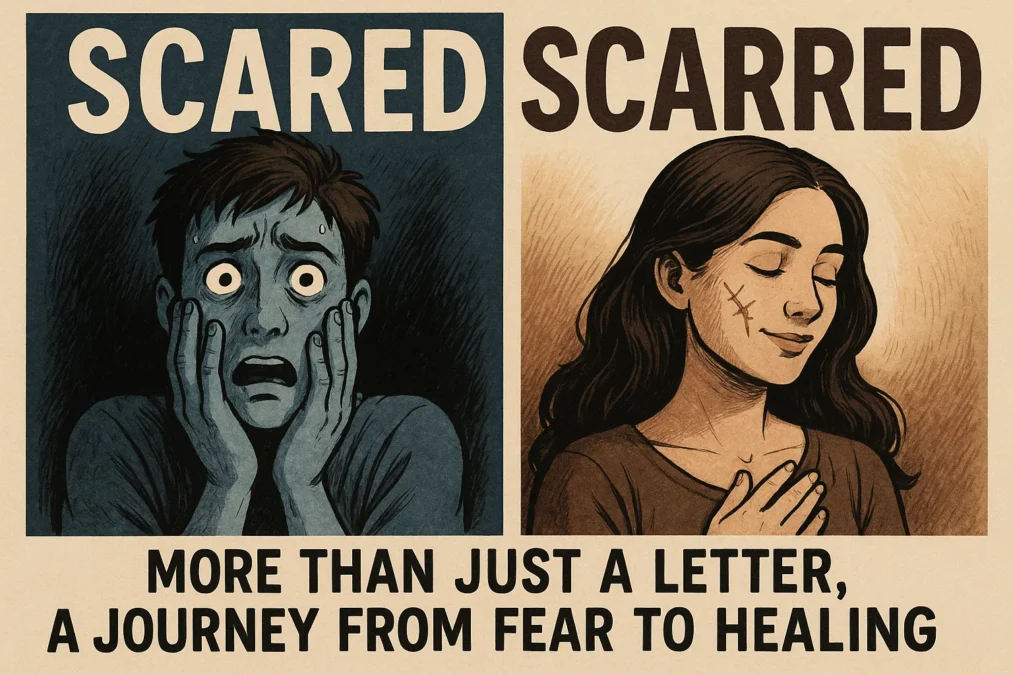

Scared vs Scarred: It’s a single letter, a tiny shift in spelling, yet it represents a chasm of meaning in the human experience. We’ve all been there—typing a quick message, writing an important email, or crafting a social media post, when suddenly we pause. Is it “scared” or “scarred”? The words sound identical when spoken, but they live in entirely different neighborhoods of our emotional and physical lives. One is a temporary state, a fleeting rush of adrenaline. The other is a lasting mark, a story etched onto the canvas of our being. Understanding the difference between being scared and being scarred is more than a grammar lesson; it’s a profound exploration of how we process fear, trauma, and the events that shape us.

This confusion is a classic example of a homophone mix-up, but it’s one packed with significance. Getting it right matters not just for clear communication, but for acknowledging the real and lasting impact of life’s difficult moments. When we say we are “scarred for life,” it carries a weight that “scared for life” simply does not. This article will do more than just define these two words. We will delve deep into their origins, their psychological implications, and the crucial journey from one to the other. We will explore how a moment of being profoundly scared can, under certain conditions, leave us permanently scarred, and more importantly, how we can learn to heal and integrate those scars into our personal story. Let’s begin by breaking down the immediate, heart-pounding state of being scared.

Understanding the Word “Scared”

When we say we are scared, we are describing a fundamental, immediate human emotion: fear. This feeling is an integral part of our biological wiring, a primal alarm system designed to keep us alive. Think of the sudden jolt you feel when a car honks loudly as you step off a curb, or the heart-pounding suspense you experience while watching a horror movie, even though you know you’re safe on your couch. That is the essence of being scared. It’s a transient emotional and physiological response to a perceived threat. Your body kicks into high gear, releasing a cocktail of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. Your heart rate accelerates, your muscles tense, your senses become hyper-aware—all preparing you for the “fight, flight, or freeze” response. This state is intense but, crucially, it is temporary.

The word “scared” itself comes from the Old Norse word “skirra,” meaning “to frighten.” It functions primarily as an adjective, describing the state of the person experiencing the fear. You are scared. You feel scared. It’s a condition of the self in a specific moment. This temporariness is its key characteristic. Once the threat passes—the near-miss accident is avoided, the jump-scare in the film ends, the loud noise is identified—the fear subsides. Your heart rate returns to normal, the tension drains from your shoulders, and the feeling fades. Being scared is like a sudden, violent storm; it can be terrifying while it lasts, but the skies eventually clear. It doesn’t inherently change who you are; it’s a reaction you have. This makes it distinctly different from its homophone, which describes not a passing storm, but a permanent change in the landscape.

Understanding the Word “Scarred”

If “scared” is the storm, then “scarred” is the erosion it leaves behind. The word “scarred” is all about permanence and lasting impact. It originates from the Greek word “eskhara,” meaning “scab” or “hearth,” and it refers to a mark left on the skin or any tissue after a wound has healed. When we talk about being scarred, we are speaking of a physical or psychological mark that remains long after the injurious event is over. A physical scar tells a story of a past injury—a surgery, a deep cut, a burn. It is a visible testament to the body’s incredible, albeit imperfect, healing process. The wound has closed, but the evidence remains, a permanent fixture on your skin.

However, the concept of being scarred extends far beyond the physical. Emotional and psychological scarring is just as real, and often more profound. This occurs when a deeply distressing or disturbing experience—a trauma—wounds the psyche. Unlike the temporary fear of being scared, an emotional scar signifies a fundamental change in how a person sees themselves, others, or the world. It can manifest as lasting anxiety, trust issues, phobias, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The event is over, but the individual is left with a residual emotional structure that influences their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors for years, sometimes a lifetime. The word “scarred” is the past participle of the verb “to scar,” and this grammatical structure emphasizes the completed action and its enduring result. You have been scarred. The event has left its mark on you, transforming you in some way. It’s not a state you are in, but a quality you now carry.

The Key Differences Between Scared and Scarred

The core distinction between these two words can be summarized as temporary emotion versus permanent mark. This is the foundational concept that separates a passing feeling from a lasting change. Being scared is an emotional and physiological response that exists in the present moment. It is the body’s alarm system. When the threat is gone, the alarm silences, and the body returns to its baseline state. There is no inherent lasting change. You can be scared of a spider one moment and completely fine the next once it’s been removed from the room. The experience, while potent, is contained.

Being scarred, on the other hand, is fundamentally about alteration. It is the evidence of a wound that has healed but has left a permanent record. This record can be physical, like a scar from a childhood fall, or psychological, like the deep-seated fear of abandonment after a painful breakup. The key is that the person is different after the event. The scar becomes a part of their history and their identity. A soldier might have been scared during a battle—a temporary, intense fear—but may come home scarred by the trauma, experiencing flashbacks and anxiety for decades. The fear was the experience; the scar is the legacy.

Another crucial difference lies in their grammatical roles and usage. “Scared” is primarily used as an adjective (I am scared) or the past tense of the verb “to scare” (The movie scared me). It describes a state or an action. “Scarred,” however, is primarily used as an adjective derived from the past participle of the verb “to scar” (I am scarred; The accident scarred him for life). This usage underscores that the action of scarring has been done to the subject, and the effect is ongoing. You wouldn’t say, “I am scaring easily” to mean you have many scars; you would say, “I scar easily.” This grammatical distinction mirrors the real-world difference: one is a current feeling, the other is a lasting condition resulting from a past action.

The Psychological Journey: From Scared to Scarred

How does a temporary feeling of being scared solidify into a permanent state of being scarred? This journey is at the heart of understanding trauma and resilience. Not every frightening event leads to lasting scars. The transformation hinges on several factors, including the intensity of the event, its duration, the individual’s personal resilience, and the support systems available to them in the aftermath. A single, startling noise might make you jump (scared), but it’s unlikely to leave a psychological scar. However, a prolonged period of intense fear, a single event of extreme terror, or a perceived inescapable threat can cross a threshold.

When the fear is so overwhelming that it shatters an individual’s sense of safety and security, the brain’s normal processing mechanisms can fail. The memory of the event, along with the intense fear, may not be properly integrated into the narrative of the person’s life. Instead, it gets “stuck” in the amygdala, the brain’s fear center, leading to a lasting scar. This is the foundation of post-traumatic stress. The individual is no longer just remembering a scary event; they are reliving it through flashbacks, nightmares, and hypervigilance. The temporary state of fear has become a permanent lens through which they view the world. They are now scarred.

This journey isn’t just about the event itself, but about what happens next. The presence of a strong support network, the ability to talk about the experience, and access to therapeutic resources can be the difference between a wound that scars and one that heals more fully. Without processing and integration, the intense fear etches itself deeper, creating the scar. This is why two people can experience the same frightening event—one may recover and simply remember being scared, while the other may be profoundly scarred, their life trajectory altered by the trauma. The event was the same, but the internal and external resources for healing were not.

Common Phrases and Idioms Using Scared and Scarred

Both words are embedded in our common language through idioms and phrases, and using the correct term is vital for the meaning to land correctly. Misusing them can lead to confusion or, in some cases, a complete misunderstanding of the intended message. Let’s explore some of the most common expressions.

For “scared,” we have phrases that emphasize the temporary, often intense, nature of fear. “Scared to death” is a hyperbolic way of saying you were extremely frightened. “Scared stiff” or “scared out of my wits” vividly describe the paralyzing effect of sudden fear. “Scaredy-cat” is a playful, childish taunt for someone who is easily frightened. These phrases all point to a reaction, a moment in time where fear takes over. They do not imply any lasting damage.

The phrases for “scarred,” however, are almost universally heavy with implication. “Scarred for life” is the most direct, stating unequivocally that an experience has caused a permanent change. “Emotionally scarred” specifies that the damage is psychological rather than physical. “Battle-scarred” can refer literally to a soldier’s physical wounds or metaphorically to anyone who has endured a long and difficult struggle, emerging with the marks to prove it. Using “scared” in these contexts would completely undermine their meaning. Saying you were “scared for life” would technically mean you experienced a single, continuous moment of fear for your entire life, which is not the same as carrying the lasting impact of a past event. The idioms themselves reinforce the core definitions: scared is a reaction, scarred is a record.

The Impact of Misunderstanding Scared vs Scarred

Using “scared” and “scarred” interchangeably is more than a simple grammatical error; it can lead to significant miscommunication and a failure to acknowledge the gravity of someone’s experience. In casual conversation, a friend might laugh off your mistake if you say, “That horror movie left me scarred!” when you really meant “scared.” But in more serious contexts, the wrong word can minimize a person’s suffering or create confusion about what they are actually trying to convey.

Imagine a person confiding in a friend about a past trauma. If they say, “I was really scared by that event,” it frames the experience as a past fear, something that is over and done with. However, if they intend to communicate that they are still deeply affected, the correct word is “scarred.” Saying, “I was scarred by that event,” sends a powerful message about lasting impact. It tells the listener that the event wasn’t just frightening in the moment; it changed them. In a therapeutic, medical, or legal setting, this distinction becomes critically important. A therapist needs to know if a client is describing a current phobia (making them scared of spiders) or a deep-seated trauma from a childhood incident (that left them scarred and with a lasting anxiety disorder). The treatment approaches for these two scenarios are vastly different.

Furthermore, the misuse of these words can reflect a broader cultural tendency to trivialize trauma. When people say they are “scarred” by a bad meal or a boring meeting, they are diluting the power of the word and, by extension, unintentionally minimizing the experiences of those who live with genuine psychological scars. Precision in language matters because it fosters empathy and understanding. Using the right word shows that you comprehend the difference between a passing discomfort and a life-altering wound.

To vs Too: The Ultimate Guide to Mastering This Common Grammar Dilemma

Healing from Being Scarred

While being scarred implies permanence, it does not mean that healing, growth, and integration are impossible. A scar, by its very definition, is evidence that a wound has healed. The injury has closed. The goal of healing from emotional or psychological scars is not to erase them—as that is often impossible—but to reduce their power over your present life and to integrate their story into who you are without letting them define you entirely. The scar remains, but it no longer causes constant pain or dictates your every move.

The journey of healing often begins with acknowledgment. This means recognizing and accepting that you have been scarred by an event, rather than dismissing it or telling yourself to “just get over it.” The next, and perhaps most crucial step, is processing the trauma. This is often best done with the guidance of a mental health professional. Therapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and trauma-focused therapies are specifically designed to help the brain properly process and integrate traumatic memories. They help to move the memory from a place of raw, re-lived terror to a place of historical narrative. The event becomes something that happened to you, not something that is continuously happening.

Building a robust support system is another pillar of healing. Connecting with trusted friends, family, or support groups can provide validation and reduce the feelings of isolation that often accompany trauma. Furthermore, developing healthy coping mechanisms—such as mindfulness, meditation, journaling, and physical exercise—can help regulate the nervous system and manage the symptoms of anxiety and hypervigilance that scars can produce. Healing is not a linear process, and it looks different for everyone. The objective is to transform the scar from an open wound that dictates your life into a part of your history that you have made peace with, a testament to your resilience and capacity for survival.

A Side-by-Side Comparison

To crystallize the distinctions we’ve discussed, the following table provides a clear, side-by-side comparison of “scared” versus “scarred” across several key categories.

| Feature | Scared | Scarred |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Definition | A temporary emotional state of fear. | A permanent mark, physical or emotional, from a past wound. |

| Part of Speech | Primarily an adjective (e.g., I feel scared). | Primarily an adjective from a past participle (e.g., I am scarred). |

| Nature | Transient, fleeting, momentary. | Lasting, enduring, permanent. |

| Cause | A perceived immediate threat or danger. | A physical injury or psychological trauma. |

| Effect | Fight, flight, or freeze response; adrenaline rush. | A lasting change in behavior, outlook, or physical appearance. |

| Example | “The loud thunder made the dog scared.” | “The surgery left a faint scar on her knee.” |

| Psychological Context | A normal, adaptive fear response. | Often associated with trauma, PTSD, or deep emotional wounds. |

| Common Phrases | Scared to death, scaredy-cat, scared stiff. | Scarred for life, emotionally scarred, battle-scarred. |

In a Nutshell

In the final analysis, the difference between scared and scarred is the difference between a passing cloud and a geological feature. One is a weather pattern in your emotional sky—intense, sometimes dramatic, but always moving on. The other is a canyon carved by a river of pain, a permanent part of your landscape. You can be scared without becoming scarred, but the most profound scars often begin with a state of utter, overwhelming fear. Understanding this distinction is a act of linguistic precision and, more importantly, an act of emotional intelligence. It allows us to communicate our own experiences with greater accuracy and to listen to the stories of others with deeper empathy, recognizing the fleeting alarms from the lasting monuments to survival.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main grammatical difference between scared and scarred?

The main grammatical difference lies in their core usage. “Scared” is primarily an adjective describing a temporary state of fear, as in “I am scared of the dark.” It can also be the past tense of the verb “to scare,” as in “The movie scared me.” “Scarred,” on the other hand, is an adjective derived from the past participle of the verb “to scar.” It describes a permanent condition resulting from a past action, as in “He was scarred by the accident.” You are scared in the moment, but you have been scarred by a past event.

Can a person be both scared and scarred at the same time?

Absolutely. In fact, this is often the case when a past trauma is triggered. A combat veteran with PTSD (and therefore psychologically scarred) may feel intensely scared—experiencing the same physiological fear response—when they hear a loud noise that reminds them of gunfire. The scar is the lasting vulnerability and the altered nervous system; the fear is the immediate, relived experience triggered by a present-day stimulus. The scar makes them more susceptible to being scared in specific situations.

How can I remember the difference between scared and scarred?

A simple and effective mnemonic is to link the spelling to the meaning. Remember that “scarred” has a double ‘r’, just like the word “error” or “horror.” A scar is often the result of a physical error or a horrifying event. Alternatively, think of a physical “scar,” which is a mark. The word “scarred” contains the word “scar,” making it easy to remember that it relates to a lasting mark. “Scared,” with its single ‘r’, is related to a fleeting feeling, which has fewer letters and is thus less “weighty.”

Is it possible to be scarred without a major traumatic event?

While major trauma often leads to significant scarring, what is traumatic for one person may not be for another. The definition of trauma is subjective and depends on the individual’s perception and resources. A seemingly less severe event, if it makes a person feel trapped, helpless, or utterly terrified, can indeed leave a psychological scar, especially if it occurs during childhood or if the person lacks a supportive environment to process it. The intensity of the scar is related less to the objective “size” of the event and more to its subjective impact on the individual.

If a scar is permanent, does that mean there’s no hope for healing?

Not at all. This is a critical distinction. Healing from being scarred does not mean the scar disappears. In the physical world, a healed wound still has a scar. The pain of the original injury is gone, and the wound is closed, but the mark remains. Similarly, emotional and psychological healing means the traumatic event no longer controls your life or causes active, daily suffering. The memory may still be there, and the scar may be visible, but it is integrated. You have learned to live with it, and it no longer holds the same debilitating power over you. Healing is about reclaiming your life from the scar, not erasing it.

Conclusion

The journey through the meanings of “scared” and “scarred” is a journey through the geography of human experience. We all encounter moments that leave us scared—it is an unavoidable and necessary part of being alive, a system that protects us from danger. But for some, those moments cross a threshold, leaving behind scars that tell a story of pain, survival, and resilience. Understanding the difference is more than an academic exercise; it is a tool for compassion. It allows us to honor our own stories and the stories of others with greater clarity. It teaches us that while we cannot always avoid the events that scare us, we have a profound capacity to heal from the wounds that scar us, carrying our marks not as open sores, but as testaments to the strength it took to mend. Let your fleeting fears pass like weather, and treat your lasting scars with the respect and care they deserve, for they are part of the map that shows where you have been and how far you have come.

Quotes:

“Fear is a reaction. Courage is a decision.” – Winston S. Churchill. This quote highlights the temporary nature of being scared (a reaction) and the lasting quality of the character built in response to it, which can prevent a fearful moment from becoming a permanent scar.

“The wounds that never heal can only be mourned alone.” – Jodi Picoult. This speaks directly to the experience of being scarred, acknowledging the deep and lasting pain that some traumas inflict.

“The world breaks everyone, and afterward, some are strong at the broken places.” – Ernest Hemingway. This powerful statement encapsulates the entire process. We are all scared and wounded by the world (potentially scarred), but healing can integrate those scars, making us stronger.

“Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear—not absence of fear.” – Mark Twain. This reminds us that being scared is universal, but it is our relationship with that fear that determines whether it masters us or we master it, influencing whether it becomes a debilitating scar.