Welcome to the wonderful, and sometimes confusing, world of Japanese pantry essentials. If you’ve ever stood in the Asian foods aisle, staring at two similar-looking bottles labeled “mirin” and “rice vinegar,” and felt a wave of uncertainty, you are not alone. These two staples are fundamental to the complex, umami-rich flavors we associate with Japanese cooking, but they are far from interchangeable. Using one in place of the other can be the difference between a dish that sings with authentic flavor and one that falls completely flat.

Understanding the distinction between mirin and rice vinegar is like learning the secret handshake to a culinary club. It empowers you to recreate your favorite restaurant dishes at home with confidence and to experiment with new flavors. This comprehensive guide is your deep dive into everything you need to know. We will explore their unique identities, from production and flavor profiles to their specific roles in the kitchen. We will debunk common myths, offer practical substitutes, and provide the knowledge you need to use each one like a pro. So, let’s demystify these two iconic ingredients and settle the mirin vs rice vinegar debate once and for all.

What is Mirin? The Sweet Soul of Japanese Glazes

Let’s start with mirin, the ingredient that often causes the most confusion. At its core, mirin is a sweet rice wine. Think of it less as a drinking wine and more as a dedicated cooking seasoning, although there are premium grades that can be sipped. Its primary role in the kitchen is to introduce a gentle, rounded sweetness, a beautiful glossy sheen, and to help balance salty and savory flavors. It is the magic behind the irresistible glaze on teriyaki chicken, the subtle sweetness in sukiyaki broth, and the key to preventing fish from falling apart when simmering.

The traditional production of mirin is a patient art. It involves steaming glutinous (mochi) rice, combining it with koji (a mold culture, Aspergillus oryzae, which is also used to make sake and soy sauce), and then mixing it with shochu, a distilled spirit. This mixture is then left to ferment and mature for anywhere from two months to two years. The koji enzymes break down the rice starches into sugars, resulting in a sweet, aromatic, and slightly alcoholic liquid. The alcohol content, typically around 14%, is not just a byproduct; it plays a crucial role in extracting flavors from other ingredients and mitigating strong fishy or gamey odors.

The Different Types of Mirin You’ll Encounter

When you go shopping, you’ll find that not all bottles labeled “mirin” are created equal. The landscape has changed to include cheaper, mass-produced alternatives that bypass the traditional fermentation process. Knowing the differences is key to selecting the right product for your cooking. First, there is Hon Mirin, which translates to “true mirin.” This is the real deal, made through the traditional fermentation process described above. It contains alcohol, has a complex, nuanced sweetness, and is the highest quality option, though it’s also the most expensive. You’ll often find it in well-stocked Japanese grocery stores or online.

Next, we have Mirin-fu Chomiryo, or “mirin-like seasoning.” This is the most common type found in general supermarkets. To avoid alcohol taxes, manufacturers produce this version with less than 1% alcohol. It’s made by combining glucose, corn syrup, water, rice vinegar, and flavorings to mimic the taste of real mirin. While it will provide sweetness, it lacks the depth and complexity of hon mirin. Finally, there’s Shio Mirin, which is “salted mirin.” A small amount of salt is added to, again, classify it as a seasoning rather than an alcoholic beverage for tax purposes. The salt content is minimal and generally won’t affect the taste of your dish, but it’s something to be aware of if you’re watching your sodium intake.

What is Rice Vinegar? The Tangy Workhorse

Now, let’s turn to rice vinegar. If mirin is the sweet soul, rice vinegar is the tangy, acidic workhorse of the Japanese pantry. As the name clearly states, it is a vinegar. It is produced by fermenting the sugars in rice first into alcohol (like sake) and then, through a second fermentation process, into acetic acid. This is the same fundamental process used to make any vinegar, like apple cider or white wine vinegar. The result is a pale yellow liquid with a clean, mild, and delicately sharp acidity that is less harsh and more nuanced than most Western vinegars.

Rice vinegar’s primary function is to add a bright, acidic punch. It cuts through richness, tenderizes proteins, and acts as a key component in pickling, where its acidity preserves vegetables and creates that classic tangy flavor. You will find it in everything from the dressing for a crisp cucumber sunomono salad to the sushi rice that forms the base of your favorite rolls. Its acidity is essential for balancing the sweetness of the sugar and the saltiness of the soy sauce in many classic Japanese preparations, creating a harmonious flavor profile that is never one-dimensional.

The Varieties of Rice Vinegar

While the basic concept is the same, there are a few common types of rice vinegar to know. The most versatile and widely used is Seasoned Rice Vinegar or Sushi Vinegar. This is a huge time-saver. Manufacturers add sugar, salt, and sometimes MSG or kombu (kelp) extract to plain rice vinegar, creating a pre-mixed solution specifically for seasoning sushi rice. If a recipe calls for seasoning sushi rice with separate ingredients and you use this, you’ll end up with an overly salty and sweet result, so always check your labels carefully.

Then we have Plain Rice Vinegar or Unseasoned Rice Vinegar. This is the pure, unadulterated product—just rice vinegar. This is what you should use for making pickles, crafting your own dressings, and adding a splash of acidity to sauces and marinades. It gives you complete control over the balance of sweet, salty, and sour in your dish. Beyond these, you might encounter Black Rice Vinegar (a darker, stronger Chinese variety) and Red Rice Vinegar (another Chinese variant), but for classic Japanese cooking, plain and seasoned are your go-to choices.

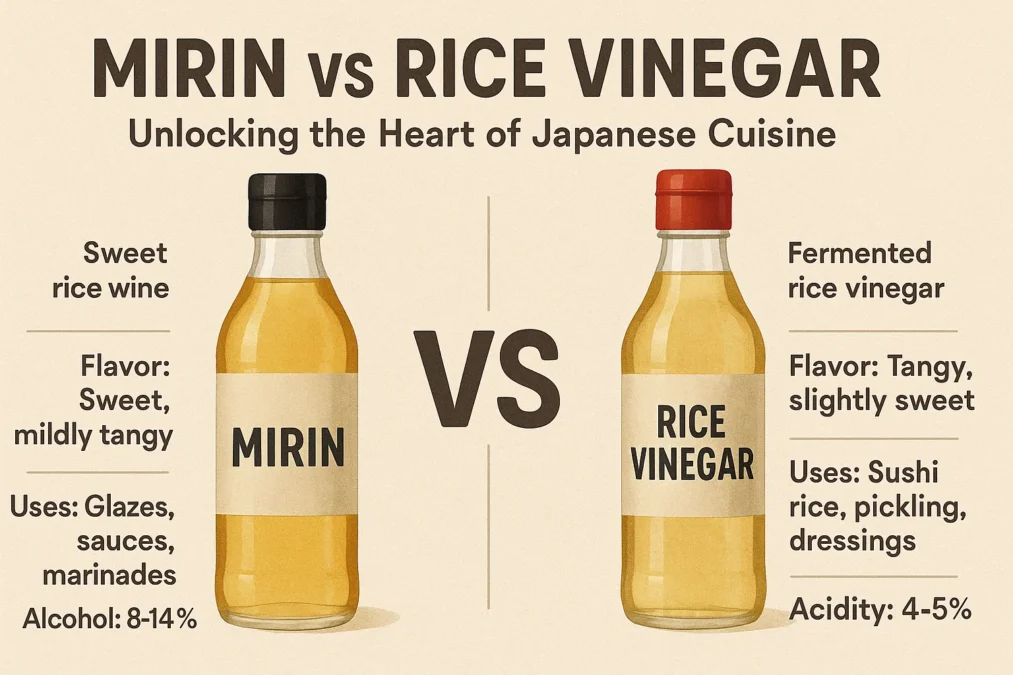

The Fundamental Differences: A Head-to-Head Look

Now that we have a solid understanding of each ingredient individually, let’s put them side-by-side. The core of the mirin vs rice vinegar confusion lies in their base nature. Mirin is a sweet wine, while rice vinegar is a sour acid. This fundamental difference dictates every aspect of how they are used. Imagine comparing a bottle of maple syrup to a bottle of lemon juice; they might look vaguely similar in the bottle, but their impact on a dish could not be more different. This is the level of distinction we’re talking about here.

Their production processes, while both involving fermented rice, diverge significantly. Mirin is a single fermentation process where starches are converted to sugars, resulting in a sweet, alcoholic product. Rice vinegar is a double fermentation process (sugar to alcohol, alcohol to acid), resulting in a sour, non-alcoholic (or very low alcohol) product. This difference is the very reason why a sip of mirin would taste sweet and syrupy, while a sip of rice vinegar would make you pucker up.

A Detailed Comparison Table

To make the distinctions crystal clear, here is a table breaking down the key characteristics in the mirin vs rice vinegar debate.

| Feature | Mirin | Rice Vinegar |

|---|---|---|

| Core Identity | Sweet Rice Wine | Fermented Acidic Condiment |

| Primary Flavor | Sweet, mild, complex, slightly alcoholic | Tangy, sharp, clean, acidic |

| Primary Function | Adds sweetness, glaze, and depth; balances saltiness | Adds acidity and brightness; used in pickling and dressings |

| Alcohol Content | ~14% (Hon Mirin); <1% (Mirin-fu) | Typically 0% (trace amounts possible) |

| Acidity Level | Very Low | High (typically 4-5% acidity) |

| Key Uses | Teriyaki, glazes, simmered dishes (nimono), sauces | Sushi rice, sunomono, pickles, marinades, dipping sauces |

| Sugar Content | High (from natural fermentation or added syrup) | Low (unless pre-seasoned) |

| Substitute | Sweet sherry, sweet sake with a bit of sugar | Apple cider vinegar, white wine vinegar (with slight sugar) |

Mastering the Uses: When to Reach for Which Bottle

Understanding the theory is one thing; knowing which bottle to grab in the heat of cooking is another. Let’s translate our knowledge into practical kitchen action. Your choice fundamentally depends on the flavor profile you are trying to achieve. Are you looking for a deep, caramelized sweetness and a glossy finish? Your answer is mirin. Are you aiming for a bright, tangy pop to cut through fat or to preserve and pickle? Your hand should reach for the rice vinegar.

Mirin is your best friend for all things rich and glossy. It is the undisputed champion of the mirin vs rice vinegar battle when it comes to glazes. When you’re making teriyaki sauce, the mirin doesn’t just add sweetness; its sugars caramelize under heat, creating that beautiful, sticky, lacquered coating on the chicken or fish. In simmered dishes like nikujaga (a meat and potato stew) or oden, mirin works alongside soy sauce and dashi to create a deeply savory, slightly sweet broth that penetrates the ingredients. It also works wonders in marinades, where its mild acidity and alcohol help tenderize meat while its sweetness ensures a beautifully browned surface.

The Irreplaceable Role of Rice Vinegar

Rice vinegar, on the other hand, is the guardian of freshness and brightness. Its most famous role is in seasoning sushi rice. The slight acidity of the rice vinegar mixture not only adds a delightful tang that complements the fish but also acts as a preservative and lowers the pH of the rice, making it safer to consume. In salads like sunomono, a splash of rice vinegar mixed with a touch of soy sauce and mirin creates a light, refreshing dressing that awakens the palate. It is also the essential component for making tsukemono (Japanese pickles), from the quick, crunchy cucumber pickles to the longer-fermented takuan (pickled daikon).

Perhaps one of the most important, yet subtle, uses for rice vinegar is as a flavor balancer. In many Japanese sauces and dips, you will find a small amount of rice vinegar. Why? Because it provides the necessary acidic counterpoint to the salty umami of soy sauce and the rounded sweetness of mirin. This trio—soy sauce, mirin, and rice vinegar—often works in harmony to create a perfectly balanced flavor profile that is greater than the sum of its parts. Without the vinegar, the sauce could taste cloying or one-dimensionally salty.

Bleached vs Unbleached Flour: The Ultimate Guide to Choosing the Right Flour for Your Kitchen

The Substitution Conundrum: What to Do in a Pinch

We’ve established that mirin and rice vinegar are not direct substitutes. However, we all find ourselves in a situation where we’re halfway through a recipe and realize we’re out of a key ingredient. So, what can you do? The goal when substituting is to mimic the function of the missing ingredient, not necessarily its exact flavor. For mirin, you need to replicate sweetness and a touch of complexity. For rice vinegar, you need to provide a clean, mild acidity.

If you need a mirin substitute, you have a few options. A good dry sherry or sweet Marsala wine mixed with a small pinch of sugar can work well, as they provide both the alcoholic element and the sweetness. If you don’t cook with alcohol, a mixture of white grape juice or apple juice with a tiny bit of lemon juice and a pinch of sugar can mimic the effect, though it will be fruitier. Some people suggest using sugar or maple syrup alone, but this only addresses the sweetness and misses the complexity and the functional properties of the alcohol, so use this as a last resort.

Finding a Stand-in for Rice Vinegar

Substituting for rice vinegar is generally a bit easier because its profile is more straightforward. The best substitute is another mild vinegar. Apple cider vinegar is an excellent choice; its fruity notes are a good match for the mildness of rice vinegar. Use it in a 1:1 ratio. White wine vinegar is another solid option, though it can be slightly more sharp, so you might want to add a tiny pinch of sugar to round it out. In an absolute emergency, you could use lemon or lime juice, which will provide the acidity but will also impart a distinct citrus flavor that may not be desired in all dishes.

A crucial word of warning: never, ever substitute one for the other directly. Using rice vinegar when a recipe calls for mirin will make your dish unpleasantly sour and acidic, completely overpowering any other flavors. Conversely, using mirin in place of rice vinegar will make your dish cloyingly sweet and unbalanced. It will lack the necessary acidic “punch” to brighten up a salad dressing or properly season sushi rice. In the great mirin vs rice vinegar dilemma, a direct swap is the quickest way to culinary disappointment.

Flavor Profiles and Synergy: How They Work Together

To truly master Japanese cooking, you need to stop thinking of mirin and rice vinegar as rivals and start seeing them as the best of friends—a dynamic duo that, when used in concert, creates culinary magic. They are the yin and yang of the flavor world. Mirin brings the sweet, mellow, rounded depth, while rice vinegar brings the sharp, bright, clarifying tang. Alone, they are potent specialists; together, they create a balanced and complex foundation for countless dishes.

Consider a classic dipping sauce for gyoza or tempura. It’s typically a blend of soy sauce (salty/umami), rice vinegar (acidic), and a touch of mirin (sweet). Each component plays its role. The soy sauce provides the savory base, the mirin rounds out the saltiness and adds body, and the rice vinegar cuts through the oiliness of the fried food, cleansing the palate with every bite. Remove the vinegar, and the sauce feels heavy and flat. Remove the mirin, and it becomes harshly salty and sharp. It is this synergy that defines the balanced nature of washoku (Japanese cuisine).

Building a Balanced Pantry

For anyone serious about exploring Japanese flavors, having both a good bottle of hon mirin (or a quality mirin-fu seasoning) and a bottle of unseasoned rice vinegar is non-negotiable. They are two of the “Sa-Shi-Su-Se-So” of Japanese cooking, a classic pentad of core seasonings: Sato (Sugar), Shio (Salt), Su (Vinegar), Seuyu (Soy Sauce), and Miso. Here, “Su” refers to rice vinegar. While mirin isn’t explicitly in this classic list, it is an indispensable part of the modern kitchen, often working alongside soy sauce and dashi as a foundational flavor builder.

Having both ingredients on hand gives you the freedom and flexibility to create authentic tastes. You can whip up a tangy salad dressing by combining rice vinegar, soy sauce, a dash of mirin, and sesame oil. You can create a rich teriyaki glaze by simmering soy sauce, mirin, and sake, knowing that the mirin is doing its job of providing sweetness and sheen. You can make a batch of perfect sushi rice by carefully seasoning with a mixture of rice vinegar, sugar, and salt. Trying to navigate Japanese recipes with only one of these ingredients is like trying to paint a full-color picture with only half the palette.

Common Myths and Mistakes to Avoid

Even with a better understanding, a few persistent myths surround the mirin vs rice vinegar topic. Let’s clear those up right now. One of the biggest misconceptions is that they are similar enough to be used interchangeably. We’ve hopefully laid that myth to rest, but it’s worth repeating: substituting one for the other will dramatically and often unpleasantly alter your final dish. They serve opposite purposes on the flavor spectrum.

Another common mistake is assuming that all mirin is non-alcoholic. While the most common supermarket “mirin-fu chomiryo” has very little alcohol, traditional hon mirin contains about 14% alcohol. This is important for those who avoid alcohol for dietary, religious, or health reasons. Always check the label carefully. Conversely, some people believe rice vinegar is alcoholic, which it is not. The fermentation process converts the alcohol into acid, leaving a negligible amount, if any, in the final product.

The “Just Use Sugar” Trap

A frequent piece of bad advice is to substitute mirin with plain sugar or honey. While this will add sweetness, it misses all the other qualities mirin brings. Sugar only sweetens; it doesn’t contribute the complex fermented flavor, the beautiful glaze-enhancing properties, or the ability to tenderize and reduce unwanted odors. As one renowned Japanese chef puts it,

“Mirin is not merely a sweetener; it is a flavor architect. It builds depth and rounds out harsh edges in a way that simple sugar never could.”

Similarly, using a harsh vinegar like distilled white vinegar in place of mild rice vinegar can be a disaster. Its aggressive acidity will overpower delicate flavors and leave an unpleasant, sharp aftertaste. When a recipe calls for rice vinegar, it’s for its specific mild and clean acidity. If you must substitute, always opt for the mildest vinegar you have, like apple cider or white wine vinegar.

Selecting and Storing Your Ingredients

To get the most out of your mirin and rice vinegar, selecting quality products and storing them correctly is key. When buying mirin, your first priority should be to read the ingredient list. Look for “hon mirin” if you can find it. The ingredients should be simple: rice, koji, and shochu (or alcohol). Avoid products that list corn syrup, glucose syrup, or high fructose corn syrup as the first ingredient, as these are lower-quality mirin-like seasonings. They will work in a pinch but won’t deliver the same depth of flavor.

For rice vinegar, the choice is simpler. For maximum versatility, buy a bottle of unseasoned or plain rice vinegar. This allows you to control the salt and sugar levels in all your dishes. If you make sushi very frequently, you might also keep a bottle of seasoned rice vinegar on hand for convenience, but know that it limits your use for other applications. Look for a brand that uses natural brewing processes for the best flavor.

Keeping Your Pantry Staples Fresh

Both mirin and rice vinegar have impressively long shelf lives, but they are not immortal. Thanks to its high sugar and alcohol content, hon mirin is very stable. Once opened, it’s best to store it in a cool, dark place, like a pantry. It does not need to be refrigerated, though doing so can help preserve its flavor for even longer, especially if you don’t use it frequently. Mirin-fu seasoning, with its lower alcohol content, is more prone to degradation and is best stored in the refrigerator after opening to maintain its quality.

Rice vinegar, with its high acidity, is a natural preservative itself and is very stable. An unopened bottle can be stored in the pantry for years. Once opened, it will also keep perfectly well in the pantry for 1-2 years without any loss of quality. There is no need to refrigerate it. However, if you have the space, refrigerating it can help retain its peak flavor profile for an extended period. Always ensure the caps are tightly sealed to prevent evaporation and contamination.

Conclusion: Embracing Two Essential Flavors

The journey through the world of mirin vs rice vinegar reveals a story not of competition, but of beautiful complement. Mirin, the sweet, glossy, depth-building wine, and rice vinegar, the sharp, bright, acidic workhorse, are two pillars supporting the magnificent structure of Japanese cuisine. They are fundamentally different in nature, production, and purpose, and understanding this distinction is a transformative step in your culinary education.

Embrace them both. Let mirin be your go-to for creating irresistible glazes, rich simmered dishes, and well-balanced marinades. Let rice vinegar be your secret weapon for crafting perfect sushi rice, brightening salads, making quick pickles, and adding a final acidic lift to sauces and dips. Stock your pantry with a good bottle of each, and you will unlock the ability to recreate authentic Japanese flavors in your own kitchen. So, the next time you face that aisle, you can confidently reach for both, knowing that you hold the keys to sweet and sour harmony.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use mirin instead of rice vinegar in sushi rice?

Absolutely not. This is one of the most critical distinctions in the mirin vs rice vinegar discussion. Using mirin in sushi rice would make it unacceptably sweet and cloying, completely overpowering the delicate flavor of the fish. The primary role of rice vinegar in sushi rice is to provide a sharp, acidic tang that both seasons the rice and acts as a mild preservative. Substituting mirin would ruin the entire dish.

What is a good non-alcoholic substitute for mirin?

If you are avoiding alcohol, your best bet is to look for a specifically labeled “alcohol-free mirin” or “mirin-fu chomiryo,” which contains less than 1% alcohol. If you can’t find that, you can create a simple substitute by combining 1 tablespoon of apple juice or white grape juice with a teaspoon of sugar and a tiny pinch of lemon juice to mimic the complexity. This won’t be perfect, but it will provide the needed sweetness.

Does rice vinegar taste the same as white vinegar?

No, they are quite different. White vinegar is typically made from grain alcohol and has a very sharp, harsh, and straightforward acidic punch. Rice vinegar, made from fermented rice, is significantly milder, less acidic, and has a subtle, slightly sweet, and complex flavor profile. In recipes calling for rice vinegar, substituting white vinegar can easily overpower the other ingredients.

Why do so many recipes use both mirin and rice vinegar?

Recipes use both because they perform opposite but complementary functions, creating a balanced flavor profile. Think of them as the sweet and sour in sweet and sour sauce. The mirin provides a rounded, caramel-like sweetness and body, while the rice vinegar provides a bright, clean acidity to cut through the sweetness and richness. Together with salty elements like soy sauce, they create the complex, umami-rich taste that is the hallmark of Japanese cooking.

How can I tell if my mirin has gone bad?

Mirin is very stable due to its sugar and alcohol content, but it can eventually degrade. Signs that your mirin has gone bad include a noticeably sour or vinegary smell (indicating it has started to acetify into vinegar), a change in color to a much darker shade, or the presence of mold or off odors. If it smells or tastes unpleasant, it’s best to discard it. Proper storage in a cool, dark place will maximize its shelf life.