Stepping into the world of firearms, whether for sport, hunting, or personal defense, means encountering a fundamental choice that defines your entire experience: centerfire vs rimfire ammunition. This isn’t just a minor technical detail; it’s the core of how your firearm operates, its capabilities, and its limitations. You might have heard the terms tossed around at the range or seen them on ammo boxes, but understanding the real-world implications of this choice is crucial for any shooter. This deep dive will demystify these two priming systems, going far beyond the basics to explore the history, mechanics, and practical applications that make each type unique. By the end, you’ll not only know the difference but you’ll be equipped to make the perfect choice for your specific needs, ensuring your time spent shooting is safe, effective, and enjoyable.

The divide between centerfire and rimfire is one of the oldest in modern shooting sports. Rimfire came first, a revolutionary invention that made cartridges as we know them possible. Centerfire followed, offering a more powerful and reliable system that would come to dominate most shooting disciplines. Today, both coexist, each having carved out its own vital niche. The choice between them isn’t about which one is objectively “better,” but rather which one is “better for you” in a given situation. Are you plinking cans on a weekend, hunting big game, or preparing for a home defense scenario? The answer to that question will point you directly to the right cartridge type. This comprehensive guide will serve as your roadmap, providing the expert knowledge you need to navigate the landscape of centerfire vs rimfire with confidence.

The Heart of the Matter: How They Actually Work

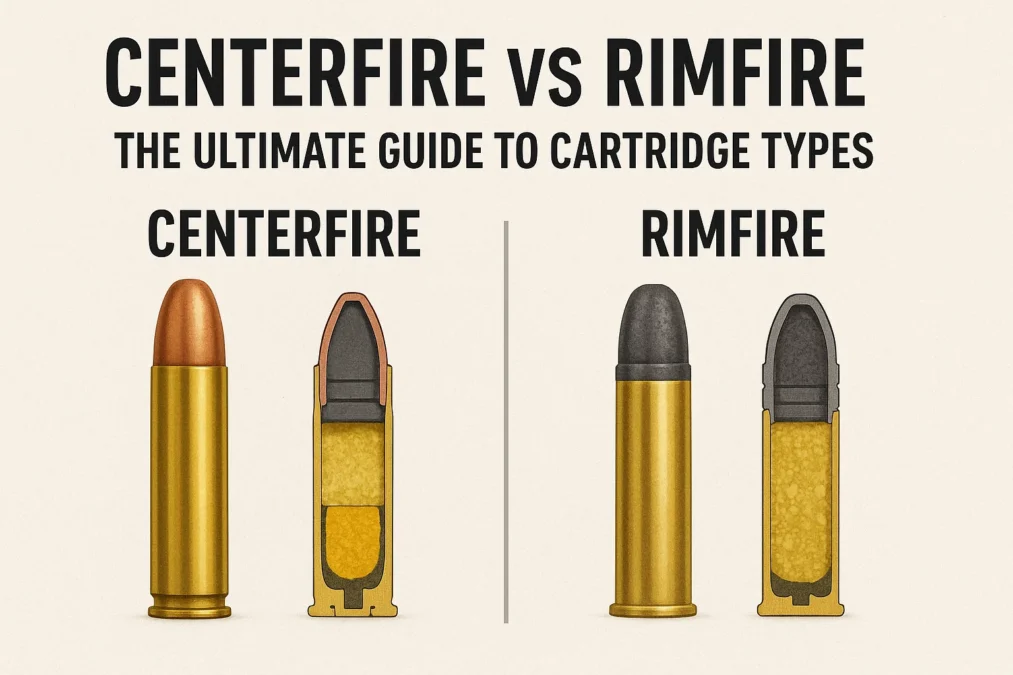

To truly grasp the centerfire vs rimfire debate, you need to understand what happens inside the cartridge the moment the firing pin strikes. The fundamental difference lies in the location of the impact-sensitive priming compound and how it’s ignited to set off the main powder charge. This single engineering decision creates a cascade of differences in performance, reliability, and application.

A rimfire cartridge is a beautifully simple design. The cartridge case itself, typically made of a softer brass, has a hollow rim running around its base. This rim is filled with a small amount of shock-sensitive priming compound. When you pull the trigger, the firing pin strikes anywhere on this flanged rim, crushing it and instantly igniting the primer. This flash travels through a small flash hole (in some designs) or directly into the main case, lighting the gunpowder and generating the gas that propels the bullet down the barrel. This simplicity is rimfire’s greatest strength and its primary weakness. Because the priming compound is spun into the rim during manufacturing, the case walls must be thin enough to be reliably crushed by the firing pin. This limits the pressure the case can withstand, which in turn limits the power and velocity of the cartridge.

In contrast, a centerfire cartridge takes a more robust and complex approach. Instead of the primer being housed in the rim, it is contained in a separate, self-contained primer cup that is press-fit into a dedicated pocket in the center of the cartridge case head. This primer cup is a small metal capsule containing its own anvil and a pellet of priming compound. When the firing pin strikes the center of this primer cup, it crushes the compound against the internal anvil, creating a hot jet of flame. This jet is channeled through a flash hole in the case head and into the main powder charge, causing ignition. This design allows for a much stronger, thicker case head that can contain significantly higher internal pressures. Furthermore, the primer itself is a separate, reusable component (in the context of reloading), making the entire system more versatile and powerful.

A Journey Through History: The Evolution of Two Systems

The story of centerfire vs rimfire is a tale of innovation and adaptation. Rimfire ammunition holds the distinction of being the first truly integrated metallic cartridge to achieve widespread commercial success. Its invention in the mid-19th century, notably with the .22 Short cartridge in 1857, was a monumental leap forward from the messy and complicated process of loading muzzleloaders with loose powder, ball, and primer. For the first time, a shooter had a self-contained unit that was relatively weatherproof and could be loaded quickly. This technology quickly became the standard for small-caliber firearms and saw use in everything from pocket revolvers to early military rifles.

However, the limitations of rimfire technology soon became apparent. The low-pressure design meant it was unsuitable for large, powerful cartridges needed for big game hunting and military applications. The quest for more power and reliability led to the development of the centerfire system. While several inventors worked on the concept, the centerfire cartridge as we know it was largely perfected and popularized in the latter half of the 1800s. Cartridges like the .45-70 Government and the .303 British adopted the centerfire design, allowing militaries to field powerful, reliable repeating rifles. The strength of the centerfire case also made it reloadable, a huge advantage for both frugal sportsmen and military logistics. Over time, centerfire became the undisputed king for nearly every application except for one area where rimfire’s low cost and low recoil remained king: the .22 Long Rifle.

The King of Plinking: The .22 Long Rifle and Rimfire’s Domain

When people think of rimfire, one cartridge immediately comes to mind: the legendary .22 Long Rifle, or .22 LR. It is the quintessential example of rimfire ammunition and arguably the most popular cartridge in the world. Its enduring success perfectly illustrates the ideal use case for rimfire technology. The .22 LR is inexpensive to produce, has virtually no recoil, and produces very little noise compared to centerfire rounds. This makes it the perfect tool for a multitude of tasks where high power is not just unnecessary, but undesirable.

The primary domain of rimfire, led by the .22 LR, is training and pure fun, often called “plinking.” Introducing a new shooter, especially a child, to the sport is best done with a .22 rifle. The lack of loud bang and punishing recoil prevents the development of a flinch and allows the novice to focus on the fundamentals of marksmanship: sight alignment, breath control, and trigger squeeze. For experienced shooters, a .22 is an invaluable tool for maintaining skills without the high cost and fatigue associated with high-volume centerfire practice. Furthermore, rimfire is exceptionally effective for pest control at short ranges. Dealing with squirrels, rats, or other small varmints around a property is a job perfectly suited for a .22, as it has more than enough power for the task without the overpenetration and noise of a larger round. While there are other rimfire calibers like the .17 HMR and .22 WMR that offer more power and range, they all operate within the same pressure constraints of the rimfire design, keeping them in the realm of small game and varmints.

“The .22 Long Rifle is the gateway drug to the shooting sports. It’s affordable, fun, and teaches the fundamentals without any of the intimidation.” – An experienced firearms instructor.

Power and Versatility: The World of Centerfire Ammunition

If rimfire is the domain of practice and small game, centerfire is the realm of serious application. The robust design of a centerfire cartridge allows it to generate immense pressures, which translates to higher bullet velocities, flatter trajectories, and vastly more energy downrange. This raw power, combined with the ability to handle a massive variety of bullet weights and types, makes centerfire ammunition the undisputed choice for nearly every demanding task a shooter might face.

When the discussion turns to hunting, centerfire is the only option for game larger than small varmints. From deer and antelope cartridges like the .243 Winchester and .30-30 Winchester, to medium and large game rounds like the .308 Winchester and .30-06 Springfield, all the way up to the massive magnum cartridges designed for elk, moose, and dangerous African game, they are all centerfire. The power to ensure a quick, ethical kill on larger animals simply cannot be achieved within the pressure limits of a rimfire case. Furthermore, centerfire is the universal standard for self-defense and military use. Whether it’s a 9mm pistol on a police officer’s hip, a 5.56mm NATO rifle in the hands of a soldier, or a 12-gauge shotgun slug for home defense, these are all centerfire cartridges. Their superior reliability, stopping power, and ability to function in semi-automatic actions make them indispensable for life-or-death situations. The world of long-range precision shooting is also exclusively dominated by centerfire cartridges, which can propel heavy, aerodynamically efficient bullets accurately over distances of a thousand yards or more.

Cost Considerations: Upfront and Long-Term Investment

The topic of cost is a major factor in the centerfire vs rimfire decision, but it’s more nuanced than a simple price-per-round comparison. On the surface, the winner is clear: rimfire is dramatically cheaper. A box of 50 rounds of standard .22 Long Rifle ammunition can often be found for just a few dollars, while a box of 20 rounds of common centerfire rifle ammo like .223 Remington will typically cost $10 to $15, and larger hunting rounds can be $30 or more per box. This makes rimfire the undisputed champion for high-volume shooting on a budget.

However, this only tells part of the story. The initial purchase price of the firearms themselves must be considered. While there are very expensive target-grade .22 rifles, the general rule is that a quality rimfire rifle or pistol will be less expensive than its centerfire counterpart. But the long-term economic picture changes when you introduce the concept of reloading. Centerfire cartridges are reloadable. The brass case, which is often the most expensive component of a new cartridge, can be reused multiple times. A dedicated reloader can often handload their own centerfire ammunition for significantly less than the cost of factory new ammo, and they can also tailor the load to their specific firearm for ultimate accuracy. Rimfire cartridges, with their priming compound spun into the rim, are impossible to reload safely or practically. They are truly a “fire and forget” proposition. Therefore, for a shooter who plans to send thousands of rounds downrange, the high upfront cost of a centerfire firearm and reloading equipment can be amortized over time, potentially making it more economical than buying endless boxes of factory rimfire ammo—though the time investment is a factor.

Reliability and Misfires: A Question of Consistency

In the world of ammunition, reliability is paramount. Whether you’re in a competition, hunting season, or a defensive scenario, you need absolute confidence that your cartridge will fire when the trigger is pulled. This is an area where the centerfire design holds a significant and well-deserved advantage. The separate, sturdier primer cup in a centerfire cartridge is consistently struck with direct, focused force by the firing pin. The priming compound is also generally more stable and less susceptible to environmental degradation over time.

Rimfire ammunition, by its nature, is more prone to misfires or “duds.” The priming compound is distributed unevenly within the hollow rim during the manufacturing process. While quality control is generally very good from major manufacturers, it’s not uncommon to experience the occasional round that fails to fire. When this happens, the firing pin may have struck a spot in the rim that simply didn’t have enough priming compound. This is why it’s always recommended to immediately re-chamber and try to fire a rimfire dud a second time—rotating the cartridge might present a fresh section of the rim with primer to the firing pin. For plinking, this is a minor annoyance. For a critical application like self-defense or hunting, an unreliable round is completely unacceptable. This inherent variability is the primary reason why no serious defensive firearm is chambered in rimfire.

The Reloading Revolution: Why Centerfire Takes the Crown

For a large segment of the shooting community, the hobby doesn’t end at pulling the trigger; it extends to the reloading bench. Handloading is the process of assembling your own ammunition from components: once-fired brass, new primers, powder, and bullets. It’s a pursuit driven by passion, precision, and economics, and it is an arena where centerfire is the only player. The very design of a centerfire cartridge is built for this. The spent primer can be decapped, the brass case can be cleaned, resized, and prepped, and a new primer can be seated into the pocket.

Rimfire cartridges are fundamentally incompatible with reloading. The act of firing crushes the rim, deforming it permanently. There is no way to safely or effectively replace the priming compound that is integral to the case itself. This makes rimfire a purely consumable product. For reloaders, the centerfire system offers immense benefits. It allows shooters to create custom ammunition tuned for their specific firearm, often achieving accuracy levels that surpass factory ammunition. It also provides a solution during periods of ammunition scarcity, as components can sometimes be found when pre-made boxes cannot. The ability to recycle brass cases also appeals to the frugal and environmentally conscious shooter. This entire dimension of the shooting sports is a closed door to those who only shoot rimfire, solidifying centerfire’s role as the more versatile and technically engaging system.

Mace vs Pepper Spray Which is Better for Self-Defense?

Choosing Your Tool: Matching the Ammo to the Mission

The entire centerfire vs rimfire debate ultimately boils down to a simple principle: choosing the right tool for the job. There is no winner-take-all answer. Instead, a smart shooter builds an arsenal, or at least a knowledge base, that allows them to select the perfect ammunition for their intended activity. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each system is the key to making safe, effective, and economical choices.

For missions requiring minimal noise, low recoil, and extreme cost-effectiveness, rimfire is the undisputed champion. This includes introducing new shooters to the sport, casual plinking at the range, small game hunting (squirrels, rabbits), and pest control at short distances (under 100 yards). A .22 LR rifle is arguably the most fun you can have with a firearm for the least amount of money, and it serves as a foundational training tool for all shooters. For any mission that demands power, long-range accuracy, absolute reliability, or ethical takedown of medium to large game, centerfire is the only choice. This includes deer hunting, home defense, competitive shooting (except for specific .22 competitions), long-range precision shooting, and military or law enforcement applications. The power and versatility of centerfire cartridges make them the workhorses of the serious shooting world.

| Feature | Rimfire Ammunition | Centerfire Ammunition |

|---|---|---|

| Priming System | Primer compound spun inside the cartridge’s rim. | Separate primer cup seated in center of case head. |

| Typical Calibers | .22 LR, .22 WMR, .17 HMR | 9mm, .223 Rem, .308 Win, .30-06, countless others |

| Relative Cost | Very Low (cost per round) | Moderate to Very High (cost per round) |

| Power & Pressure | Low pressure, low power, short range | High pressure, high power, long range |

| Recoil & Report | Very low recoil, quieter report | Moderate to very high recoil, louder report |

| Reloadable? | No | Yes |

| Primary Uses | Training, plinking, small game/pest control | Hunting, self-defense, competition, military/law enforcement |

| Reliability | Good, but higher chance of duds/misfires | Excellent, very reliable ignition |

The Future of both Cartridge Types

The evolution of ammunition is a slow process, but both centerfire and rimfire continue to adapt and thrive. Rimfire technology has seen innovations in recent decades, most notably with the introduction of high-performance cartridges like the .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire (.17 HMR). This cartridge pushes the boundaries of rimfire performance, offering much higher velocity and flatter trajectory than a .22 WMR, making it excellent for longer-range varmint control. Manufacturers are also constantly improving the consistency and reliability of rimfire priming compounds.

The future of centerfire is focused on efficiency, advanced materials, and specialized projectile design. The trend in many shooting disciplines is towards cartridges that offer superior ballistic performance with less recoil and powder consumption. The proliferation of 6mm and 6.5mm cartridges for long-range precision shooting is a testament to this. Furthermore, advancements in bullet technology—such as polymer-tipped, expanding designs for hunting and specialized frangible projectiles for training—are all built upon the robust and versatile centerfire platform. While entirely new priming systems may be on the distant horizon, the fundamental centerfire vs rimfire dichotomy is so well-established and serves its respective purposes so effectively that both will remain essential pillars of the shooting world for generations to come.

Conclusion

The journey through the intricacies of centerfire vs rimfire ammunition reveals a landscape not of competition, but of complement. One is not inherently superior to the other; they are different tools designed for different tasks. Rimfire, with its humble .22 LR cartridge, is the accessible, economical, and low-recoil gateway to the shooting sports. It is the perfect tool for learning fundamentals, plinking for fun, and handling small pests. Centerfire, in its vast array of forms, is the system of power, precision, and responsibility. It is the choice for hunters, defenders, competitors, and professionals who require reliable, potent performance.

The most knowledgeable shooters aren’t those who pledge allegiance to one type alone, but those who understand and appreciate the role of both. They own a .22 rifle for inexpensive practice and teaching newcomers, and they own centerfire firearms for their primary hunting or defensive needs. The centerfire vs rimfire discussion is ultimately about making informed choices. By understanding the mechanics, history, cost, and applications of each system, you can confidently select the right ammunition for your purpose, ensuring safety, success, and satisfaction every time you step up to the firing line.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a rimfire gun fire a centerfire cartridge, or vice versa?

Absolutely not. The firearms are designed and built specifically for one type of cartridge or the other. A centerfire cartridge will not fit in a rimfire chamber, and attempting to fire a rimfire cartridge in a centerfire gun is extremely dangerous and could cause a catastrophic failure. The chambers are machined to very specific dimensions to headspace (position) the cartridge correctly for the firing pin to strike the right spot. Always use only the ammunition specifically marked for your firearm.

Is .22 LR considered good for self-defense?

While a .22 LR can certainly be lethal, it is universally considered a poor choice for self-defense when compared to any modern centerfire option. The reasons stem from the rimfire vs centerfire design differences: rimfire ammunition has a significantly higher rate of misfires, lacks the reliable stopping power (energy transfer) needed to quickly neutralize a threat, and its small bullets are less effective at penetrating to vital organs through heavy clothing or if striking at an oblique angle. For defending your life, a centerfire pistol caliber like 9mm, .40 S&W, or .45 ACP is the recommended minimum.

Why is rimfire ammunition so much cheaper than centerfire?

The cost difference in the centerfire vs rimfire debate comes down to materials, manufacturing complexity, and economies of scale. Rimfire cartridges use less brass (thinner case walls), less lead (lighter bullets), and far less gunpowder. The manufacturing process, while precise, is highly automated for billions of rounds of .22 LR, driving the cost per unit extremely low. Centerfire cartridges use more and higher-quality materials, including a separate brass primer cup, and are often loaded with more expensive powders and advanced bullet designs. The higher pressure requirements also demand more rigorous quality control.

What does “magnum” mean in rimfire, like .22 WMR?

In the context of rimfire, “magnum” denotes a more powerful cartridge within the constraints of the rimfire design. The .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (.22 WMR) uses a longer and slightly larger diameter case than a .22 LR, allowing for a larger powder charge. This results in higher velocity and energy, extending the effective range for varmint hunting. However, it’s crucial to remember that even a “magnum” rimfire round operates at pressures far below those of any centerfire cartridge. It expands the capabilities of rimfire but does not bridge the gap to centerfire power.

Are there any centerfire cartridges that are as low-recoil as a .22 LR?

There are centerfire cartridges with very mild recoil, such as the .17 Hornet or .22 Hornet, but they still generate significantly more recoil, noise, and blast than a standard .22 Long Rifle. The fundamental physics of burning more powder behind a similar or slightly larger bullet creates more energy, which translates to more recoil. The .22 LR is in a class of its own for minimal recoil and report, which is a primary reason for its enduring popularity for training and casual shooting.