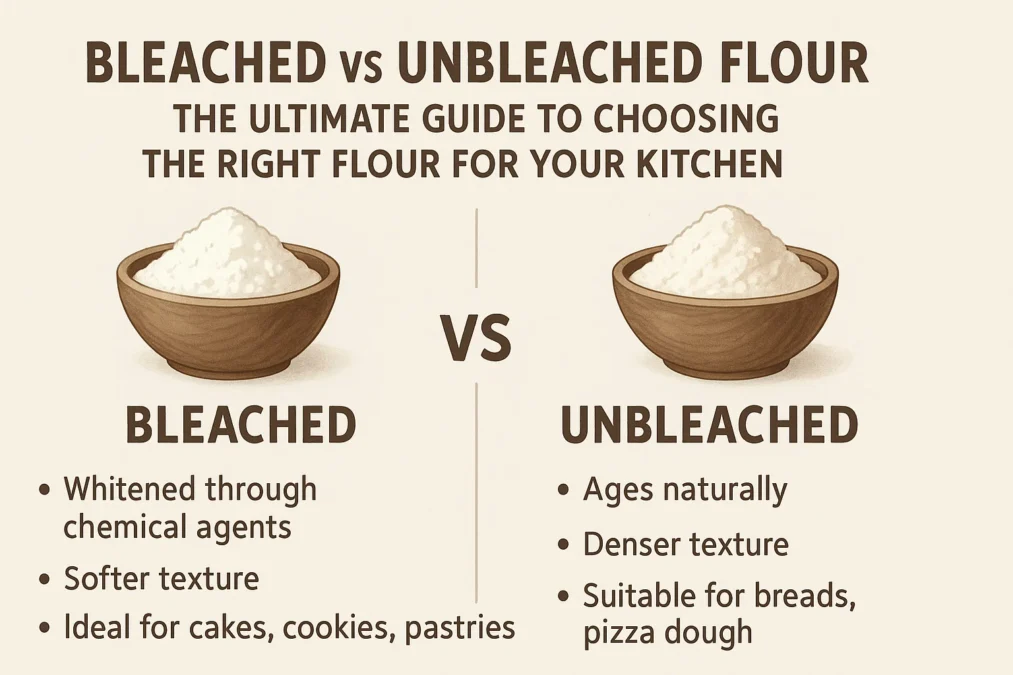

Walk down the baking aisle of any grocery store, and you’re faced with a wall of choices. Among the all-purpose flours, two main contenders vie for your attention: bleached and unbleached. They sit side-by-side, often at similar price points, leaving many home bakers wondering what exactly sets them apart. Is one healthier? Does one perform better? Is this just a marketing gimmick? The truth is, the choice between bleached and unbleached flour is one of the most common and consequential decisions a baker can make, impacting everything from the texture of your birthday cake to the height of your artisan bread loaf.

This isn’t just a debate about chemicals versus natural processes; it’s a conversation about science, tradition, and desired outcomes. The journey from a wheat berry to the fine powder in your bag involves several steps, and the path it takes determines its final character. Understanding the “why” behind the bleaching process, the properties it imparts, and the scenarios where unbleached flour truly shines will transform your baking from good to exceptional. This comprehensive guide will dive deep into the world of bleached vs unbleached flour, stripping away the confusion and giving you the confidence to choose the perfect flour for every recipe you create. We’ll explore the milling process, compare their performance in a variety of baked goods, tackle the health and safety questions head-on, and provide you with clear, actionable advice.

What is the Fundamental Difference Between Bleached and Unbleached Flour?

At its core, the difference between bleached and unbleached flour is a matter of time and treatment. Both start their lives identically: as wheat kernels that are milled into a fine powder. Freshly milled flour has a naturally pale yellow, almost creamy, hue. This color comes from pigments called carotenoids present in the wheat endosperm. If you were to bake with this flour immediately after milling, you’d notice its color and also its distinct, somewhat earthy flavor and a protein structure that isn’t yet at its peak for baking.

Unbleached flour is simply flour that has been allowed to age naturally. After milling, it is left to sit for a period of time, typically several weeks to a few months. During this natural aging process, oxygen in the air slowly works on the flour. It bleaches the carotenoid pigments, gradually turning the flour from pale yellow to the bright white we associate with all-purpose flour. Simultaneously, this oxidation strengthens the gluten-forming proteins, making the flour more elastic and better suited for creating strong doughs that can trap gas and rise well. Unbleached flour is essentially flour in its most straightforward, minimally processed form, with time as its primary agent of change.

Bleached flour, on the other hand, takes a shortcut. Instead of waiting for nature to take its course, millers use bleaching agents to rapidly achieve the same, or even a brighter, white color. These chemical agents, which are safe and approved by food regulatory bodies, work within hours to oxidize the flour. This process not only whitens the flour instantly but also alters the starch and protein structures in ways that are different from natural aging. The goal is to create a flour with specific functional properties that are highly desirable for certain types of baking, producing softer, more tender textures right out of the bag. The debate between bleached and unbleached flour, therefore, begins with this fundamental fork in the road: a slow, natural maturation versus a fast, controlled chemical treatment.

The Journey from Wheat to Flour: Understanding the Milling and Aging Process

To truly grasp the distinction, it helps to follow the flour’s journey. It all begins with the wheat berry, which is comprised of the bran (the fibrous outer shell), the germ (the nutrient-rich embryo), and the endosperm (the starchy core). For white all-purpose flour, the bran and germ are sifted out during milling, leaving mostly the endosperm. This endosperm is ground into a fine powder, and at this moment, it is technically “unbleached.” It possesses all the potential to become either product found on the supermarket shelf.

For unbleached flour, the path is straightforward. The freshly milled flour is aerated and stored in large bins. As it ages, the oxygen in the air consistently interacts with the flour’s components. The carotenoid pigments, which are sensitive to oxidation, break down, leading to the lightening of the flour’s color. This same oxidative process affects the glutenin and gliadin proteins that combine to form gluten. The oxygen helps to form stronger bonds between these protein chains, resulting in a more robust and elastic gluten network. This is why unbleached flour is often described as having a tougher or stronger gluten potential, which is a critical factor in yeast-raised breads that need structure to rise high.

The path for bleached flour is more accelerated and industrialized. To achieve the desired whiteness and baking properties without the wait, millers introduce bleaching and maturing agents. Common bleaching agents include benzoyl peroxide, which primarily targets the color pigments, and chlorine gas or chlorine dioxide, which both bleach the flour and chemically mature it. Chlorination, in particular, has a profound effect beyond just color. It lowers the pH of the flour, making it slightly more acidic, and it drastically alters the starch granules, making them more absorbent and able to swell and gelatinate at lower temperatures. This chemical process creates a flour that is inherently softer and better suited for producing tender cakes and pastries, but it also weakens the gluten structure, making it less ideal for chewy breads. The entire process is tightly controlled to ensure consistency and safety, producing a uniform product that performs predictably in specific baking applications.

A Head-to-Head Comparison: Bleached vs Unbleached Flour in the Kitchen

When you bring these two flours into your kitchen, their different histories manifest in clear, tangible differences that affect your baking. The choice between them is rarely about “good” versus “bad,” but rather about “right tool for the job.” Let’s break down their characteristics across several key categories.

In terms of color and appearance, unbleached flour has a slightly off-white, creamy, or ivory tone. It’s not starkly different, but side-by-side with its bleached counterpart, the difference is noticeable. Bleached flour is consistently brighter and pure white. This color difference can subtly influence the crumb color of your baked goods. A white cake made with bleached flour will have a brighter, snow-white interior, while one made with unbleached flour may have a slightly warmer, cream-colored crumb. For most applications, this is a minor aesthetic point, but for bakers seeking visual perfection in a pristine white angel food cake, it can be a deciding factor.

The texture and gluten strength between the two flours is where the most significant functional divergence occurs. Because of its natural aging process, unbleached flour typically develops a stronger, more elastic gluten network. This makes it the champion of bread baking. The strong gluten can stretch and trap the carbon dioxide gas produced by yeast, allowing bread loaves to achieve a better oven spring and a taller, airier structure with a satisfyingly chewy crumb. Bleached flour, having been treated with chemicals that weaken the gluten proteins, produces a much softer and more tender product. This is a distinct advantage when tenderness is the goal, such as in fluffy pancakes, delicate pie crusts, tender cookies, and soft layer cakes. The weakened gluten ensures these items don’t become tough or chewy.

Flavor and aroma also tell a story. Unbleached flour often retains a slightly more robust, wheaty, and nutty flavor compared to the very neutral taste of bleached flour. For many, this subtle complexity is a desirable trait, adding a layer of depth to whole wheat bread, pizza dough, and rustic pastries. Bleached flour, having undergone a more intensive process, has a very muted flavor profile. It is intentionally designed to be a blank canvas, allowing the other ingredients like butter, sugar, and vanilla to shine without any competing notes from the flour itself. This makes it ideal for recipes where a pure, unadulterated flavor is key.

Finally, the absorbency and performance of the two flours differ due to the chlorination process. The chemical treatment of bleached flour makes its starch granules more absorbent. This means that bleached flour can hold more liquid and fat in a recipe. This superior absorbency is why bleached flour is often recommended for high-ratio cakes (cakes with more sugar than flour) and can create exceptionally moist and tender baked goods. Unbleached flour has a lower absorption rate, which can sometimes lead to a slightly drier dough or batter if substituted directly without adjustment. Understanding this characteristic is crucial when adapting recipes or making substitutions.

Baking in Practice: Which Flour to Use for What

Knowing the theory is one thing; applying it to your favorite recipes is another. Let’s translate these characteristics into practical baking advice to take the guesswork out of your next project.

For breads and pizza doughs, unbleached flour is almost always the superior choice. The strong, elastic gluten network it develops is essential for creating the structure that allows yeast-leavened doughs to rise to their full potential. Whether you’re crafting a crusty baguette, a soft sandwich loaf, or a chewy, Neapolitan-style pizza crust, the protein in unbleached all-purpose or bread flour provides the necessary backbone. The gluten can stretch into thin, strong membranes that form the gas-trapping cells within the dough, leading to an open, airy crumb and a fantastic oven spring. Using bleached flour for bread can result in a denser, more cake-like loaf that doesn’t achieve the same height or chewy texture, as the weakened gluten strands are more prone to tearing under the pressure of the gas.

When it comes to pastries, cakes, and cookies, the tables often turn. For tender, flaky pie crusts, the goal is to minimize gluten development. This is where bleached flour frequently has the edge. The chemically weakened gluten proteins in bleached flour are less likely to form a tough network when worked with fat and liquid, leading to a crust that is tender and melts in your mouth. Similarly, for delicate cakes like vanilla layer cake, pound cake, and especially angel food or chiffon cakes, the soft, high-absorbency nature of bleached flour creates a fine, soft crumb and a lofty texture. The same principle applies to cookies where a soft, cake-like texture is desired. The neutral flavor of bleached flour also ensures that the butter and vanilla notes are the stars of the show.

However, the world of baking is full of nuance. For certain cookies, like a sturdy, chewy chocolate chip cookie, some bakers prefer the slight structural support and flavor complexity of unbleached flour. For biscuits and scones, it can be a toss-up; bleached flour may yield a more tender result, while unbleached can provide a bit more structure and a pleasing, wheaty flavor. The key is to understand the textural goal of your recipe. If the description includes words like “tender,” “soft,” “delicate,” or “light,” bleached flour is likely the intended choice. If it calls for “chewy,” “rustic,” “crusty,” or “airy,” unbleached flour is probably your best bet.

Baking Soda vs Baking Powder: The Ultimate Guide to Unlocking Baking Success

The Health, Safety, and Nutritional Debate

This is the area that causes the most anxiety for home bakers. The word “chemical” can be alarming, and many people naturally gravitate towards “unbleached” assuming it is the healthier option. It’s important to separate fact from fear and look at the science.

From a nutritional standpoint, the differences between bleached and unbleached flour are minimal. The bleaching process does not significantly alter the core macronutrients of the flour. Both types provide similar amounts of calories, carbohydrates, protein, and fiber. Some critics have pointed out that the bleaching process can destroy small amounts of certain nutrients, notably vitamin E and some unsaturated fatty acids. However, it’s crucial to remember that in many countries, including the United States, all white flour (both bleached and unbleached) is required by law to be enriched. This means that after milling, specific B vitamins (thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, folic acid) and iron are added back to the flour to restore the nutrient levels lost when the bran and germ are removed. Therefore, the enrichment process has a far greater impact on the final nutritional profile than the bleaching process does.

The safety of the bleaching agents themselves is a topic regulated by strict government bodies. In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies the substances used, such as benzoyl peroxide and chlorine gas, as “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS) when used in accordance with good manufacturing practices. The amounts used in flour treatment are precisely controlled to be safe for human consumption. The chemical reactions that occur during the bleaching and maturing process are designed to leave little to no residue in the final product. For the vast majority of the population, consuming bleached flour poses no known health risk.

Despite the official safety endorsements, some consumers and health advocates remain cautious. They prefer to follow a precautionary principle, opting for foods with fewer synthetic processing aids. For these individuals, choosing unbleached flour is a way to minimize their exposure to any chemical additives, regardless of their official safety status. This is a personal choice based on individual comfort levels and philosophies about food. There is also a segment of the population that reports being able to taste a slight chemical aftertaste in bleached flour, though this is not a universal experience. Ultimately, while the scientific consensus affirms the safety of bleached flour, the decision to use unbleached flour as a more “whole” or “natural” product is a valid personal preference.

Common Myths and Misconceptions About Flour

The world of baking is ripe with folklore, and the topic of bleached versus unbleached flour is no exception. Let’s debunk a few of the most persistent myths to clear the air.

One of the most common myths is that you can always substitute bleached and unbleached flour one-for-one in any recipe without consequence. While you can often get away with it, especially in forgiving recipes like some cookies, it is not a universally true statement. As we’ve explored, their different protein structures, absorbency rates, and pH levels can lead to noticeably different results. Substituting unbleached flour in a cake recipe designed for bleached flour might yield a tougher, denser cake because the stronger gluten develops more readily. Conversely, using bleached flour in a bread recipe can lead to a loaf that doesn’t rise as well and has a gummier crumb. For best results, it’s wise to use the type of flour specified in the recipe, particularly for precision-sensitive baked goods.

Another widespread belief is that unbleached flour is inherently healthier or more natural than bleached flour. While “unbleached” does mean it hasn’t been treated with chemical bleaching agents, it’s important to remember that both are highly processed products. The wheat bran and germ, which contain the majority of the fiber, vitamins, and minerals, have been removed from both to create a shelf-stable, white powder. The term “natural” is somewhat misleading when applied to any refined white flour. The most significant health choice in flour is moving from white flour (whether bleached or unbleached) to whole wheat flour, which retains the entire nutrient-rich kernel.

A third misconception is that bleached flour is a modern, inferior product created solely for corporate profit. While it’s true that the industrialization of food production led to the development of chemical bleaching to speed up production and ensure consistency, the desire for white flour is ancient. For centuries, bakers and millers have sought ways to produce whiter flour, as it was historically associated with purity, refinement, and higher social status. Methods like using alum date back to the Roman era. Modern bleaching is simply a more efficient and controlled method of achieving a desired aesthetic and functional characteristic that bakers have valued for a very long time. It was developed to meet market demands for consistent, white, and soft flour, not just to cut costs.

How to Choose the Right Flour for Your Pantry

So, with all this information, how should you stock your kitchen? The answer depends entirely on your baking habits and personal philosophy.

For the avid bread baker, your pantry should be dominated by unbleached flour. Keeping a large bag of unbleached all-purpose flour on hand is a great start, and if you bake bread frequently, investing in a high-protein unbleached bread flour is a game-changer for achieving professional-level results. The strong gluten network is non-negotiable for good bread structure. You might also want to explore other unbleached specialty flours, like whole wheat or rye, to incorporate into your doughs for added flavor and nutrition.

For the dedicated pastry chef or cake enthusiast, bleached flour is your workhorse. Its ability to produce tender, soft textures with a neutral flavor makes it ideal for cakes, cupcakes, muffins, tender pie crusts, and biscuits. If your primary baking projects are birthday cakes, Christmas cookies, and weekend pancakes, you will be happier with the results from a bag of bleached all-purpose flour. Its higher absorbency also helps create moister cakes that stay fresh longer.

For the all-around home baker who does a bit of everything, the most practical solution is to keep both types of flour on hand. Have a container of unbleached all-purpose flour for your bread, pizza, and pasta doughs, and a container of bleached all-purpose flour for your cakes, pastries, and quick breads. This two-flour system ensures you always have the right tool for the job and allows you to follow recipes precisely without compromise. Label them clearly to avoid mix-ups. This approach acknowledges that both bleached and unbleached flour have valuable, distinct roles to play in a well-rounded baking repertoire.

The Final Verdict: It’s All About the Crumb

The journey through the world of bleached and unbleached flour reveals that this is not a simple binary of right and wrong. It is a fascinating case study in how subtle processing differences can dramatically alter an ingredient’s performance. Bleached flour, with its weak gluten, high absorbency, and neutral taste, is the undisputed champion of tender, delicate baked goods. Unbleached flour, with its strong gluten and nuanced flavor, is the foundation upon which great bread is built.

The choice between them is a powerful tool in the hands of an informed baker. It allows you to exert control over the very texture and structure of your creations. By understanding the science behind the bag, you move from blindly following recipes to actively engineering your outcomes. You learn that the path to a flaky pie crust is paved with bleached flour, while the road to a chewy baguette is built with unbleached. So, the next time you stand in the baking aisle, you can make your choice not out of confusion or assumption, but with the confidence of a baker who knows exactly what kind of magic they want to create in the oven.

Frequently Asked Questions About Bleached and Unbleached Flour

What is the main difference between bleached and unbleached flour?

The main difference lies in the post-milling processing. Unbleached flour is naturally aged and whitened over time by exposure to oxygen. Bleached flour is treated with FDA-approved chemical agents to rapidly whiten it and alter its protein and starch properties. This fundamental processing difference results in unbleached flour having a stronger gluten network and a slightly off-white color, while bleached flour has a weaker gluten network, a pure white color, and higher absorbency.

Can I use bleached flour instead of unbleached flour for bread?

You can, but the results will not be optimal. Bleached flour has a weaker gluten structure due to the chemical treatment it undergoes. Since bread baking relies on strong, elastic gluten to trap gas and rise, using bleached flour will likely result in a denser loaf with less oven spring and a more cake-like, rather than chewy, crumb. For the best bread, unbleached all-purpose or bread flour is highly recommended.

Does unbleached flour taste different than bleached flour?

Yes, there is a subtle but noticeable difference in taste for many people. Unbleached flour often has a slightly more robust, wheaty, and nutty flavor. Bleached flour, having been processed to be more neutral, has a very mild, almost blank flavor profile. This makes bleached flour ideal for recipes where you don’t want the flour’s taste to compete with other ingredients, like in a delicate vanilla cake.

Is unbleached flour healthier for you than bleached flour?

From a strict nutritional standpoint, the difference is negligible. Both are refined flours that have been stripped of the bran and germ, and both are enriched with the same B vitamins and iron. The bleaching process does destroy trace amounts of vitamin E, but this is not a significant source of the nutrient in our diets. The choice is more about personal preference regarding food processing. Some people prefer to avoid the chemical agents used in bleaching, which is a valid personal decision, but it does not equate to a major health advantage.

Why do some recipes specifically call for bleached or unbleached flour?

Recipes are developed with the specific functional properties of a flour in mind. A recipe for a tender, fluffy layer cake will often call for bleached flour because its weak gluten and high absorbency are crucial for achieving that soft, fine texture. A recipe for a crusty artisan bread will call for unbleached flour because its strong gluten is essential for creating an open, airy crumb. Using the specified flour ensures you get the result the recipe developer intended.

Comparison Table: Bleached vs Unbleached Flour at a Glance

| Feature | Bleached Flour | Unbleached Flour |

|---|---|---|

| Processing | Chemically treated with agents like benzoyl peroxide or chlorine gas to whiten and mature quickly. | Naturally aged and whitened over several weeks through exposure to oxygen. |

| Color | Bright, pure white. | Off-white, creamy, or ivory. |

| Gluten Strength | Weaker gluten network due to chemical oxidation. | Stronger, more elastic gluten network due to natural oxidation. |

| Texture Best For | Tender, soft baked goods (cakes, cookies, pie crusts, biscuits). | Chewy, structured baked goods (bread, pizza dough, bagels). |

| Flavor | Very neutral, a blank canvas. | Slightly nutty, wheaty, more robust. |

| Absorbency | Higher; starch granules are altered to absorb more liquid and fat. | Lower; less able to hydrate than bleached flour. |

| Common Uses | Layer cakes, pancakes, muffins, pastries. | Artisan bread, sourdough, pasta, pizza crust. |

Expert Quotes on Flour

“A baker chooses their flour like a painter chooses their brush. Understanding the difference between bleached and unbleached flour is fundamental to controlling texture. I reach for bleached for a featherlight cake and unbleached for a bread with crackling crust and an open crumb.” — Sarah Johnson, Master Baker and Author of “The Flour Code”

“The debate often gets oversimplified. It’s not about ‘chemicals are bad.’ It’s about functionality. The chlorination of bleached flour uniquely modifies the starch, making it indispensable for the structure of a high-ratio cake. It’s a specific tool for a specific job.” — Dr. Michael Lee, Food Scientist

“In my kitchen, unbleached flour is the default. I appreciate the subtle, wheaty complexity it adds to even a simple sugar cookie, and its reliable protein strength gives me the confidence that my sourdough will always have a strong backbone to rise.” – Maria Garcia, Artisan Baker and Instructor

Conclusion

The journey through the nuanced world of bleached versus unbleached flour ultimately leads to a place of empowerment for the home baker. This is not a choice dictated by a simple rule of thumb, but rather a strategic decision based on desired outcome. Bleached flour, the product of efficient modern processing, is your secret weapon for achieving unparalleled tenderness and a pristine, neutral canvas in pastries and cakes. Unbleached flour, a testament to traditional, slow aging, is the foundational ingredient for building the robust, chewy, and flavorful structures of great bread and pizza.

Armed with the knowledge of how processing affects color, gluten strength, absorbency, and flavor, you can now move beyond recipe dogma. You understand that a direct substitution is not always a one-to-one swap and that each flour has a distinct personality shaped by its journey from mill to bag. Whether you stock both for specialized tasks or choose one as your everyday hero based on your baking passions, your choice is now an informed one. So, embrace the flour that aligns with your culinary vision. Let the pursuit of a flaky crust guide you to bleached, and the dream of a chewy, hole-riddled crumb draw you to unbleached. Happy baking