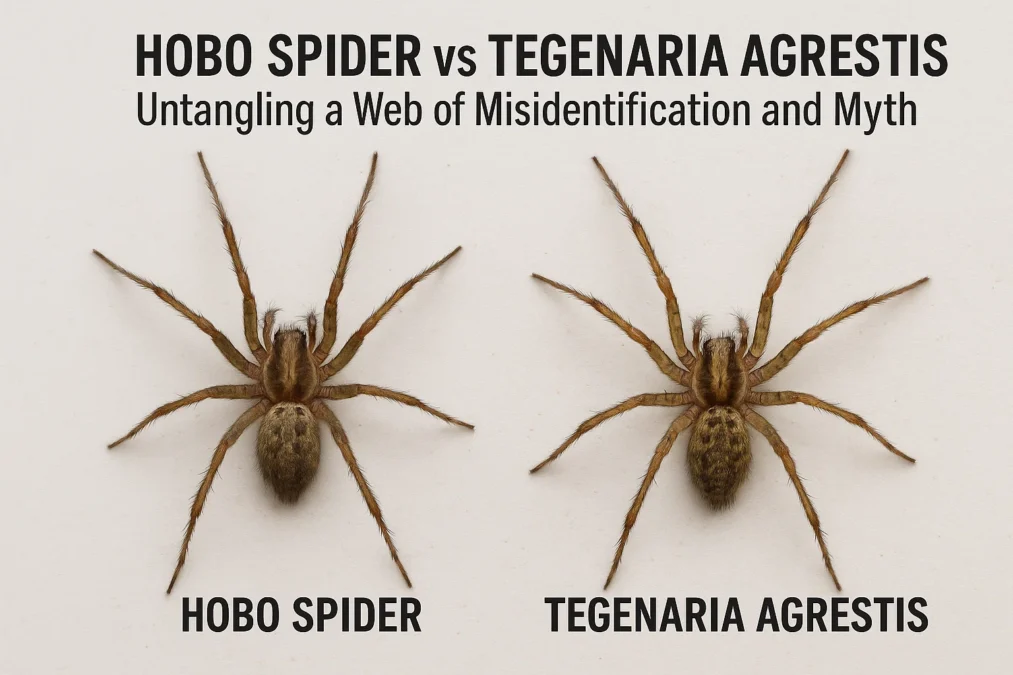

For decades, a shadow of fear has been cast over a particular eight-legged resident of the Pacific Northwest and beyond: the hobo spider. Synonymous with necrotic wounds and aggressive behavior, its name alone evokes a sense of dread. But what if much of what we think we know about this arachnid is based on a case of profound misidentification and decades of entrenched myth? The story of the hobo spider is inextricably linked to its scientific name, Tegenaria agrestis, and understanding the difference between the common name and the actual creature is the first step in demystifying this much-maligned animal. This article dives deep into the tangled web of the hobo spider vs Tegenaria agrestis, separating sensationalized fiction from scientific fact, and providing you with a clear, expert-guided understanding of the spider that may be sharing your home.

The confusion starts with the names themselves. To the average person, “hobo spider” and “Tegenaria agrestis” are used interchangeably, referring to the same brown, funnel-weaving spider. For many years, even scientific and medical literature used them as synonyms. However, a crucial clarification has emerged: while “hobo spider” is the common name given to a specific species in North America, Tegenaria agrestis is its formal Latin binomial. They are one and the same organism. The real conflict isn’t between two different names, but between the terrifying reputation of the “hobo spider” and the far more benign reality of the actual spider, Tegenaria agrestis. Our journey will explore the origins of its nasty reputation, the science that has largely exonerated it, and how to truly identify it among a crowd of similar-looking house spiders.

The Identity Crisis: Unpacking the Names and Origins

The tale of the hobo spider begins not in America, but in Europe. Tegenaria agrestis is a native species to Western Europe, where it commonly lives in fields and on the edges of human habitation. The name agrestis even derives from Latin for “of the fields” or “rural,” hinting at its preferred habitat. For centuries, it coexisted with humans in Europe without note or notoriety. It was just another harmless, common spider. The story took a dramatic turn when the species was accidentally introduced to the Pacific Northwest of the United States, likely in the early 20th century through shipping ports like Seattle. Finding a favorable climate with no natural predators, its population expanded rapidly.

In its new North American home, this foreign spider needed a new common name. It acquired the moniker “hobo spider” in the 1960s. The origin of the name is somewhat debated. One popular theory suggests it was dubbed the “hobo” because its tendency to wander into homes coincided with the migration patterns of itinerant workers during the Great Depression. Another theory points to the erratic, “hopping” pattern it sometimes makes when provoked, which could have been misinterpreted. Regardless of the etymology, the name stuck and quickly became associated with something transient, unwelcome, and potentially dangerous. This set the stage for a perfect storm of fear, where a new, invasive spider became a convenient scapegoat for unexplained skin lesions.

Anatomy of a Reputation: How the Hobo Spider Became Feared

The transformation of Tegenaria agrestis from an anonymous European field spider to a notorious North American menace is a classic example of how medical entomology can sometimes get it wrong before it gets it right. In the 1970s and 1980s, medical professionals in the Pacific Northwest were dealing with skin lesions that resembled necrotic wounds. These lesions were often automatically attributed to brown recluse spider bites. There was one enormous problem with this diagnosis: the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) has a very limited native range in the central United States and is not found in the Pacific Northwest. A different culprit had to be found.

Enter the hobo spider. It was abundant, it was a newcomer, and it was often found in homes. Based on a limited number of studies that involved injecting spider venom into laboratory rabbits—a methodology now questioned due to the vast difference in tissue reaction between rabbits and humans—the hobo spider was declared the cause of these necrotic wounds. The myth was born and quickly cemented into public consciousness. Pest control companies, news media, and even public health organizations disseminated information labeling the hobo spider as a dangerous aggressor. For decades, it held the unofficial title of the “aggressive house spider” in many regions, despite its behavior being anything but aggressive towards humans.

The Science of Absolution: Modern Research on Tegenaria Agrestis

As the 21st century progressed, improved diagnostic techniques and more rigorous scientific scrutiny began to unravel the case against the hobo spider. A major breakthrough came from the field of microbiology. Doctors and researchers started to correctly identify the actual causes of many of these mysterious necrotic wounds. The vast majority were found to be infections from common bacteria, most notably Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA). Other conditions like diabetic ulcers, fungal infections, and reactions to chemicals or other arthropods like ticks and mites were also misdiagnosed as spider bites.

Critically, toxicological studies of Tegenaria agrestis venom failed to find any compounds capable of causing tissue death in humans. The venom is designed to subdue its small insect prey, not harm large mammals. Numerous studies attempting to link the spider directly to a necrotic bite have failed. In light of this overwhelming evidence, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other major medical authorities have formally removed the hobo spider from their lists of medically significant spiders. The scientific consensus today is clear: the hobo spider, or Tegenaria agrestis, is not considered a danger to humans. Its venom is not cytotoxic, and it is not the cause of the severe wounds it was once blamed for.

A Guide to Accurate Identification: Is It Really a Hobo Spider?

Even though its danger has been vastly overstated, correctly identifying Tegenaria agrestis is still useful for peace of mind and for understanding the ecology around your home. However, identification is notoriously difficult and should be left to experts with a microscope. Many harmless spiders are mistaken for hobos. The key is to look at a combination of features rather than a single trait.

First, consider the geography. If you are not in the Pacific Northwest, Idaho, Utah, or parts of Colorado and Montana, you are extremely unlikely to encounter a hobo spider. They have not spread significantly beyond these regions. Second, look at the web. Hobo spiders build a distinctive funnel web. This web has a non-sticky, sheet-like structure that leads back to a silken retreat or funnel where the spider hides, waiting for prey to stumble onto the mat. The web is often found in basements, window wells, wood piles, and other undisturbed areas.

“Misidentification is the root of most spider fear. Taking a moment to look closer often reveals a harmless, beneficial predator, not a threat.” — An Arachnologist’s Perspective

Physical characteristics require a very close look. Hobo spiders are typically brown with a distinctive herringbone pattern on the top of their abdomen, though this can be faint. Their legs are solid-colored without bold bands. The most reliable identifiers—the arrangement of their eyes and the presence of two long, glove-like palps on males—require magnification. Because so many other funnel-weaving spiders (like the giant house spider, Eratigena atrica) look nearly identical, visual identification by a novice is highly error-prone. When in doubt, assume it’s a harmless house spider and simply relocate it.

Meeting the Look-Alikes: Common Hobo Spider Doppelgangers

The world of spiders is full of convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop similar appearances. The hobo spider has several common cousins and mimics that are far more likely to be the spider you’re seeing. The most frequent imposter is the Giant House Spider (Eratigena atrica or E. duellica), another European introduction that is incredibly common in homes. It is significantly larger than the hobo, often with banded legs, and is a champion insect predator. Despite its intimidating size and speed, it is utterly harmless.

Another common confusion is with the domestic house spider (Tegenaria domestica), a close relative that builds a similar web but often has a distinctive chevron pattern on its abdomen. In regions where brown recluse spiders actually live, any medium-sized brown spider is often mistakenly called a recluse. Brown recluses have a defining dark violin-shaped marking on their cephalothorax and only six eyes arranged in pairs, unlike the hobo spider’s eight eyes in two rows. Understanding these differences is key to overcoming unnecessary fear.

The Life and Times of a Misunderstood Predator

Beyond the myths, Tegenaria agrestis has a fascinating biology. It is a hunter of the small and slow, primarily preying on insects like cockroaches, silverfish, beetles, and other spiders that become ensnared in its web. It is not an active hunter of humans and would much rather flee than confront something thousands of times its size. Its life cycle is typical of many spiders: eggs are laid in a silken sac guarded by the female, the spiderlings emerge and disperse, and they molt several times before reaching adulthood. Males typically live for about one year, dying shortly after mating. Females can live longer, sometimes for several seasons.

The dispersal method of spiderlings, known as “ballooning,” is one way the species has spread. A young spider will climb to a high point, release a strand of silk into the air, and let the wind carry it to a new location. This behavior underscores their passive nature; they are accidental invaders in homes, not deliberate aggressors. They enter structures seeking shelter and prey, not people. Their ecological role is overwhelmingly positive, as they help control populations of true pests.

Coexisting with Hobo Spiders: Practical Home Management

Knowing that the hobo spider is not a medical threat allows us to shift our strategy from eradication to management. The goal is not to eliminate all spiders—an impossible and ecologically harmful task—but to minimize unwanted encounters inside the home. The most effective method is exclusion. Sealing cracks and gaps around foundations, windows, and doors with caulk or weather stripping prevents spiders from entering in the first place.

Reducing clutter in basements, garages, and crawl spaces eliminates the sheltered, undisturbed habitats they prefer for web-building. Since they are attracted to other insects, general pest control measures like keeping food sealed, addressing moisture issues, and using exterior lighting that doesn’t attract bugs (like yellow sodium vapor lights) can reduce the prey that draws spiders indoors. If you find a funnel web, you can simply vacuum it up, spider and all. There is no need for widespread pesticide use, which poses far greater risks to human and pet health than the spiders themselves.

The Bigger Picture: Why Spider Myths Persist

The saga of the hobo spider is a powerful lesson in mass psychology and the persistence of myth. Even as scientific evidence mounts, the scary story continues to be told. This is partly due to the “availability heuristic,” a mental shortcut where people assess the likelihood of risk based on how easily examples come to mind. Gruesome images of “spider bites” online are far more memorable than a dry scientific paper exonerating the animal.

The internet acts as an echo chamber for these myths, with outdated information recirculated endlessly on pest control websites and social media. Furthermore, the need for a simple explanation is strong. “A spider bit me” is a simpler narrative than “I have a complex bacterial infection that requires a specific antibiotic.” Overcoming this requires a conscious effort to update our knowledge and trust the consensus of experts who have moved on from the outdated fears of the past.

Wolf Spider vs Brown Recluse: The Ultimate Guide to Identification, Bites, and Safety

Conclusion

The journey through the world of the hobo spider vs Tegenaria agrestis reveals a story not of a dangerous monster, but of a profound case of mistaken identity. The same spider that lives in fear-inducing infamy in North America is considered a mundane resident of fields and gardens in Europe. Modern science has systematically dismantled the myths surrounding this creature, revealing it to be a harmless, and indeed beneficial, predator of actual pests. Its venom is not a threat to human health, and its behavior is reclusive, not aggressive. The real culprit behind the wounds it was blamed for is almost always common bacteria. By understanding the facts, correctly identifying the spiders around us, and practicing simple exclusion techniques, we can replace fear with respect and learn to coexist with the intricate and helpful arachnids that share our environment.

Frequently Asked Questions Hobo Spider vs Tegenaria Agrestis:

Is a hobo spider bite dangerous to humans?

Based on current scientific consensus, no, a bite from a hobo spider (Tegenaria agrestis) is not considered dangerous to humans. Extensive research has failed to link its venom to necrotic skin lesions. While any spider bite may cause minor, temporary symptoms like redness, slight swelling, or itching—similar to a bee sting or mosquito bite—the severe wounds historically attributed to it are now known to be caused by bacterial infections like MRSA.

What is the main difference between a hobo spider and a brown recluse?

The main differences are vast. Geographically, the brown recluse is native to the central US and not found in the Pacific Northwest, which is the primary habitat of the hobo spider. Physically, the brown recluse has a distinct dark violin-shaped marking on its head and has only six eyes. The hobo spider has eight eyes and lacks this violin mark. Most importantly, the brown recluse possesses a medically significant cytotoxic venom, while the hobo spider does not.

How can I tell a hobo spider from a giant house spider?

This is very difficult without magnification. The Giant House Spider (Eratigena atrica) is a common look-alike but is typically much larger, with a larger body and longer legs. The Giant House Spider often has light bands or stripes on its legs, while the hobo spider’s legs are generally a solid brown color. The most reliable identification involves examining the reproductive organs (palps) under a microscope, a task for an arachnologist.

Why did doctors used to think hobo spiders were dangerous?

The belief originated from a combination of factors in the 1970s-80s: the need to explain necrotic wounds in regions without brown recluse spiders, preliminary rabbit-based venom studies that suggested potential for tissue damage, and the spider’s status as a common invasive species found in homes. This created a plausible, but ultimately incorrect, causal link that became entrenched in medical and pest control literature for years before better science and diagnostics could correct it.

If I find a funnel web in my basement, should I be worried?

Not necessarily. Many harmless spider species build funnel webs, including the common and beneficial house spiders. The presence of a funnel web simply indicates a spider is helping control insect pests in that area. If you wish to remove it, you can simply vacuum it up. There is no need for alarm or chemical pesticides. Focus on sealing entry points and reducing clutter to make your home less inviting to all spiders.

Comparison Table: Hobo Spider vs. Common Look-Alikes

| Feature | Hobo Spider (Tegenaria agrestis) | Giant House Spider (Eratigena atrica) | Brown Recluse (Loxosceles reclusa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size (Body Length) | 7-14 mm | 10-18 mm ( noticeably larger) | 6-20 mm |

| Leg Appearance | Solid color, no bold bands | Often has distinct banding or streaks | Solid color, long and slender |

| Key Marking | Faint herringbone pattern on abdomen | Variable, but no consistent defining mark | Dark violin-shaped marking on head |

| Eye Arrangement | 8 eyes in two curved rows | 8 eyes in two curved rows | 6 eyes in three pairs (a key identifier) |

| Web Type | Funnel web | Funnel web | Irregular, off-white tangled web |

| Geographic Range | Pacific Northwest, Utah, Colorado | Pacific Northwest, widespread in homes | Central & Southern US only |

| Venom Medical Significance | None – not considered dangerous | None – not considered dangerous | Yes – cytotoxic, can cause necrotic lesions |

| Behavior | Skittish, reluctant to bite | Fast, skittish, reluctant to bite | Reclusive, hides, bites only when pressed |