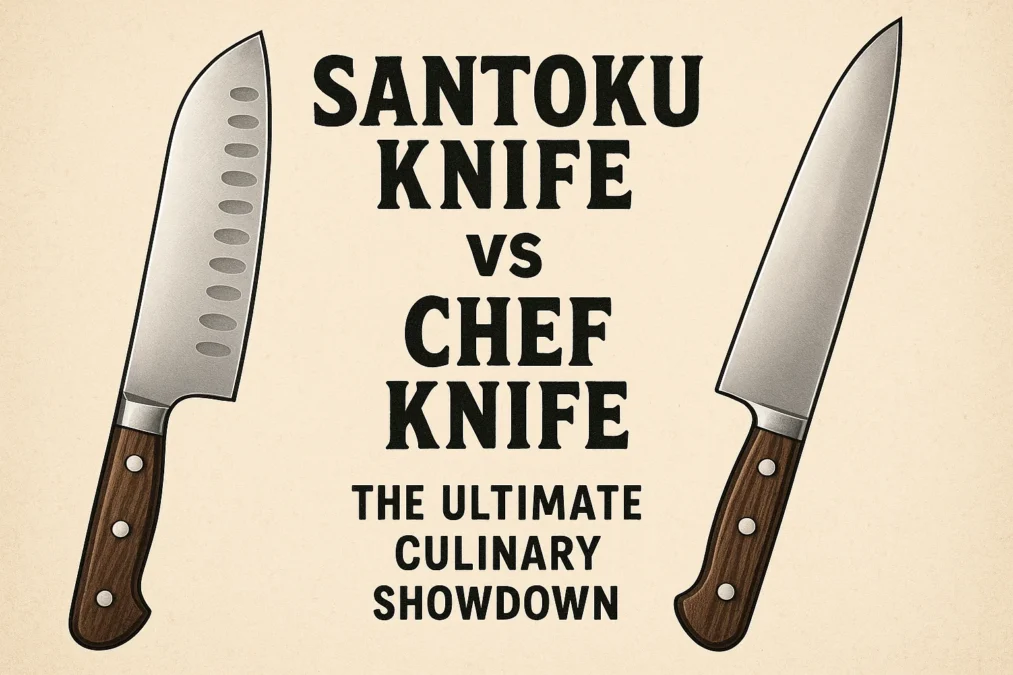

You’re standing in your kitchen, a pile of vegetables waiting on the cutting board, and you reach for your go-to knife. For many home cooks and professional chefs alike, that trusty blade is either a Western-style chef knife or a Japanese-inspired santoku. These two knives are the workhorses of the culinary world, the undisputed champions of the knife block. But what truly sets them apart? Is one objectively better than the other, or do they simply excel in different arenas?

The debate of santoku knife vs chef knife is more than just a matter of East versus West; it’s about geometry, balance, and philosophy. The chef knife, with its iconic curved belly, is designed for a rhythmic rocking motion. The santoku, with its flat profile and sheep’s foot blade, is a master of the straight, up-and-down chop. Choosing between them isn’t about finding the “best” knife, but about finding the best knife for you—for your cutting style, the food you cook most, and what feels like a natural extension of your own hand. This comprehensive guide will dive deep into the history, design, and performance of these two kitchen legends, giving you all the knowledge you need to make an informed decision and perhaps even discover your new favorite tool.

A Tale of Two Blades: Unpacking the Histories

To understand why these knives are the way they are, we have to look back at the cultures that created them. The story of the chef knife and the santoku is a story of different ingredients, different cooking traditions, and different approaches to the very act of cutting.

The Western chef knife, as we know it today, is a descendant of the French chef’s knife, which evolved from a variety of butchery and kitchen tools in 19th century Europe. Its design was heavily influenced by French cuisine, which often features a mirepoix—a finely diced mix of onions, carrots, and celery—as a base for countless dishes. The rocking motion, perfectly facilitated by the chef knife’s curved blade, is an incredibly efficient way to quickly and uniformly reduce these vegetables to a small dice. This knife was also built to handle a wider variety of tasks, from disjointing large cuts of meat to finely mincing herbs, making it the true “all-purpose” tool for European chefs working with a diverse set of proteins and produce.

The santoku, on the other hand, has a much more recent and specific origin. Its name, 三德, translates to “three virtues” or “three uses,” commonly interpreted as slicing, dicing, and mincing. It emerged in Japan in the mid-20th century as a hybrid design, influenced by the traditional Japanese gyuto (which is itself the Japanese version of the chef knife) and older Japanese vegetable knives. Japanese cuisine places a tremendous emphasis on precision, aesthetics, and the integrity of ingredients. Cutting is not just a means to an end; it’s a step that can affect the texture, flavor, and appearance of the final dish. The santoku’s design reflects this philosophy, favoring clean, straight cuts that cause less bruising to delicate herbs and vegetables, and creating beautifully uniform slices for presentation.

The Anatomy of a Champion: Breaking Down the Design

When you place a santoku and a chef knife side-by-side, the differences become immediately apparent. Each element of their design, from the tip to the heel, serves a specific purpose and informs how the knife is meant to be used. Let’s dissect them piece by piece.

The most striking difference is the blade profile. A classic chef knife features a significant curve along its cutting edge, sweeping upward to a distinct, pointed tip. This curve is the engine of the rocking motion. As you rock the knife back and forth, the entire blade maintains contact with the cutting board, allowing for rapid, continuous chopping. The pointed tip is also incredibly useful for detailed work, like coring a tomato or scoring dough. In contrast, the santoku boasts a much flatter profile with a blunted, dropped spine that forms what’s known as a “sheep’s foot” tip. This flat edge is designed for a straight, guillotine-like chop, where the knife is lifted straight up and brought straight down. This motion is excellent for producing clean, consistent slices and is often seen as easier for beginners to control.

Another critical distinction lies in the grind, or the cross-sectional geometry of the blade. Western chef knives typically have a double-bevel edge, meaning both sides of the blade are sharpened at a symmetrical angle, usually around 20 degrees per side. This creates a robust, durable edge that can handle a wider range of tasks, including chopping through small bones in chicken or cutting through tougher winter squashes. Many Japanese santokus, while also double-bevel, are often sharpened to a more acute angle, sometimes as low as 12-15 degrees per side. This creates an incredibly sharp edge that slices through food with less resistance, but it can also be more delicate and prone to chipping if used on hard ingredients. Furthermore, santokus often feature a distinct hollow grind, or granton edge, which are the iconic oval-shaped divots on the side of the blade. These air pockets are designed to reduce friction and prevent food, particularly starchy vegetables like potatoes, from sticking to the blade.

The Feel in Your Hand: Ergonomics and Balance

A knife can have perfect geometry on paper, but if it feels wrong in your hand, it’s the wrong knife for you. The ergonomics and balance of the santoku and chef knife are tailored to their intended use and, by extension, to different user preferences.

A standard chef knife, usually ranging from 8 to 10 inches in length, is designed with a heel that provides ample clearance for your knuckles. This is known as a good “knuckle clearance.” When you grip the knife in a professional pinch grip (with your thumb and forefinger pinching the blade just in front of the handle), the height of the blade ensures your knuckles won’t scrape against the cutting board as you rock. The balance point of a chef knife is typically forward, near the point where the blade meets the handle. This gives the knife a slight head-heavy feel, which can be advantageous for tasks that require a bit of force, as the weight of the blade helps do the work for you.

The santoku is generally a shorter and lighter knife, commonly found in 5 to 7 inch lengths. Its blade is also taller, but its overall lighter weight and more neutral balance point make it feel incredibly nimble and maneuverable. Many users find the santoku to be less wrist-intensive, as the chopping motion relies less on a continuous rocking of the wrist and more on a simpler up-and-down movement from the elbow. The handle design can also differ, with Western chef knives often featuring a more pronounced, ergonomic handle, while santokus may have a lighter, more neutral Japanese-style handle, like a D-shaped or octagonal wa handle, which encourages a precise and gentle grip.

Putting Them to the Test: Performance in Real-World Tasks

Theory and design are one thing, but how do these knives actually perform when faced with a pile of onions, a clove of garlic, or a whole chicken? Let’s see how each knife handles common kitchen tasks.

When it comes to vegetable prep, the strengths of each knife shine. The santoku is a vegetable-destroying machine. Its flat blade and sharp edge excel at producing perfect, paper-thin slices of cucumber or tomato. The straight edge makes it easier to make full-length cuts through large vegetables like cabbages or eggplants without a rocking motion. Dicing an onion with a santoku is a different experience; instead of the classic rocking method, you’ll use a series of straight vertical chops, which many find leads to cleaner, less crushed results. The chef knife, however, is no slouch with vegetables. Its rocking motion is unparalleled for quickly mincing a large quantity of herbs or creating a fine dice from a pile of carrots and celery. The pointed tip is also invaluable for tasks like de-seeding a pepper or making precise cuts.

The roles start to reverse when we look at meat and fish. The chef knife is the more versatile tool for butchery. Its curved belly and robust edge are perfect for disjointing a chicken, trimming fat from a steak, or chopping through soft bones. The rocking motion can also be used to quickly mince ground meat. The santoku can certainly slice boneless meats, fish, and poultry with incredible precision—its sharp edge is wonderful for slicing raw fish for sashimi or carving a cooked roast into perfect, even slices. However, it is not designed for any kind of heavy butchering work. Using a santoku to cut through bones or frozen food is a surefire way to damage its finer, more delicate edge.

Making the Choice: Which Knife is Right for Your Kitchen?

So, after all this analysis, which one should you choose? The answer, as with most things in the kitchen, is “it depends.” Your decision should be guided by your personal cooking style, the types of food you prepare most often, and what feels most comfortable and intuitive to you.

You might lean towards the classic chef knife if your cooking is diverse and hearty. If you frequently find yourself breaking down whole chickens, chopping through winter squash, rocking through piles of aromatic vegetables for a soffritto, or mincing large quantities of herbs, the chef knife is your steadfast companion. Its versatility and durability make it ideal for the “everything but the kitchen sink” approach to cooking. It’s a powerful, confident tool that can handle a bit of rough treatment and is built for a dynamic, physical cutting style. Many professional kitchens in the West rely on the chef knife for this very reason—it’s a true all-rounder.

The santoku knife might be your perfect match if your culinary focus leans towards precision, vegetables, and boneless proteins. If you cook a lot of vegetarian or Asian-inspired dishes, value beautifully uniform slices for presentation, and prefer a straight chopping motion over a rocking one, the santoku will feel like a dream. Its lightweight and nimble character is excellent for cooks with smaller hands or those who suffer from wrist pain, as it requires less repetitive rocking motion. It’s the knife you reach for when finesse is more important than brute force, perfect for creating delicate salads, stir-fries, and beautifully plated dishes.

Beyond the Binary: Do You Really Need Both?

For the home cook who is passionate about their tools, this isn’t necessarily an either-or proposition. Many seasoned cooks own and regularly use both a chef knife and a santoku, appreciating the unique strengths each one brings to different tasks. It’s like having both a sturdy SUV and a nimble sports car; each is perfect for a different kind of journey.

Having both knives allows you to specialize. You can reserve your robust chef knife for the heavy-duty tasks: breaking down poultry, chopping hard root vegetables, and any job that requires a rocking motion. Meanwhile, your razor-sharp santoku can be your dedicated tool for precision work: slicing soft tomatoes, julienning herbs, dicing onions with minimal tear-inducing crushing, and preparing sushi-grade fish. This practice of using the right tool for the job not only makes your prep work more efficient and enjoyable but also helps preserve the edge and longevity of each knife. There’s no rule that says you must pledge allegiance to only one. Embracing both the power of the West and the precision of the East can make you a more versatile and capable cook.

Carbon vs Stainless Steel: The Ultimate Showdown for Your Tools, Knives, and Projects

The Companion Blades: Understanding Your Knife Set

No knife exists in a vacuum. Both the Western chef knife and the Japanese santoku are the central pillars of their respective knife ecosystems, supported by a set of specialized companion blades. Understanding these can further clarify the role of your primary knife.

In a classic Western knife set, the chef knife is supported by a paring knife for intricate, in-hand work, and a long, flexible serrated knife for slicing bread. A boning knife for detailed butchery and a long slicing knife for roasts are also common. The chef knife is the generalist, designed to cover about 90% of tasks, while the other knives handle the specialized 10%. In a Japanese kitchen, the santoku might be accompanied by a nakiri (a dedicated rectangular vegetable knife), a deba (a heavy, single-bevel knife for breaking down fish), and a yanagiba (a long, single-bevel knife for slicing sashimi). The santoku often serves as a more general-purpose alternative to the highly specialized single-bevel knives, making it a fantastic bridge between Eastern specialization and Western versatility for the home cook.

Caring for Your Investment: Sharpening and Maintenance

Whether you choose a santoku or a chef knife, a sharp knife is a safe and effective knife. However, the maintenance for each can differ slightly due to their edge geometries. Proper care is non-negotiable.

A chef knife with its more durable, double-bevel 20-degree edge can be maintained with a variety of tools, from electric sharpeners to pull-through sharpeners, though most purists would recommend learning to use a whetstone for the best results. Its robust nature is a bit more forgiving of imperfect sharpening techniques. The santoku, with its potentially finer angle, demands more respect. Using a coarse electric sharpener or a pull-through device can easily damage its delicate edge. To maintain its legendary sharpness without causing micro-chips, learning to use a fine-grit whetstone is highly recommended. The technique is the same, but the angle you hold the knife at will be more acute. Regardless of your choice, always hand-wash and immediately dry your knives. The dishwasher is a death sentence for fine edges and beautiful handles, causing corrosion, dulling, and physical damage.

| Feature | Santoku Knife | Chef Knife |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Japan (Mid-20th Century) | Europe (19th Century France/Germany) |

| Meaning of Name | “Three Virtues” (slicing, dicing, mincing) | N/A, denotes its user (the Chef) |

| Typical Length | 5 to 7 inches | 8 to 10 inches |

| Blade Profile | Flat with a sheep’s foot tip | Curved, with a distinct, pointed tip |

| Primary Motion | Straight, up-and-down chop | Rocking motion |

| Best For | Precision slicing, dicing vegetables, boneless proteins | All-purpose tasks, rocking, disjointing poultry |

| Blade Grind | Often a thinner, hollow-ground edge (Granton edges) | Heavier, more robust double-bevel edge |

| Weight & Feel | Lighter, nimble, neutral balance | Heavier, substantial, forward balance |

| Ease of Use | Excellent for beginners due to simple chopping motion | Has a learning curve for the rocking technique |

“The santoku is a scalpel, the chef knife is a cleaver. One is for precision, the other for power. A skilled cook knows when to use which.” – Anonymous Master Chef

“Your knife should feel like an extension of your own hand. If it fights you, it’s the wrong one, no matter how prestigious the brand.” – Culinary Instructor

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main functional difference between a santoku knife and a chef knife?

The main functional difference lies in the cutting motion they are designed for. A chef knife, with its curved blade, is engineered for a fluid rocking motion, making it ideal for quickly mincing herbs or dicing a mirepoix. A santoku knife, with its flatter blade, is designed for a straight, up-and-down chopping motion, which excels at producing clean, uniform slices with less bruising to delicate ingredients. This fundamental difference in design philosophy affects how you interact with your food.

As a beginner, which knife should I buy first, a santoku or a chef knife?

For a complete beginner, many find the santoku knife to be slightly more intuitive initially because the straight chopping motion is easier to master than the rocking motion of a chef knife. Its shorter length and lighter weight can also feel less intimidating and more manageable. However, a classic 8-inch chef knife is arguably more versatile for a one-kitchen-does-all tool, especially if you cook a lot of meat. The best advice is to try to hold both if possible. The one that feels more natural and balanced in your hand is the right one to start with.

Can I use a rocking motion with a santoku knife?

It is not recommended. The santoku’s blade profile is predominantly flat with a dropped tip, which means the curved “belly” necessary for a smooth rock is absent. If you try to rock a santoku, the flat section in the middle will hit the board and interrupt the motion, and you’ll be putting uneven pressure on the edge. This can lead to inconsistent cuts and may eventually damage the blade. The santoku is truly designed for a push-cut or a straight down chop.

Is a santoku knife better for slicing vegetables?

In many cases, yes, the santoku knife is exceptionally good for slicing vegetables. Its flat edge allows for full-length contact with the cutting board, enabling you to slice completely through a carrot or cucumber in one clean, straight-down motion. The thin, sharp blade and often-present Granton edges also help prevent starchy vegetables like potatoes from sticking. This results in beautiful, even slices with less crushing, which is why it’s often preferred for tasks like making a perfect cucumber salad or prepping vegetables for a stir-fry.

Which knife requires more maintenance and sharpening, the santoku or the chef knife?

Typically, a santoku knife may require more frequent honing and careful sharpening. This is because its steel is often harder and its edge is ground to a finer, more acute angle to achieve its legendary sharpness. A harder steel holds an edge longer but can be more brittle and prone to chipping if misused. A Western chef knife, with its softer steel and more durable edge angle, is more forgiving and can often go longer between sharpening sessions, though it will lose its razor edge faster than a santoku under regular use.

Conclusion Santoku Knife vs Chef Knife

The great santoku knife vs chef knife debate doesn’t have a single winner. It culminates in a satisfying truce where both are recognized as masterpieces of culinary tool design, each optimized for a different purpose and preference. The chef knife is the rugged, versatile all-terrain vehicle of the kitchen, built for power, rocking rhythm, and handling a vast array of tasks from butchery to fine mincing. The santoku is the precision sports car—nimble, razor-sharp, and unparalleled in its ability to deliver clean, beautiful cuts with a straightforward, efficient motion.

Your ideal choice ultimately lives in the intersection of your cooking habits, your physical comfort, and your personal philosophy in the kitchen. Do you value robust versatility and a time-tested rocking technique? The chef knife awaits. Do you prioritize lightweight precision, straightforward chopping, and immaculate vegetable prep? The santoku calls your name. The best path forward is to embrace the journey of discovery. Handle both, if you can. Feel their weight, test their balance, and listen to which one feels like a natural extension of your own intention. Whichever champion you welcome into your kitchen, you are gaining a partner that will serve you faithfully for years to come, transforming daily meal preparation from a chore into a craft.