Pin Nailer vs Brad Nailer: Walking into the world of pneumatic or battery-powered nailers is an exciting step for any DIY enthusiast or professional woodworker. It opens up a realm of precision, speed, and clean finishes that a hammer and nails simply can’t match. But with this new world comes a crucial question that has puzzled many a craftsperson: what exactly is the difference between a pin nailer and a brad nailer? They look similar, they sound similar, and to the untrained eye, they seem to do the same job. This common misconception can lead to frustrating project failures, from split wood to insecure joints.

The truth is, while these two tools are cousins in the family of finish nailers, they are designed for distinctly different missions. Choosing the wrong one is like using a scalpel to chop down a tree—it’s not just ineffective, it can ruin your tools and your materials. Understanding the “why” behind each tool’s design is the key to unlocking professional-level results in your own work. This comprehensive guide is designed to be your definitive resource. We will dive deep into the anatomy, strengths, and weaknesses of both the pin nailer and the brad nailer, moving beyond the basic specs to the practical, hands-on knowledge you need. We’ll explore scenarios where one is unequivocally the champion, and others where the choice is less clear, ensuring you can approach your next project with complete confidence.

Getting to Know the Brad Nailer: The Versatile Workhorse

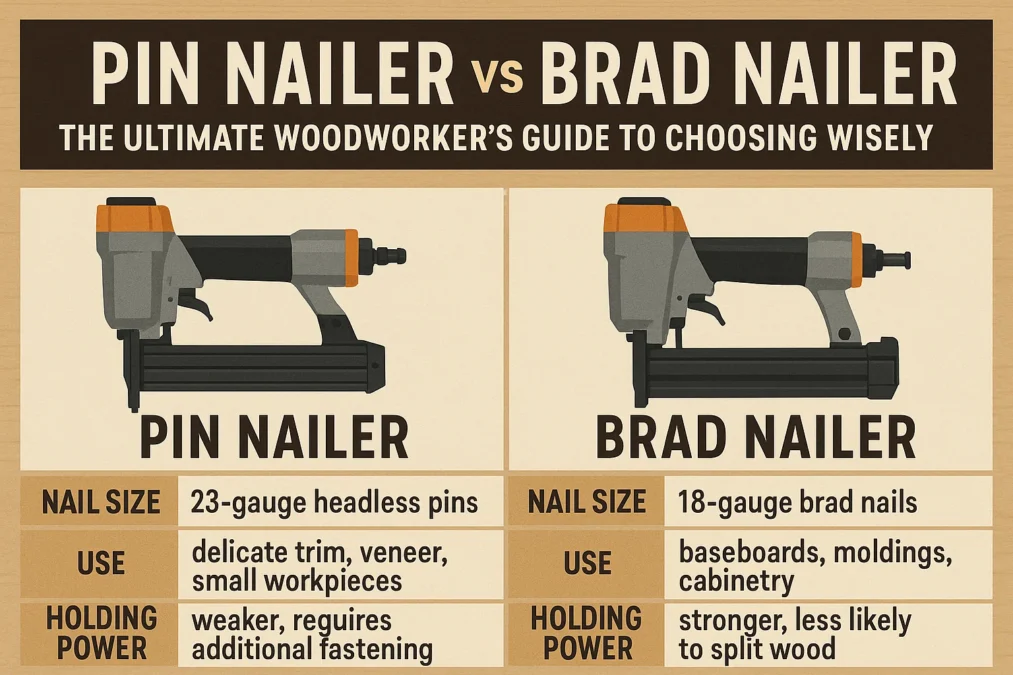

Let’s start with the tool you’re more likely to encounter first: the brad nailer. Think of the brad nailer as the reliable all-rounder in your workshop, the tool that handles a surprisingly wide array of tasks with grace and efficiency. Brad nailers are designed to fire brad nails, which are essentially small, thin, finished nails. The key characteristic of a brad nail is that it has a very small, T-shaped head. This head is large enough to provide a modicum of holding power, but small enough that it can be easily driven just below the surface of the wood without leaving a massive crater. A quick application of wood filler makes the fastener virtually disappear.

The gauge of a brad nailer is typically 18-gauge. For those unfamiliar with wire gauge, the important thing to remember is that the higher the number, the thinner the nail. So, an 18-gauge nail is thinner than a 16-gauge finish nail but thicker than the pin nails we’ll discuss next. Brad nails commonly range in length from about 5/8 of an inch up to 2 inches, giving you a good range for everything from delicate trim to assembling small boxes. This combination of a small head and a thin-but-not-too-thin body makes the brad nailer incredibly versatile.

The Ideal Use Cases for a Brad Nailer

The brad nailer truly shines in applications where you need a blend of discreet fastening and genuine holding strength. Its most common and celebrated use is in installing trim and molding. Crown molding, baseboards, window and door casings—all of these are perfect jobs for a brad nailer. The nail is strong enough to hold the trim securely against the wall, even if there’s a slight warp, but the head is small enough that the hole is easy to conceal. It provides significantly more holding power than a pin nailer, making it a safer bet for trim that might experience incidental contact. Furthermore, the thinner gauge compared to a 16-gauge nail means it’s far less likely to split the often-delicate edges of wooden moldings.

Another fantastic application for the brad nailer is in light woodworking and assembly. Think picture frames, small jewelry boxes, cabinet face frames, and attaching plywood backs to furniture. In these scenarios, the brad nailer acts as a quick and effective clamp while your wood glue dries. The nails hold everything in perfect alignment, and because they are thin, they won’t compromise the integrity of the wood or distract from the final appearance. It’s also the preferred tool for attaching thinner paneling, applying decorative accents, and any task where you need more finesse than a finish nailer offers but more muscle than a pin nailer can provide.

The Limitations of the Brad Nailer

For all its versatility, the brad nailer is not a magic bullet. Its primary limitation stems directly from its design: that small head. While great for minimizing visibility, it does not provide the same tenacious grip as a full-headed nail. This means that a brad nailer should never be used for structural applications. If you’re building a bookshelf that needs to support weight, the joints should be properly joined with woodworking techniques like dados, dowels, or pocket screws, with the brad nails merely serving as supplemental reinforcement or for attaching non-structural elements.

The other notable limitation is that, despite its thin gauge, it can still split very hard or exceptionally brittle woods, especially when nailing close to an end grain. While the risk is lower than with a 16-gauge nail, it’s not zero. Using a dull driver blade in the tool can also exacerbate this issue, as it may crush the wood fibers rather than cleanly pushing the nail through. Finally, on some ultra-delicate projects or with certain types of veneers, even the small hole left by an 18-gauge brad can be considered too large, creating a finishing challenge that a different tool might avoid altogether.

Delving into the Pin Nailer: The Master of Discretion

If the brad nailer is the versatile workhorse, then the pin nailer is the stealthy specialist, the master of invisible fastening. A pin nailer drives headless pins, which are essentially just small, straight lengths of hardened steel. Yes, you read that correctly—they have no head whatsoever. This is the single most defining characteristic of the tool and the source of both its greatest strengths and its most significant weaknesses. These pins are even thinner than brad nails, typically coming in at 23-gauge, which is the smallest and finest gauge commonly available in the nailer world.

Pin nails are shorter as well, usually ranging from a tiny 1/2 inch to a maximum of 1 and 3/8 inches or, in some specialty models, 2 inches. Because they lack a head, they do not provide any clamping force or mechanical grip on the surface of the material. Their sole purpose is to hold two pieces of material together, acting almost exclusively as a locator or a temporary hold while a much stronger adhesive, like wood glue, cures. When driven properly, a pin nail leaves a hole so minuscule that it often closes up on its own or requires only a drop of water or a quick sanding to disappear completely.

Where the Pin Nailer is Absolutely Unbeatable

The pin nailer’s claim to fame is in the realm of ultra-fine woodworking and applications where any visible fastener hole is completely unacceptable. Its most classic use is in attaching delicate decorative trim, intricate moldings, and small inlays. When working with fragile ogee details or tiny pieces of appliqué, even an 18-gauge brad nail has a high risk of splitting the material. The 23-gauge pin exerts so little pressure that it can secure the most delicate pieces without a hint of damage. This makes it indispensable for high-end furniture makers and cabinet makers who work with expensive, brittle hardwoods.

Another superpower of the pin nailer is its utility in temporary tacking and complex glue-ups. When assembling a complicated piece with multiple parts, you can use pin nails to hold everything in perfect alignment while the glue sets. Since the holes are nearly invisible, you don’t have to worry about filling unsightly holes later. It’s also the ultimate tool for working with veneers and thin plywoods. A brad nailer could easily blow right through the side of a piece of veneer, but a pin nailer can secure it cleanly and discreetly. For attaching beadboard panels, securing the delicate corners of a shadow box, or any task where the finish is paramount, the pin nailer is the only correct choice.

Understanding the Drawbacks of a Pin Nailer

The drawbacks of the pin nailer are direct consequences of its headless, thin design. The most significant limitation is its lack of holding power. A pin nailer should never be used as the sole method of fastening for anything that requires mechanical strength. It provides almost zero resistance to pulling forces. If you try to use it to hang a picture frame or secure a piece of baseboard without glue, you will be sorely disappointed when it falls off the wall. It is purely an adhesive assistant and a positioning tool, not a fastener in the traditional, load-bearing sense.

The other main drawback is its limited reach and penetration depth. Because the pins are so thin and lack a head to be driven by the tool’s mechanism, they can sometimes have trouble penetrating very hard woods. They can also deflect more easily than a brad nail if you don’t hold the tool perfectly square to the work surface. Their short length also means they are unsuitable for attaching thicker materials. You would never use a pin nailer to build a fence or assemble a 2×4 frame; it simply doesn’t have the substance for such tasks. It is a specialist tool for the final, most delicate stages of a project.

Head-to-Head: A Detailed Feature Comparison

To truly grasp the difference between a pin nailer and a brad nailer, it’s helpful to break down their characteristics side-by-side. This goes beyond just nail size and delves into the practical implications for your workflow and your final product. Understanding these core differences will move you from simply knowing the specs to intuitively understanding which tool to grab for any given task. The choice often comes down to a simple trade-off: strength versus stealth. The brad nailer brings more holding power to the table, while the pin nailer offers an unparalleled invisible finish.

One of the most critical comparisons lies in the fastener itself. The brad nail, with its 18-gauge thickness and small head, is designed to be a genuine fastener that also happens to be discreet. The pin nail, a 23-gauge headless pin, is designed to be invisible first and a fastener a distant second. This fundamental difference in philosophy dictates every aspect of their use. The brad nail’s head allows the tool’s driver blade to impart significant force, pushing the nail deep and drawing the materials together slightly. The pin nail, with no head, is simply pushed into place, offering no clamping action.

Comparing Holding Power and Fastener Strength

When it comes to raw holding power, there is no contest; the brad nailer is the clear winner. The 18-gauge nail, coupled with its small head, provides a meaningful amount of resistance to being pulled out. It can securely hold moldings in place, assemble small projects, and provide lasting strength when paired with glue. This makes it a more versatile and forgiving tool for the average user. If you’re only going to own one fine-gauge nailer, the brad nailer is almost always the recommended choice because it can handle a broader spectrum of tasks effectively.

The pin nailer, in contrast, offers minimal independent holding power. Its strength is almost entirely dependent on the bond of the wood glue you are using. The pin’s job is merely to keep the pieces from sliding apart while the glue cures, not to provide any long-term structural integrity. If you attempt to use pin nails alone on a project like a cabinet door, the joints will inevitably fail over time as wood expands and contracts with changes in humidity. This is not a flaw in the tool, but rather a reflection of its specific, glue-dependent purpose.

Stun Gun vs Taser: The Ultimate Guide to Choosing Your Self-Defense Tool

Assessing Visibility and the Finishing Process

In the arena of visibility and finish, the roles are reversed, and the pin nailer takes the crown. The hole left by a 23-gauge pin is phenomenally small. In many cases, especially with softer woods, the wood fibers will simply spring back after the pin is driven, closing the hole entirely. Even when a small hole remains, it can often be erased with a light sanding or a drop of water to swell the fibers. This leads to a truly flawless, factory-perfect finish that is incredibly difficult to achieve with any other fastening method.

The brad nailer, while still very discreet, leaves a more noticeable hole. The small T-shaped head must be set slightly below the surface, which creates a small divot that requires filling. While wood filler does an excellent job, it can sometimes be visible, especially if you are staining the wood rather than painting it. Matching the color and grain of the wood with filler is a skill in itself. Therefore, for projects that will have a clear coat or a stain finish, the pin nailer’s near-invisibility is a massive advantage, whereas for painted trim and projects, the brad nailer’s slightly more visible hole is perfectly acceptable and much easier to fill.

Navigating Material Splitting and Delicate Work

This is a area where the pin nailer’s delicacy becomes a major asset. The extremely fine 23-gauge pin exerts so little pressure on the wood fibers that the risk of splitting is virtually eliminated. This makes it the only safe choice for nailing into the very end of a piece of wood, into exquisitely delicate moldings, or into brittle exotic hardwoods. It allows you to fasten pieces that would be impossible to secure with any other pneumatic tool without causing damage.

The brad nailer, with its thicker 18-gauge nail, carries a higher, though still relatively low, risk of splitting. This risk increases when nailing close to the end of a board, into very dry or brittle wood, or when using nails that are too long for the material thickness. While it is generally very safe, it requires a bit more forethought and caution than the pin nailer. For the vast majority of standard trim work with pine or MDF, splitting is not a common issue with a brad nailer, but it’s a crucial factor to consider when your materials are exceptionally fragile or expensive.

Making the Right Choice for Your Project

Armed with a deep understanding of each tool’s personality, the question shifts from “What’s the difference?” to “Which one is right for my project?” This is the most practical part of the journey, where we translate theory into action. The correct choice will save you time, frustration, and materials, while the wrong choice can lead to failed projects and a lot of head-scratching. Often, the answer isn’t a matter of one being universally better, but of one being specifically better for the task you have in front of you right now.

A great way to think about it is to consider the primary source of strength in your assembly. If the joint is designed to be held together by the fastener itself—like a piece of trim attached to a wall—then the brad nailer is your tool. It provides the necessary holding power. However, if the joint’s strength is coming from wood glue—like in a mitered corner of a picture frame or a cabinet door assembly—then the pin nailer is the superior choice. Its job is simply to act as a set of extra hands, holding everything perfectly in place while the glue, which forms a bond stronger than the wood itself, cures completely.

When to Confidently Reach for Your Brad Nailer

You should grab your brad nailer for any project where discreet fastening is needed, but where the nail will be the primary method of holding the materials together. Its ideal domain is general trim and molding installation. Baseboards, crown molding, chair rails, and window casings are all classic brad nailer territory. The holding power is sufficient to keep the trim securely in place on potentially uneven walls, and the holes are easy to fill before painting. It’s the perfect balance for this very common task.

You should also confidently choose the brad nailer for any light-duty assembly where you might forgo glue or where the holding power of the nail is a key component. This includes building simple crates, attaching backing to bookshelves, assembling face frames for cabinets, and constructing small furniture items like stools or side tables (where joints are also reinforced). If you are working on a project that will be painted, the brad nailer is almost always the right call, as the filled holes will be completely hidden under a coat of paint, and you gain the benefit of its stronger grip.

Situations That Demand a Pin Nailer

The pin nailer is a non-negotiable necessity when you are working on projects where any visible fastener hole would ruin the aesthetic. This is most critical in fine woodworking projects that will receive a clear coat of varnish, oil, or lacquer. Examples include building a fine jewelry box from walnut or cherry, attaching delicate inlay strips, or securing the thin dividers in a glass-front cabinet. In these cases, the nearly invisible pin hole preserves the natural beauty of the wood without distracting blemishes.

You must also use a pin nailer when the material you are fastening is so delicate that a thicker nail would split it. This includes securing fragile ornamental carvings, thin veneers, and very small pieces of trim. If you’ve ever tried to nail a tiny piece of quarter-round and watched it split in half, a pin nailer would have been your savior. It is also the best tool for complex glue-ups, as it allows you to tack parts in place without worrying about a constellation of filler spots marring your finished piece. For temporary tacking of jigs or fixtures in the workshop where you don’t want to leave a mark, the pin nailer is also incredibly useful.

The Power of Owning Both and Using Them in Tandem

For the serious DIYer or the professional woodworker, the most powerful strategy is not to choose one over the other, but to own both and use them as a team. Having both a pin nailer and a brad nailer in your arsenal gives you an incredible level of control and flexibility. You can tackle a much wider range of projects and handle complex assemblies with a level of finesse that is otherwise impossible. Many seasoned craftspeople use them in concert on the same project to leverage the unique advantages of each.

A classic example of this tandem approach is building a cabinet door. You might use the brad nailer to assemble the main stiles and rails of the door frame, where the extra holding power is beneficial for the structural joint. Then, when it comes to attaching a very delicate, thin molding to the face of that door, you would switch to the pin nailer to avoid any risk of splitting the fragile accent piece. Another example is installing a complex piece of crown molding. You could use the brad nailer at the top and bottom where more strength is needed to pull it tight to the wall and ceiling, and use the pin nailer for the delicate coped joint in the corner to prevent blow-out. This synergistic use is the mark of a true craftsperson.

Beyond the Basics: Power Sources and Pro Tips

While the core debate of pin nailer vs brad nailer revolves around their application, it’s also worth touching on the platform itself. Both tools are available in three main types: pneumatic, cordless, and battery-powered. Pneumatic models are the traditional choice, powered by an air compressor. They are lightweight, incredibly reliable, and have a great power-to-weight ratio. The downside is you are tethered to a compressor and air hose, which can limit mobility and add noise to your workspace.

Cordless nailers have surged in popularity in recent years. These are powered by a rechargeable battery platform, just like a modern drill or saw. The major advantage is complete portability and freedom from hoses. You can work anywhere without the constant hum of a compressor. The trade-offs have historically been increased weight, higher initial cost, and the potential for the tool to have slightly less consistent power as the battery drains. However, the technology has improved dramatically, and for most users, the performance of a modern cordless brad or pin nailer is more than adequate. Your choice here will depend on your workspace, your budget, and how much you value untethered freedom.

Essential Tips for Flawless Operation

No matter which tool you choose, using it correctly is key to a professional outcome. First and foremost, always use the correct length of fastener. A good rule of thumb is that the nail should be long enough to penetrate into the underlying material by at least three times the thickness of the piece you are nailing. For baseboard, this usually means a 2-inch nail into the wall studs. For attaching a 1/4-inch thick plywood back, a 3/4-inch or 1-inch nail is perfect. Using nails that are too long can cause blow-out on the other side or damage hidden wiring/pipes.

Secondly, always wear safety glasses. This is non-negotiable. Nailers can cause fasteners to ricochet or fragments of material to fly back towards you. Hearing protection is also a good idea, especially with pneumatic tools. Finally, practice on scrap pieces of the same material before starting your actual project. This allows you to adjust the air pressure on a pneumatic tool (or the power setting on a cordless one) to set the nail at the perfect depth—just below the surface without crushing it. A little practice ensures that your first nail on the real project is driven perfectly.

Maintaining Your Tools for Longevity

Like any precision tool, your nailers deserve a little care to keep them running smoothly for years. For pneumatic tools, this means adding a few drops of special air tool oil into the air inlet every day you use it. This oils the internal O-rings and keeps the mechanism working smoothly. It’s also crucial to use an in-line moisture filter on your air compressor to prevent water from entering the tool and causing rust. For cordless models, keep the batteries charged according to the manufacturer’s instructions and store them in a cool, dry place.

Periodically, you should give the tool a thorough cleaning. Wipe down the exterior to remove dust and grime, and use a small brush or compressed air to clean out the nose piece where the nails exit, as sawdust can accumulate here and cause jams. If a jam does occur, always disconnect the air hose or remove the battery before attempting to clear it. Following the manufacturer’s specific instructions for clearing jams will prevent damage to the tool and keep you safe. A well-maintained nailer is a reliable partner in your workshop.

Conclusion

The journey through the world of pin nailers and brad nailers reveals that the choice between them is not about finding a single “best” tool, but about matching the right tool to the specific demands of your project. The brad nailer stands as the versatile champion, an indispensable tool for the workshop that provides an excellent blend of holding power and discretion. It is the go-to for trim work, light assembly, and any situation where the fastener itself bears the load. For the DIYer looking to buy their first finish nailer, the 18-gauge brad nailer is almost always the most logical and useful starting point.

The pin nailer, on the other hand, is the specialist you call upon when the situation demands absolute stealth and delicacy. It is the secret weapon for fine woodworking, the savior of fragile moldings, and the ultimate glue-up assistant. Its near-invisible fastening capability is unrivaled, making it essential for projects finished with clear coats or made from expensive, brittle materials. While it may not be the first nailer you buy, it is a tool that will elevate the quality and finesse of your work once your skills and project complexity grow. Ultimately, understanding the fundamental difference between a pin nailer vs brad nailer empowers you to work smarter, not harder, and achieve clean, professional, and lasting results on every single project.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main physical difference between a pin nail and a brad nail?

The most obvious physical difference is the head. A brad nail has a very small, T-shaped head that provides a small amount of clamping force and helps with holding power. A pin nail is completely headless; it is just a straight, slender pin of metal. This is why a pin nailer leaves an almost invisible hole but offers very little independent gripping strength.

Can I use a brad nailer for all the same things as a pin nailer?

While you can sometimes substitute a brad nailer in a pinch, it is not recommended for the delicate tasks a pin nailer excels at. The thicker 18-gauge brad nail has a much higher risk of splitting very thin or brittle materials. Furthermore, the hole it leaves is significantly more visible, which can ruin the finish on a clear-coated project. The pin nailer vs brad nailer debate really hinges on this trade-off between strength and stealth.

Is the holding power of a pin nailer really that bad?

Yes, when considered on its own, the holding power of a pin nail is minimal. It provides almost no resistance to being pulled straight out. However, this misses the point of the tool. A pin nailer is designed to be used in conjunction with wood glue. The glue provides 100% of the long-term strength; the pin’s only job is to hold the pieces perfectly in place while the glue cures. Used correctly in this way, the joint is incredibly strong.

I’m just starting out. Which one should I buy first?

For the vast majority of beginners, a brad nailer is the more practical and versatile first purchase. An 18-gauge brad nailer can handle about 80% of the common tasks a DIYer will encounter, such as installing trim, building small projects, and assembling furniture. It provides enough holding power to be useful on its own and is forgiving enough for general use. You can always add a pin nailer later as you take on more delicate, fine woodworking projects.

Are there any projects where I should avoid both of these tools?

Absolutely. Neither a pin nailer nor a brad nailer should be used for structural framing, building decks, installing hardwood flooring, or any application where building codes or structural integrity are a concern. For these tasks, you need framing nailers, finish nailers (15 or 16-gauge), or specialized flooring nailers. The pin nailer vs brad nailer discussion is strictly for fine, non-structural finish work and light assembly.

Comparison Table: Pin Nailer vs Brad Nailer

| Feature | Brad Nailer | Pin Nailer |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Versatile fastening for trim & assembly | Invisible fastening for delicate work & glue-ups |

| Nail Gauge | 18-Gauge (thicker) | 23-Gauge (thinner) |

| Nail Head | Small T-shaped head | Headless |

| Holding Power | Good; can be used alone for light duty | Minimal; must be used with glue |

| Hole Visibility | Small, requires wood filler | Very small, often self-healing or needs only light sanding |

| Risk of Splitting | Low, but possible on delicate materials | Very low, ideal for brittle woods |

| Common Nail Lengths | 5/8″ to 2″ | 1/2″ to 1 3/8″ (up to 2″ in some models) |

| Best For | Baseboards, crown molding, picture frames, face frames | Delicate trim, veneers, intricate moldings, complex glue-ups |

Quotes

“A brad nailer is for when you need it to stay put; a pin nailer is for when you need it to look like it was never nailed at all.”

— A Veteran Cabinetmaker

“The choice between a pin nailer and a brad nailer is the craftsman’s most common crossroads between brute strength and elegant subtlety.”

— A Furniture Restoration Specialist