Have you ever tried to put together a complex piece of furniture without looking at the instructions? It’s a frustrating exercise in guesswork. Now, imagine a doctor trying to diagnose a patient, a personal trainer guiding a client, or a yoga instructor explaining a pose without a universal language to describe location. The result would be chaos. This is precisely why anatomists, centuries ago, developed a precise set of directional terms to create a clear, unambiguous map of the human body. At the very heart of this anatomical language lie two fundamental, opposing concepts: anterior vs posterior.

Understanding the distinction between anterior and posterior is like learning the cardinal directions for the human body. It’s the foundational coordinate system that allows healthcare professionals, fitness experts, and students to communicate with incredible accuracy. Whether you’re reading your MRI report, following a workout plan, or simply satisfying your curiosity about how your body is built, grasping this simple “front vs back” dichotomy unlocks a deeper comprehension of human biology. This article will be your comprehensive guide. We will journey through the definitions, explore real-world examples from head to toe, and delve into why this knowledge is crucial in medicine, fitness, and everyday life. By the end, you’ll not only know what these terms mean but you’ll also see the human body through the insightful lens of anatomical precision.

Decoding the Jargon: What Do Anterior and Posterior Actually Mean?

Let’s strip away the complexity and start with the basics. The terms anterior and posterior are Latin in origin, and their meanings are beautifully straightforward. The word anterior derives from the Latin word “ante,” which means “before” or “in front of.” Therefore, in anatomical terms, anterior refers to anything that is toward the front of the body. Think of your eyes, your chest, and your kneecaps—all these structures are situated on the anterior aspect of your body. It’s often used interchangeably with the term “ventral,” especially when discussing quadrupedal animals (those that walk on four legs), but for us bipedal humans, anterior is the preferred term for the front side.

On the flip side, we have posterior. This term comes from the Latin “posterus,” meaning “coming after” or “behind.” Consequently, posterior describes anything that is toward the back of the body. Your shoulder blades, your spine, and your calf muscles are all prime examples of posterior structures. Similar to the anterior-ventral relationship, posterior is synonymous with “dorsal” in the anatomical world. To put it in the simplest possible terms, when you stand in the standard anatomical position—upright, facing forward, arms at your sides with palms forward—everything you can see from the front is anterior, and everything behind you is posterior. This fundamental anterior vs posterior distinction is the first and most critical step in orienting yourself within the body’s landscape.

It’s also crucial to understand that these terms are relative, not absolute. A structure can be described as anterior to another. For instance, your windpipe (trachea) is anterior to your esophagus. This doesn’t just tell you that the windpipe is at the front; it tells you the specific spatial relationship between the two organs. This relational use of anterior and posterior adds a powerful layer of descriptive precision, allowing for a detailed, three-dimensional understanding of how our internal and external parts are arranged. This system eliminates the ambiguity that would come from using casual terms like “behind” or “in front,” which can change based on a person’s orientation. Whether you’re lying down, standing on your head, or doing a handstand, your sternum is always anterior to your spine.

The Standard Anatomical Position: Why It’s the Non-Negotiable Starting Point

Before we can confidently label anything as anterior or posterior, we must all agree on a universal starting point. Imagine two architects trying to design a building without first agreeing on which way is north. Their plans would be incompatible. In human anatomy, the “true north” is known as the standard anatomical position. This is a universally accepted reference posture where the body is standing upright, facing directly forward, with feet parallel and arms hanging at the sides. The critical detail here is that the palms of the hands are facing forward. This specific hand position is what standardizes the entire system.

Why is this so important? Because without this fixed position, the terms anterior and posterior could become confusing. For example, if your arms are relaxed at your sides with your palms facing your thighs, the thumb is positioned more toward the front. But in the standard anatomical position, with palms forward, the thumb is clearly on the lateral side (away from the body’s midline). This consistency ensures that when a physiotherapist in London tells a surgeon in Tokyo that a patient has a tear on the posterior aspect of the left shoulder, there is zero confusion about the exact location being referenced. It creates a common language that transcends individual body movements and positions.

This standardized posture is the bedrock upon which all other directional terms are built. It allows us to describe the body and its structures accurately, regardless of the actual position the body is in at any given moment. Whether a patient is lying face down on an examination table or curled up in a fetal position, medical professionals always mentally visualize the body in the standard anatomical position to communicate clearly. This mental model is what makes the anterior vs posterior distinction so powerful and reliable. It is the unchanging map that guides all navigation through the complex and variable terrain of the human form.

Anterior and Posterior in Action: A Head-to-Toe Tour of the Body

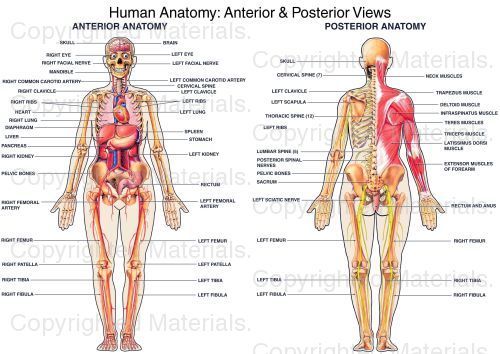

The best way to solidify the anterior vs posterior concept is to take a concrete tour of the body, identifying key structures on both the front and back. This will transform the abstract terms into tangible, recognizable parts of your own anatomy. Starting from the top, the anterior portion of the head includes your face—your forehead, eyes, nose, cheeks, and mouth. The frontal lobe of the brain, responsible for reasoning and voluntary movement, is named for its position near the anterior part of the skull. When you smile, you are using a host of anterior facial muscles.

Conversely, the posterior aspect of the head is the back of your skull. This is where you find the occipital bone, which protects your occipital lobe—the part of the brain dedicated to processing visual information. The back of your neck, with its complex web of muscles that support the weight of your head, is also a posterior structure. This clear anterior vs posterior division continues down the body. Your chest, or thoracic region, is anterior and houses the sternum and pectoral muscles. Your abdomen, with its digestive organs, is on the anterior side, while the back is, by definition, posterior, encompassing the entire spinal column (vertebrae), the scapulae (shoulder blades), and the massive latissimus dorsi and trapezius muscles.

Moving to the limbs, the distinction remains just as clear. Your kneecap, or patella, is a classic anterior landmark of the leg. The shin bone (tibia) is on the anterior side of the lower leg. In contrast, the back of the leg is dominated by the hamstring muscles on the thigh and the calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus) on the lower leg, all of which are posterior. In the arms, the biceps brachii is located on the anterior aspect of the upper arm, while its opposing muscle group, the triceps brachii, is found on the posterior side. This comprehensive head-to-toe survey demonstrates how the anterior vs posterior framework provides a consistent and logical way to describe the location of virtually every part of the human body.

Beyond the Surface: Anterior and Posterior Inside the Body

The utility of the anterior vs posterior framework isn’t limited to what we can see on the surface. It is equally, if not more, critical for describing the location and relationships of our internal organs and structures. Within the skull, for example, the pituitary gland, a master controller of the endocrine system, sits in a bony structure called the sella turcica. Its position is described as being on the anterior aspect of the brain, just beneath the hypothalamus. This precise localization is vital for neurosurgeons planning a delicate operation.

Within the thoracic cavity, the spatial relationships defined by anterior and posterior are essential for understanding anatomy. The heart is not centered in your chest; about two-thirds of it lies to the left of the midline. Its position is described as being anterior to the vertebral column (spine) and posterior to the sternum. The lungs, located on either side of the heart, have distinct lobes with anterior and posterior portions, which is important when listening to breath sounds with a stethoscope. Even the delicate lining of the lungs, the pleura, is divided into layers that cover the anterior, posterior, and lateral surfaces of the lungs and the inner wall of the chest cavity.

This internal mapping extends to the abdomen and pelvis. The stomach is primarily an anterior organ, sitting just below the left side of the diaphragm. The pancreas, however, is a retroperitoneal organ, meaning it lies posterior to the peritoneal cavity, tucked behind the stomach. The kidneys are also posterior structures, located high up against the posterior abdominal wall. Understanding these internal anterior vs posterior relationships is not just academic; it directly impacts medical procedures. For instance, a surgeon performing an appendectomy must navigate through anterior abdominal layers to reach the appendix, while a surgeon accessing a kidney often does so from a posterior or flank approach to avoid the peritoneal cavity altogether.

The Critical Role in Medicine and Healthcare

In the high-stakes world of medicine, clear and precise communication is a matter of patient safety. The anterior vs posterior terminology is woven into the very fabric of clinical practice, from diagnosis and documentation to surgical planning and rehabilitation. When a patient presents with chest pain, a doctor must determine if the pain is originating from the anterior chest wall (like costochondritis), the heart (which lies behind the sternum), or perhaps from a posterior structure like a thoracic vertebra causing referred pain. The precise location, described using these terms, is a critical diagnostic clue.

Medical imaging relies entirely on this language. A radiologist reading an X-ray, CT scan, or MRI will describe findings with exact anterior vs posterior references. A report might state: “There is a consolidation in the posterior segment of the right upper lobe of the lung,” or “A disc herniation is noted at the L4-L5 level, compressing the anterior aspect of the thecal sac.” This precision guides the treating physician directly to the problem. Furthermore, surgical procedures are named and planned using these terms. An anterior cervical discectomy involves approaching the spine from the front of the neck, while a posterior lumbar fusion is performed through the lower back. The choice of approach has significant implications for the surgery’s risks, benefits, and recovery process.

In physical therapy and rehabilitation, the anterior vs posterior concept is fundamental to assessing and treating musculoskeletal imbalances. A common postural issue is “anterior pelvic tilt,” where the front of the pelvis drops forward and the back rises. This posture tightens the anterior hip flexors and weakens the posterior gluteal and abdominal muscles. A physical therapist, recognizing this anterior vs posterior muscle imbalance, will design a stretching and strengthening program that specifically targets the overactive anterior muscles and the underactive posterior muscles to restore proper alignment and function, thereby alleviating pain.

The Fitness and Athletic Perspective: Balancing Your Body

The principles of anterior and posterior are not confined to the clinic; they are absolutely essential in the gym, on the track, and in the yoga studio. A well-designed fitness regimen focuses not just on strength but on balanced strength, and this balance is often framed as a harmony between the anterior and posterior muscle chains. Many people, especially those with sedentary jobs, develop what is known as “anterior dominance.” This means the muscles on the front of their body—chest, shoulders, hip flexors, and quads—become tight and overused, while the posterior chain muscles—upper back, glutes, and hamstrings—become weak and inhibited.

Ignoring this anterior vs posterior imbalance is a recipe for injury and poor performance. A strong posterior chain is the engine for powerful athletic movements like sprinting, jumping, and lifting. It is also crucial for stability and posture. Weak glutes and hamstrings can lead to compensations that strain the knees and lower back. This is why savvy personal trainers and athletes dedicate significant time to posterior chain exercises like deadlifts, hip thrusts, rows, and pull-ups. They are not just building muscle for appearance; they are creating a balanced, resilient, and powerful physique by addressing the critical anterior vs posterior dynamic.

This concept also applies to flexibility and mobility. A comprehensive stretching routine must address both sides of the body. Stretching the anterior hip flexors and quadriceps is as important as stretching the posterior calf muscles and hamstrings. In yoga, many poses are designed to create balance. A heart-opening backbend like Cobra Pose stretches the anterior torso and strengthens the posterior back muscles, while a forward fold provides a deep stretch for the entire posterior chain from the calves to the hamstrings to the back. By consciously working both the anterior and posterior aspects of your body, you promote symmetry, prevent injury, and enhance your overall functional movement.

Related Anatomical Terms: Expanding the Directional Vocabulary

While anterior and posterior provide the crucial front-to-back axis, the anatomical map requires other directional terms to be fully functional. Understanding these related terms provides a more complete picture of spatial relationships in the body. The first pair is medial and lateral. Medial means toward the midline of the body (the imaginary line that runs from the head to the feet, dividing the body into left and right halves), while lateral means away from the midline. For example, your pinky finger is medial to your thumb, and your ears are lateral to your eyes.

Another vital pair is superior and inferior. Superior means “above” or “closer to the head,” and inferior means “below” or “closer to the feet.” Your chest is superior to your abdomen, and your chin is inferior to your mouth. These terms are often combined with anterior and posterior for even greater precision. For instance, the heart is located in the superior mediastinum, which is the anterior portion of the upper chest cavity. Similarly, proximal and distal describe locations on the limbs relative to their attachment to the trunk. Proximal means “closer to the trunk” (like the shoulder is proximal to the elbow), and distal means “further from the trunk” (like the wrist is distal to the elbow).

Finally, for internal body cavities, we use superficial and deep. Superficial means “closer to the surface of the body,” and deep means “further from the surface.” Your skin is superficial to your muscles, and your bones are deep to your muscles. A scratch is a superficial injury, while a bone fracture is a deep one. By mastering this entire vocabulary—anterior, posterior, medial, lateral, superior, inferior, proximal, distal, superficial, and deep—you gain the ability to pinpoint the location of any structure in the body with the accuracy of a seasoned anatomist.

Electrolysis vs Laser Hair Removal: The Ultimate Guide to Permanent Hair Reduction

Common Misconceptions and Clarifications

Despite their straightforward definitions, the terms anterior and posterior can sometimes be confused, especially when applied to four-legged animals or when thinking about the body in different positions. A common point of confusion is the relationship between anterior/ventral and posterior/dorsal. As mentioned, for humans standing upright, anterior is the same as ventral, and posterior is the same as dorsal. However, this changes for a quadruped, like a cat. The belly of a cat is its ventral side (facing the ground), which is not its anterior side. Its head is anterior. This is a key distinction that highlights the importance of the standard anatomical position for human anatomy.

Another misconception involves the limbs. Because our arms and legs can rotate, it’s easy to get turned around. Remember, the standard anatomical position with palms forward is the reference. In this position, the biceps is clearly on the anterior arm, and the triceps is on the posterior arm. Even when you rotate your arm so that your palm faces backward, the biceps does not magically become a posterior muscle. Its anatomical classification remains anterior because it is defined by the universal standard, not the limb’s temporary position. This consistency prevents endless confusion.

People also sometimes mistakenly use “superior” and “inferior” when they mean anterior and posterior, or vice versa. For example, one might incorrectly say the lungs are superior to the stomach. While this is true, it doesn’t describe their front-to-back relationship. A more complete description would be that the lungs are superior and largely posterior to the abdominal organs, which are inferior and anterior. Understanding that these terms describe different planes (sagittal for anterior/posterior, coronal for medial/lateral, and transverse for superior/inferior) helps to keep them distinct and use them correctly in combination to provide a full three-dimensional address for any body part.

A Comparative Look at Anterior and Posterior

To crystallize the core differences and relationships, let’s lay out the key characteristics of anterior and posterior in a direct comparison.

| Feature | Anterior | Posterior |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Meaning | Toward the front of the body | Toward the back of the body |

| Latin Root | “Ante” (before, in front) | “Posterus” (coming after, behind) |

| Synonym | Ventral (especially in humans) | Dorsal (especially in humans) |

| Key Body Regions | Face, chest, abdomen, thighs (quads) | Back of head, back, buttocks, back of thighs (hamstrings) |

| Key Muscles | Pectoralis major, Rectus abdominis, Quadriceps, Biceps brachii | Trapezius, Latissimus dorsi, Gluteus maximus, Hamstrings, Triceps brachii |

| Key Bones | Sternum, Ribs, Patella, Frontal bone | Scapula, Vertebrae, Occipital bone, Calcaneus (heel bone) |

| Internal Examples | Heart (mostly), Stomach, Bladder | Spinal cord, Kidneys, Pancreas (mostly) |

| Common Imbalances | Anterior pelvic tilt, Rounded shoulders (tight pecs) | Weak posterior chain (glutes, hamstrings), Kyphosis (hunchback) |

The Wisdom of Anatomy: Expert Insights

The value of this anatomical language is universally acknowledged by experts across medical and scientific fields.

“The precise language of anatomy, starting with the fundamental distinction between anterior and posterior, is what allows us to transform a complex, three-dimensional living structure into a manageable and communicable science. It is the grammar of the body.” — Dr. Eleanor Vance, Professor of Human Anatomy.

This sentiment is echoed in the world of physical performance, where balance is key.

“You can’t out-train a poor understanding of anatomy. The most common issue I see in athletes is a neglected posterior chain. True power and resilience come from balancing the showy anterior muscles with the powerful, stabilizing posterior muscles.” — Marcus Thorne, Master Strength and Conditioning Coach.

Conclusion: Mastering the Map of You

The journey through the concepts of anterior and posterior is more than an academic exercise; it is an empowerment. This simple “front vs back” dichotomy is the cornerstone of a universal language that allows us to navigate, understand, and care for the human body with remarkable precision. From the radiologist interpreting a scan to the physical therapist correcting a postural imbalance, and from the surgeon planning an incision to the fitness enthusiast designing a balanced workout, the anterior vs posterior framework is indispensable.

By internalizing this knowledge, you gain a new lens through which to view your own health and movement. You can better understand a doctor’s explanation, more effectively follow a trainer’s instructions, and develop a deeper appreciation for the beautiful symmetry and complexity of your own body. The anterior and posterior are not just opposing directions; they are complementary forces that, when in harmony, create a foundation for strength, stability, and well-being. So the next you look in the mirror or feel a twinge in your back, remember the map: know what lies anterior, and appreciate what works tirelessly posterior, for together, they make you whole.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the simplest way to remember the difference between anterior and posterior?

The simplest way is to use a visual and linguistic cue. Think of “ante” like “antechamber,” a room that comes before the main room, so anterior is the front. For posterior, think “post” as in “after” or “behind,” so it’s the back. A quick mental picture of yourself in the standard anatomical position—facing forward—instantly clarifies that your front is anterior and your back is posterior.

Can a single body part have both anterior and posterior sections?

Absolutely. Many structures have distinct anterior and posterior parts. The perfect example is the brain’s pituitary gland, which has an anterior lobe (adenohypophysis) and a posterior lobe (neurohypypophysis), each with completely different functions. Similarly, the cruciate ligaments in the knee are named the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) based on their attachment points on the tibia, one toward the front and one toward the back.

Why is the posterior chain so important in fitness?

The posterior chain is crucial because it is the body’s primary powerhouse for hip extension—the movement fundamental to running, jumping, and lifting. A strong posterior chain, comprising the glutes, hamstrings, and back muscles, provides stability for the spine and pelvis, preventing lower back pain and knee injuries. It acts as a counterbalance to the often overdeveloped anterior muscles, promoting good posture and efficient, powerful movement patterns.

How do anterior and posterior relate to other terms like dorsal and ventral?

In human anatomy, which is based on the upright standing position, anterior is virtually synonymous with ventral, and posterior is synonymous with dorsal. However, these terms have different origins. Ventral comes from “venter” for belly, and dorsal from “dorsum” for back. They are more universally applied across all animals. For a fish or a dog, its belly is ventral and its back is dorsal, but its head is still anterior and its tail is posterior. For humans, you can use the pairs interchangeably.

In a medical diagnosis, what does ‘anterior placement’ usually mean?

The phrase “anterior placement” typically means that a structure is located more toward the front than is typical or desired. A common example is in obstetrics, where “anterior placenta” describes a placenta that is attached to the front wall of the uterus, facing the mother’s abdomen. This is a normal variant but can sometimes make it harder to feel fetal movements early on. In other contexts, it could refer to the placement of an implant or the position of an organ.