, strength, sure-footedness. |

| Ideal For | Novice owners, livestock protection, light work. | Experienced handlers, trail riding, heavy work. |

Voices from the Past and Present

“The mule is an animal of surprising strength, patience, and perseverance. He will travel from twenty to thirty miles a day, for a week together, with a heavy burden on his back, and upon a scanty allowance of food.” – John C. Frémont, 19th-century American explorer.

“The donkey is the silent partner in the history of civilization, bearing its burdens without complaint and asking for little in return.” – A common sentiment among donkey enthusiasts.

“A mule will not stumble over the same stone twice. A horse might, and a donkey will sit down and think about it for a week, but a mule learns the first time.” – An old rancher’s saying.

Conclusion

The journey through the world of “mule vs donkey” reveals a story not of competition, but of complementarity. The donkey stands as a testament to the power of a species perfectly adapted to survival, offering unwavering loyalty and steady service. The mule represents the pinnacle of human-driven hybrid vigor, a creature crafted to embody the finest attributes of both the horse and the donkey. One is a purebred survivor, the other a masterful blend. The choice between them is not about finding a winner, but about matching the right animal to the right task and the right person. By understanding their profound genetic, physical, and behavioral differences, we can move beyond simplistic labels and appreciate both the donkey and the mule for the intelligent, capable, and historically vital equines they truly are. Whether it’s the humble bray of a donkey guarding a flock or the sturdy silhouette of a mule carrying a pack deep into the wilderness, each has earned its place as an indispensable partner to humanity.

Frequently Asked Questions About Mule vs Donkey

What is the main biological difference between a mule and a donkey?

The main biological difference is that a donkey is a distinct species with 62 chromosomes, capable of reproducing. A mule, however, is a sterile hybrid resulting from crossing a male donkey with a female horse. It inherits 63 chromosomes, an uneven number that prevents it from producing viable sperm or eggs. This fundamental genetic distinction is the root of all other differences between the two.

Can a mule ever have babies?

It is extraordinarily rare, but not entirely impossible. There are a handful of documented cases in history where a female mule has produced a foal. These events are considered biological anomalies and are the exception that proves the rule. For all practical purposes, when discussing mule vs donkey reproduction, you should assume that every mule you encounter is sterile and cannot have offspring.

Why are mules considered smarter than horses?

Mules are often considered smarter because they inherit the strong self-preservation instinct and cautious intelligence of the donkey, combined with the horse’s physical capabilities. This results in an animal that learns quickly, remembers experiences (both good and bad), and is less likely to blindly obey a command that it perceives as dangerous. This analytical nature is interpreted as a higher form of intelligence, especially in working situations where judgment is critical.

Is a donkey or a mule better for a first-time owner?

For a first-time equine owner, a donkey is generally a better choice than a mule. Donkeys are typically smaller, less intimidating, and their cautious nature can be safer for an inexperienced handler. They are also less prone to panic. A mule’s high intelligence requires a confident and knowledgeable handler who understands how to build a partnership based on respect rather than force, which can be challenging for a novice.

What is the difference between a mule and a hinny?

The difference between a mule and a hinny lies in their parentage. A mule is the offspring of a male donkey (jack) and a female horse (mare). A hinny is the offspring of a male horse (stallion) and a female donkey (jenny). While both are hybrids with 63 chromosomes, a mule is usually larger and more horse-like because it gestates in a mare’s larger womb. Hinnies are rarer and often smaller, with features that can more closely resemble a donkey.