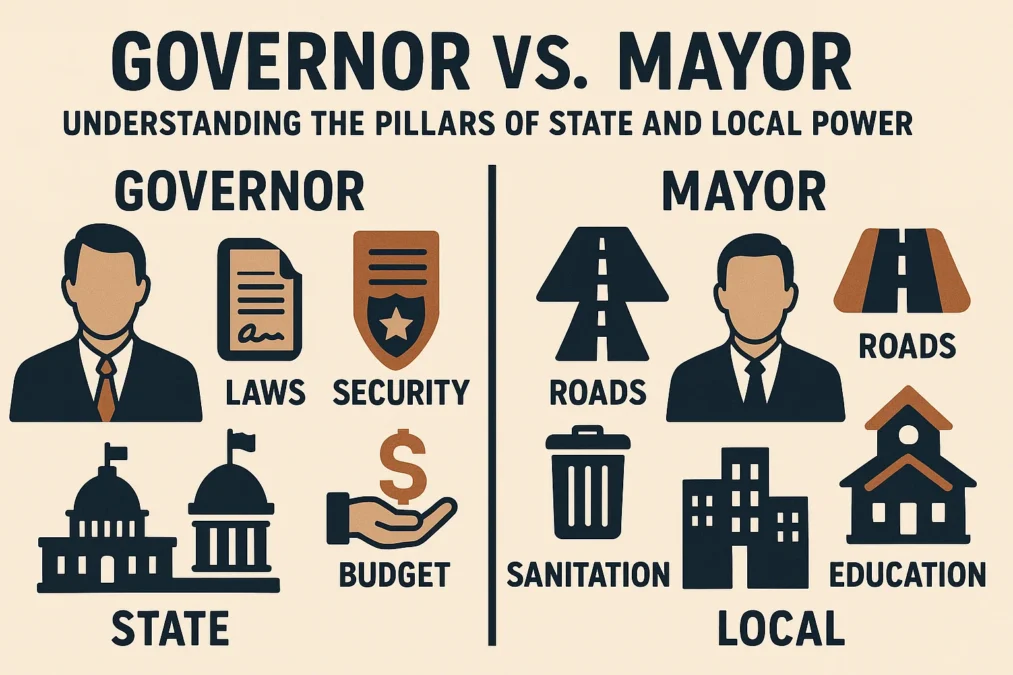

Governor vs Mayor: In the complex tapestry of American government, two figures stand as the most recognizable faces of executive authority: the governor and the mayor. We see their names on ballots, their faces on the news, and their signatures on everything from sweeping state laws to local park regulations. But for many citizens, the line between these two powerful roles can seem blurry. Is a mayor just a mini-governor for a city? Does a governor wield the same kind of power on a state level that the President does on a federal one? Understanding the distinction is more than a civics lesson; it’s key to knowing who to hold accountable for the issues that affect our daily lives, from the quality of the roads we drive on to the funding for our children’s schools.

This deep dive will unravel the intricate layers of responsibility, power, and influence that define the offices of governor and mayor. We will explore the constitutional foundations that grant them authority, the vast scope of their daily duties, and the unique challenges each leader faces. While both are chief executives tasked with managing a government, administering a budget, and serving their constituents, the scale, scope, and nature of their power differ dramatically. By the end of this article, you will have a clear, comprehensive understanding of how a governor steering a state of millions compares to a mayor revitalizing a single city, and why both are indispensable to the functioning of American democracy.

The Foundation of Their Power

Where a leader derives their authority fundamentally shapes how they can use it. The governor and the mayor operate from distinct legal and jurisdictional bases, which sets the stage for all their subsequent actions and responsibilities. Think of it as the difference between being the CEO of a massive, diverse multinational corporation and being the CEO of a dynamic, focused subsidiary. Both are in charge, but their charters, their boards of directors, and their market scopes are entirely different. This foundational disparity influences everything from their legislative relationships to their ability to respond in a crisis.

A governor‘s power is primarily rooted in the state constitution. Each of the fifty states has its own constitution, a document that outlines the structure of state government and explicitly enumerates the powers of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. This makes the governor a constitutionally established officer, with a broad mandate over an entire state. Their authority is recognized across all the cities, counties, and towns within their state’s borders. In contrast, a mayor‘s power is typically derived from the city charter. This charter is like a constitution for the municipality, but it is often granted by the state government, making cities legally “creatures of the state.” This means the fundamental powers of a mayor can be more easily altered or even revoked by the state legislature, a dynamic that can sometimes lead to tension between city halls and state capitols.

The Governor: Chief Executive of the State

The office of the governor is one of immense prestige and responsibility, often considered a stepping stone to the presidency. As the head of the state government, a governor is responsible for the well-being of millions of people across a vast and often geographically and politically diverse territory. Their role is multifaceted, blending the duties of a chief executive, a commander-in-chief, a legislative leader, and a national figure. When we think about the laws that affect state taxes, the management of massive highway systems, or the response to a statewide natural disaster, we are looking at the world of the governor. Their decisions can shape a state’s economic destiny for decades and influence the national political conversation.

The day-to-day life of a governor is a relentless cycle of high-stakes decision-making. They are responsible for proposing a state budget that can amount to hundreds of billions of dollars, a document that reflects their priorities for education, healthcare, infrastructure, and public safety. They appoint the heads of critical state agencies, from the department of transportation to the state police, effectively setting the tone and direction for the entire state bureaucracy. Furthermore, the governor serves as the commander-in-chief of the state’s National Guard, a power that becomes critically important during emergencies like hurricanes, wildfires, or civil unrest. This combination of fiscal, administrative, and military authority makes the governor‘s office the central pillar of state-level power.

The Mayor: Chief Executive of the City

If the governor is the CEO of the state, the mayor is the CEO of the city. This role is intensely focused on the immediate, tangible realities of urban life. While a governor deals in broad policy and macro-level management, a mayor is concerned with the services that citizens interact with every single day. The quality of the public schools, the efficiency of garbage collection, the safety of the neighborhoods, the maintenance of local parks, and the smooth flow of traffic are all ultimately the mayor‘s responsibility. This proximity to the electorate makes the mayor‘s job uniquely personal and immediately accountable; you are far more likely to meet your mayor at a local grocery store than you are your governor.

The scope of a mayor‘s power, however, is not uniform. It varies dramatically depending on the structure of the city government, primarily falling into two models: the “strong-mayor” and “weak-mayor” systems. In a strong-mayor system, the mayor is a true chief executive, with the power to veto legislation passed by the city council, draft the city budget, and hire and fire department heads like the police chief and the fire chief. In a weak-mayor system, power is more diluted. The mayor may be merely a presiding officer of the city council with limited veto power or no veto power at all, and much of the administrative authority rests with the council or a hired city manager. This means the title of “mayor” can represent vastly different levels of actual executive power from one city to the next.

Key Differences in Responsibilities and Duties

While both roles involve leadership and management, the specific responsibilities of a governor and a mayor highlight the stark contrast between state and local governance. A governor‘s portfolio is expansive, covering areas that are inherently statewide or national in character. They are the chief diplomat for the state, often leading trade missions to other countries to attract business and investment. They oversee a state prison system, a massive undertaking involving thousands of inmates and staff. The governor is also responsible for signing or vetoing bills that can change the entire legal landscape of the state, from abortion access to gun laws to environmental regulations.

The mayor‘s duties, by comparison, are hyper-local. Their focus is on the infrastructure and quality of life within a specific municipal boundary. A mayor works on issues like zoning laws, which dictate how land can be used for residential, commercial, or industrial purposes. They are directly accountable for the performance of the city’s police and fire departments. They oversee the public school system in many major cities and are tasked with managing affordable housing crises, public transportation networks, and local economic development projects. When a pothole needs filling or a new public library is being built, it is the city government, under the mayor‘s leadership, that citizens look to for action and answers.

Budgetary Power and Fiscal Management

The power of the purse is one of the most significant tools any executive possesses, and here, the scale of a governor‘s responsibility dwarfs that of even the most powerful mayor. A state budget is a behemoth, often the largest financial document in the state. Governors propose and negotiate budgets that fund entire public university systems, statewide healthcare programs like Medicaid, sprawling interstate highway networks, and the state’s share of K-12 education funding. These budgets are in the tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars, and the battles over them with the state legislature can shut down the government if a compromise is not reached.

A city budget, managed by the mayor and city council, is focused on municipal services. It funds the salaries of police officers, firefighters, and sanitation workers. It allocates money for repaving streets, maintaining parks, running public libraries, and supporting local community centers. While these budgets can be substantial—reaching into the billions for large cities like New York or Los Angeles—they are inherently more limited in scope. Furthermore, a mayor‘s financial autonomy is often constrained by the state. States can place caps on property tax rates, which are a primary source of city revenue, and can mandate that cities provide certain services without providing the funding for them, a practice known as an unfunded mandate.

GMAT vs GRE: The Ultimate Guide to Choosing Your Business School Entrance Exam

Commander-in-Chief and Public Safety Roles

The public safety responsibilities of a governor and a mayor differ significantly in scale and nature, particularly regarding the use of force. The governor serves as the official commander-in-chief of the state’s National Guard. This is a formidable power. The National Guard can be deployed by a governor to assist in disaster response, such as providing aid after a flood or earthquake, or to quell large-scale civil disturbances that overwhelm local police forces. In times of extreme crisis, the governor has the authority to declare a state of emergency, which unlocks special powers and access to federal resources.

A mayor, on the other hand, is the top civilian leader over the city’s police department. Their role is to set public safety policy, support the police chief, and be the public face of law and order for the community. While a mayor does not have a military force at their disposal, they are on the front lines of community policing issues. They must navigate complex relationships between the police and the communities they serve, address concerns about crime rates, and manage the city’s 911 emergency response system. In a crisis, the mayor is often the first leader on the scene, coordinating the local response until state resources, potentially including the National Guard activated by the governor, can be brought to bear.

The Legislative Dynamic

No executive operates in a vacuum, and the relationships that a governor and a mayor have with their respective legislative bodies are crucial to their success. A governor works with a state legislature—a bicameral body comprising a State House of Representatives and a State Senate, mirroring the federal Congress. This relationship is a constant dance of negotiation, persuasion, and sometimes confrontation. The governor‘s most potent legislative tool is typically the veto, which can only be overridden by a supermajority vote in the legislature. This gives the governor significant leverage in shaping legislation.

A mayor‘s legislative counterpart is the city council, a much smaller body focused exclusively on municipal affairs. The dynamics here are intensely local and personal. In a strong-mayor system, the mayor may have a powerful veto, but because the council is smaller, each individual council member’s vote carries more weight, and political alliances can be fragile. In a council-manager system or a weak-mayor system, the mayor may have little to no formal legislative power, acting more as a consensus-builder or a ceremonial figurehead. The mayor must often work more closely and constantly with the council than a governor does with a sprawling, often partisan state legislature.

Jurisdiction and Geographic Scope

The geographic scope of authority is one of the most straightforward differentiators between a governor and a mayor. A governor‘s jurisdiction is the entire state. This includes not only its major cities but also its suburbs, small towns, rural counties, and unincorporated territories. This means a governor must craft policies that are intended to work for a incredibly diverse set of communities, from dense urban centers to sparsely populated agricultural areas. A policy that benefits a major port city might be detrimental to a farming community, and the governor must navigate these conflicting interests.

A mayor‘s jurisdiction is strictly limited to the incorporated boundaries of their city. Their authority ends at the city limit sign. This creates a unique challenge: many of the issues facing a city, such as traffic, economic development, and housing, are regional in nature. A mayor must often collaborate with the mayors of neighboring cities and county officials to address problems that spill over arbitrary political boundaries. This limited geographic scope means a mayor‘s power is concentrated but also inherently constrained, requiring a different kind of diplomatic skill to achieve regional cooperation.

Path to Office and Political Trajectory

The journey to becoming a governor is typically different from the path to becoming a mayor, and the offices often serve as springboards to different political futures. A governor almost always has a long history in politics, having often served in the state legislature, as the state’s attorney general, or as a high-profile executive in another field. Gubernatorial campaigns are massive, expensive statewide affairs that require building a broad coalition of voters. Success in this role is historically one of the strongest credentials for a presidential run, as it demonstrates executive experience managing a large, complex government.

The path for a mayor can be more varied. Some mayors rise through the ranks of the city council or local community boards, while others are prominent local business leaders or activists who leap into politics. A mayoral campaign is a grassroots-intensive effort, focused on winning the votes of a specific community. While being a big-city mayor can lead to a national profile—figures like New York’s mayor or Chicago’s mayor are often in the national news—the trajectory more commonly leads to a career focused on local or regional issues, or a jump to a state-level position, rather than a direct path to the presidency.

A Tale of Two Crises

Examining how a governor and a mayor handle the same type of crisis reveals the fundamental differences in their roles and resources. Let’s take the example of a major hurricane making landfall. The governor operates as the strategic commander. They declare a statewide state of emergency, activate thousands of National Guard troops, coordinate with FEMA for federal assistance, and issue mandatory evacuation orders for entire coastal regions. Their press conferences are broadcast statewide, providing critical information and resources to a massive audience.

The mayor of a coastal city in the hurricane’s path, meanwhile, is the tactical commander on the ground. They are responsible for executing the governor‘s evacuation orders within their city, directing the local police to manage traffic flow, opening and managing local shelters in schools and community centers, and ensuring that first responders are prepared for rescue operations. After the storm, the mayor is the one coordinating the initial damage assessment, the clearing of city streets, and the restoration of local power and water, while the governor manages the larger recovery effort and distributes state and federal funds. Both are essential, but their spheres of action are distinct yet interconnected.

The Evolving Roles in Modern Politics

The traditional boundaries between state and local authority are becoming increasingly fluid, and the roles of governor and mayor are evolving in response. In an era of federal gridlock, many states have become “laboratories of democracy,” with governors taking the lead on contentious issues like climate change, immigration, and cannabis legalization. This has elevated the political stature of governors and increased the stakes of gubernatorial elections, drawing more national money and attention.

Simultaneously, many mayors have stepped onto the national stage by taking bold stances on issues that the federal or state governments have failed to address. We see “sanctuary cities” where mayors set local law enforcement policies that contradict state or federal immigration directives. We see mayors forming national coalitions to uphold the Paris Climate Accord or to advocate for gun control. This has created a new dynamic where a mayor can act as a powerful check on a governor or even a president, using the city as a platform for a national political movement and asserting a degree of autonomy that challenges the traditional hierarchy of American federalism.

Choosing a Path of Service

Ultimately, whether an individual aspires to be a governor or a mayor often reflects their preferred scale of impact and type of work. A person drawn to broad, systemic policy, who thinks in terms of macroeconomics, statewide systems, and national trends, may be more suited to the role of governor. It is a job of vision, strategy, and managing immense, sprawling bureaucracies. The governor is often several steps removed from the individual citizen, but their policies touch every life in the state in profound ways.

Conversely, a person who thrives on immediate, tangible results and deep community engagement may find their calling as a mayor. The mayor‘s work is about the here and now—fixing a broken streetlight, supporting a local business, celebrating a neighborhood festival. The feedback is direct and immediate. While the mayor may not command armies or sign multi-billion-dollar budgets for university systems, their impact on the daily lived experience of their constituents is arguably more direct and personal than that of any other elected official in the American system.

Conclusion

The American system of government is a multi-layered ecosystem, and the governor and the mayor serve as the chief executives of two of its most critical layers. The governor is the strategist, the state-wide leader navigating the complexities of a diverse population and a massive economy, wielding powers that echo those of a president. The mayor is the tactician, the community leader immersed in the daily grind of urban life, turning policy into pavement and promises into public services. One is not inherently more important than the other; they are complementary forces. Understanding the distinction between a governor vs mayor—their sources of power, their responsibilities, and their constraints—empowers us as citizens. It allows us to know who to call, who to praise, and who to hold accountable for the myriad issues that shape our communities and our states, ensuring that our democracy remains responsive and vibrant from the city hall to the state capitol.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between a governor and a mayor?

The main difference boils down to jurisdiction and scope. A governor is the chief executive of an entire state, with authority over millions of people across cities, towns, and rural areas. Their responsibilities include state budgets, signing state laws, and commanding the National Guard. A mayor is the chief executive of a single city or municipality, focused on local issues like police and fire services, public schools, road maintenance, and local zoning laws. The governor operates on a macro, strategic level, while the mayor operates on a micro, tactical level.

Can a mayor become a governor?

Absolutely. It is a common career path in American politics. Serving as a mayor, especially of a large and prominent city, provides valuable executive experience in managing a budget, overseeing agencies, and dealing with public crises. This experience is often seen as excellent preparation for the larger-scale challenges of being a governor. Many successful governors, such as New York’s Andrew Cuomo (who was previously HUD Secretary but whose political profile was built in part on his father’s legacy as governor) or California’s Gavin Newsom, first served as mayors of major cities (in Newsom’s case, San Francisco).

Who has more power, a governor or a mayor?

In terms of the sheer scale of legal authority, budgetary control, and jurisdictional reach, a governor almost always has more formal power than a mayor. A governor presides over a much larger government, a bigger budget, and has command of the National Guard. However, the power of a mayor can be significant, especially in a “strong-mayor” system governing a massive city like New York or Chicago. In such cases, the mayor‘s influence on national culture and policy can sometimes rival that of a governor from a smaller state, but legally and structurally, the governor‘s powers are broader and more profound.

Do governors and mayors work together?

They must. The relationship between a governor and a mayor is crucial, though it can sometimes be contentious. They collaborate on issues like transportation funding, disaster response, and economic development projects that benefit both the city and the state. For example, a mayor might need state funding from the governor‘s budget to expand a public transit system, or a governor might rely on a mayor to effectively implement a statewide public health initiative at the local level. When this relationship is cooperative, it can lead to great success; when it is adversarial, it can result in political gridlock that harms citizens.

How does the power of a mayor in a “strong-mayor” city compare to a “weak-mayor” city?

The difference is night and day. In a “strong-mayor” system, the mayor is a true chief executive with significant powers, including the ability to veto legislation from the city council, appoint and dismiss department heads, and craft the city budget with substantial independence. This is the model used in most large American cities. In a “weak-mayor” system, the mayor has limited formal power, often serving as a mere chairperson of the city council with little or no veto authority. In these systems, most of the executive power is vested in the city council as a whole or in a professionally trained city manager who is appointed to run the day-to-day operations of the government.

Comparison Table: Governor vs Mayor at a Glance

| Feature | Governor | Mayor |

|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | Entire State | A Single City/Municipality |

| Source of Power | State Constitution | City Charter (granted by the state) |

| Primary Responsibilities | State budget, state laws, prisons, universities, National Guard, interstate commerce. | Police & fire, local schools, roads, parks, sanitation, zoning, local taxes. |

| Legislative Body | State Legislature (House & Senate) | City Council |

| Budget Scale | Very Large (Tens to Hundreds of Billions) | Smaller, but can be large in big cities (Billions) |

| Military Role | Commander-in-Chief of State National Guard | Civilian oversight of City Police Department |

| Typical Veto Power | Yes, often strong | Varies (Yes in Strong-Mayor, No in Weak-Mayor) |

| Geographic Focus | Statewide, diverse communities | Hyper-local, within city boundaries |

Quotes on Leadership and Governance

“A governor has to be able to do two things simultaneously. He has to be able to dream great dreams and see the big picture, and he has to be able to count the paper clips.” – George Busbee, former Governor of Georgia

“The mayor is the person who is ultimately accountable for the performance of the city. If you don’t like the potholes, you call the mayor. If you don’t like the taxes, you call the mayor.” – Michael Bloomberg, former Mayor of New York City

“The difference between a governor and a mayor is often the difference between designing the blueprint and laying the bricks. One envisions the structure for an entire region, while the other builds the community where people actually live.” – Anonymous Political Scientist