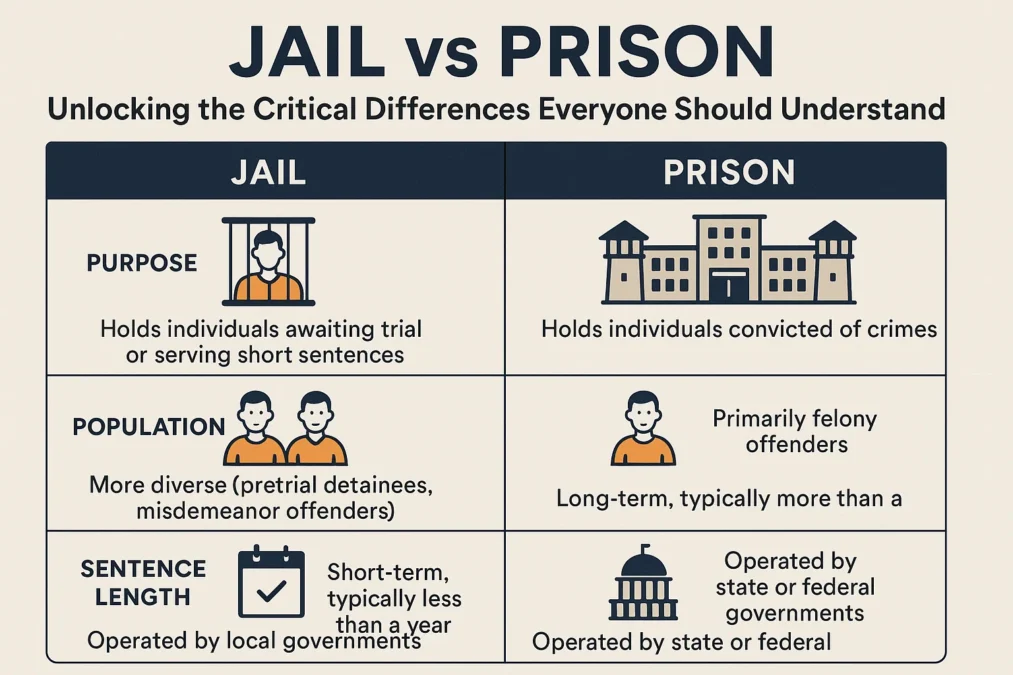

Jail vs Prison: You’ve probably heard the terms used interchangeably on the news, in movies, or in everyday conversation. A person gets arrested, and someone says, “They’re going to prison.” But is that accurate? The reality is that “jail” and “prison” refer to two fundamentally different parts of the American correctional system. Understanding the distinction between jail vs prison is more than just a matter of semantics; it’s about comprehending how our justice system operates, from the moment of an arrest to the final day of a multi-year sentence. This knowledge is crucial for defendants, their families, and any informed citizen. While both are facilities designed to incarcerate individuals, they serve distinct purposes, house different populations, and are operated by separate levels of government. Confusing the two can lead to misunderstandings about the severity of a legal situation, the length of a potential stay, and the resources available to those inside. This comprehensive guide will demystify the subject, taking you on a deep dive into the separate worlds of jail and prison, exploring everything from their primary functions and daily life within their walls to the long-lasting consequences of being incarcerated in either one. We will peel back the layers to reveal the critical distinctions that define the jail vs prison conversation.

Defining the Basics: What Exactly is a Jail?

When we talk about a jail, we are referring to a local, short-term holding facility. Jails are the front line of the correctional system, often the first place a person is taken after an arrest by local law enforcement like city police or county sheriffs. The most critical aspect of a jail is its transient nature. It’s designed for people who are in a state of legal limbo—they haven’t been convicted of a crime yet, or they are serving a very short sentence. The primary purpose of a jail is not for long-term punishment but for short-term custody. Jails are overwhelmingly operated at the county level, typically under the jurisdiction of a county sheriff’s office, though some larger cities may also operate their own municipal jails. This local control means that the conditions, policies, and resources available in a jail can vary dramatically from one county to the next.

The population inside a jail is incredibly diverse and reflects the various stages of the criminal justice process. You will find individuals who have just been arrested and are awaiting their initial court appearance, also known as an arraignment. You will also find defendants who have been charged but cannot afford to post bail, forcing them to remain in custody until their trial date. Furthermore, jails hold individuals who have been convicted of lower-level crimes, often misdemeanors, and are serving sentences that are typically less than one year. In many jurisdictions, jails also serve as a holding pen for individuals awaiting transfer to a state prison after they have been convicted and sentenced to a longer term. This creates a dynamic and often chaotic environment where the population is in constant flux, with people moving in and out daily. This constant turnover presents unique challenges for jail administration, from managing inmate mental health to preventing the spread of contagions.

Defining the Basics: What Exactly is a Prison?

In contrast, a prison is a state or federal long-term correctional facility designed for individuals who have been convicted of serious crimes, known as felonies. The key differentiator in the jail vs prison discussion is the concept of long-term confinement. Prisons are built for people who have been through the entire judicial process—they have been charged, tried, found guilty, and sentenced by a judge to a term of incarceration that is almost always more than one year, and often much longer. Sentences can range from a couple of years to multiple life sentences. The mission of a prison is fundamentally different from that of a jail. While jails focus on temporary custody, prisons are intended for punishment, rehabilitation, and the secure long-term containment of individuals deemed a significant threat to public safety.

Prisons are operated by either state governments or the federal government. State prisons house individuals convicted of violating state laws, such as murder, robbery, or aggravated assault. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) manages facilities for those convicted of federal crimes, such as bank robbery, drug trafficking across state lines, or white-collar crimes like securities fraud. Because they are designed for long-term habitation, prisons are typically much larger than jails and are often located in remote, rural areas. They are structured as self-contained communities, with their own internal security levels—minimum, medium, and maximum—that dictate the freedom of movement and the types of amenities available to inmates. The population in a prison is more stable than in a jail; people are there for years or decades, which allows for the establishment of routines, subcultures, and more structured, long-term programming, though access to these programs varies widely.

The Key Differences Between Jail and Prison in a Nutshell

To truly grasp the jail vs prison dynamic, it’s helpful to break down the core distinctions into clear, comparable categories. The most fundamental difference lies in the length of stay. Jails are for the short-term, handling stays that last from a few hours to just under a year. Prisons are for the long haul, managing inmates for years, decades, or even entire lifetimes. This difference in duration influences every other aspect of life inside, from the design of the facilities to the psychological impact on the inmates. A stay in jail is often a disruptive, stressful event, but a prison sentence represents a fundamental and long-lasting alteration of a person’s life path.

Another cornerstone of the jail vs prison distinction is the level of government control. Jails are local institutions, run by cities and counties. This means they are subject to local budgets and local political pressures. Prisons, on the other hand, are state or federal institutions. This state and federal control means they often have more standardized procedures and larger budgets, though they can be more bureaucratic and distant from an inmate’s family and community. The types of inmates housed in each facility follow directly from their purpose. Jails hold a mixed bag of pre-trial detainees and those serving short sentences for minor offenses. Prisons hold a more homogeneous population of convicted felons who have been found guilty of the most serious crimes under the law. This difference in population creates vastly different social environments and security challenges.

Who Gets Sent to Jail? A Look at the Inmate Population

The population within a county jail is a snapshot of the earliest and least severe stages of the criminal justice process. A significant portion of any jail’s population consists of pre-trial detainees. These are individuals who have been arrested and charged with a crime but have not yet had their day in court. They are legally presumed innocent, yet they remain behind bars primarily for one reason: they cannot afford to post bail. The bail system is a major driver of jail overcrowding, as low-income defendants often languish in jail for weeks or months awaiting trial for minor offenses, not because they are a flight risk or a danger to the community, but simply because they are poor. This creates a two-tiered system of justice where freedom before trial is often determined by wealth.

The other main group in a jail consists of convicted individuals serving short sentences. These are typically for misdemeanor offenses, which are less serious crimes like petty theft, simple assault, public intoxication, or trespassing. The maximum sentence for a misdemeanor is usually up to one year in a county jail. Additionally, jails hold people who are serving intermittent sentences, such as weekends, for offenses like DUI. Jails also perform other functions, such as holding material witnesses for court, people found in contempt of court, and juveniles awaiting transfer to juvenile detention facilities (though they are typically housed separately from adults). This diverse mix means that a first-time offender arrested for disorderly conduct might be housed in the same facility as a person awaiting trial for a more serious felony, leading to a potentially intimidating and dangerous environment for those not accustomed to the carceral world.

Who Gets Sent to Prison? The Felony Conviction Pathway

Admission to a state or federal prison is reserved for individuals who have been convicted of felonies. Felonies are serious crimes that are punishable by more than one year of incarceration. The path to prison is a formal and lengthy one. It begins with a formal indictment or filing of charges, proceeds through the trial process (or ends in a plea bargain), and culminates in a sentencing hearing where a judge imposes a term of imprisonment. Unlike the transient population of a jail, everyone in a prison has been found guilty of a serious offense and is there for an extended period. The types of crimes that lead to a prison sentence include violent offenses like murder, manslaughter, and rape; property crimes like burglary and arson; and drug offenses like large-scale trafficking.

The population within a prison is categorized not only by their crime but also by their security classification. Upon intake, inmates are assessed for their security level, which determines the type of prison they are sent to. Minimum-security prisons, often called prison camps, house non-violent offenders and those deemed to pose little risk of escape or violence. These facilities have fewer restrictions and may even have dormitory-style housing without armed guards or perimeter fences. Medium-security prisons hold a broader range of offenders and have stronger perimeter security, such as double fences. Maximum-security prisons, often the most famous and feared, are designed for the most violent and disruptive inmates, those with lengthy criminal histories, or those who have proven unable to function in a lower-security environment. These facilities feature constant surveillance, controlled movement, and high walls with armed towers. The federal system also includes supermax prisons, like the ADX Florence in Colorado, which represents the highest level of confinement, designed for inmates considered extremely dangerous.

A Day in the Life: The Reality of Incarceration in Jail

Life in a county jail is often characterized by boredom, uncertainty, and a lack of structure. For pre-trial detainees, the days can blend together in a monotonous cycle with little to do. Inmates typically spend most of their time in their cells or in a common dayroom. The day usually starts very early with a wake-up call, followed by a meager breakfast that might be served in the cell or in a common area. Because jails are not designed for long-term rehabilitation, programming is extremely limited. There may be no access to educational classes, vocational training, or substantial recreational activities. Inmates might have access to a small library cart, a television in the dayroom, and perhaps a chance to make a phone call or have a visit, but these privileges are often scarce and highly regulated.

The environment in a jail is typically more tense and volatile than in a prison. The constant influx and outflow of new people create instability. Inmates are often dealing with the acute stress of their legal situation—worrying about their family, their job, and the outcome of their case. This anxiety, combined with idleness, can lead to short tempers and conflicts. Medical and mental health care in jails is often criticized for being inadequate; many inmates enter with pre-existing conditions or substance withdrawal issues that are not properly addressed. The food is basic and unappealing, and hygiene products are limited. The overarching feeling in a jail is one of waiting—waiting for a court date, waiting for a lawyer, waiting for a plea deal, or just waiting for the days to pass until release.

A Day in the Life: The Structured Existence in Prison

In contrast, life in a state or federal prison is highly structured and regimented. While still punitive and difficult, the long-term nature of a prison sentence means that the institution operates on a strict, predictable schedule. Inmates have assigned jobs, such as working in the kitchen, laundry, or maintenance crews, for which they are paid a very small wage, often just cents per hour. This work provides some structure to the day and a meager source of income for commissary items like snacks, hygiene products, or writing materials. The day is broken up by head counts, meals in a central cafeteria, and scheduled times for recreation in a yard or gym.

Because inmates are serving long sentences, prisons offer more opportunities for programs, though their quality and availability vary significantly by institution. Inmates may be able to earn their GED, take college courses through partnerships with local universities, or participate in vocational training for trades like plumbing, carpentry, or barbering. There are also rehabilitative programs focused on substance abuse, anger management, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Access to the prison library is more robust, and recreational sports leagues are common. However, this structured existence comes with its own challenges. The social hierarchy in prison is rigid and complex, often based on the nature of one’s crime, gang affiliations, and length of sentence. Violence, while not constant, is an ever-present threat, and inmates must learn to navigate this social landscape carefully to survive their sentence. The long-term separation from family and the outside world leads to profound loneliness and psychological strain.

Sentencing and Time Served: How Long You Stay

The length of incarceration is the most straightforward differentiator in the jail vs prison comparison. A sentence to jail is, by definition, short-term. By law, a jail is authorized to hold individuals for a maximum of one year, though most stays are far shorter. Many people in jail on misdemeanor charges serve sentences of a few days, weeks, or months. For pre-trial detainees, the length of stay is determined not by a sentence, but by the speed of the court system. It can take months for a case to go to trial, and during that entire time, an innocent-until-proven-guilty defendant may be sitting in a jail cell. Time served in jail is almost always applied to any subsequent prison sentence, meaning if someone is held in jail for six months before being convicted and sentenced to five years in prison, those six months will be deducted from their prison term.

A prison sentence, by contrast, is measured in years. Sentences can range from a year and a day to multiple life sentences without the possibility of parole. Some states still have the death penalty, for which inmates are held in special confinement units within prison. Within the prison system, the concept of “good time” is crucial. Inmates can often have their sentences reduced for good behavior and for participating in required programs. In the federal system, for example, inmates can earn up to 54 days of good time credit for each year of their sentence. Parole, which is the conditional early release of a prisoner, is another factor. While the federal system and some states have abolished parole, in others, a parole board determines if an inmate is ready to be released back into the community under supervision before their full sentence is complete. This creates an incentive for inmates to follow the rules and engage in rehabilitative efforts.

Facility Design and Security Levels

The physical design of jails and prisons reflects their distinct purposes. Jails are typically located within urban or suburban areas to provide easy access for courts, lawyers, and law enforcement. They are often high-rise buildings or compact complexes designed for maximum efficiency in processing and holding a transient population. Security in a jail is focused on internal control. Cells are often arranged in “pods” or “tanks” surrounding a central control station where officers can monitor all activity. Because the population is unpredictable and includes many people who are volatile due to recent arrest or substance withdrawal, the emphasis is on preventing fights, suicide, and vandalism within the facility.

Prisons, designed to house inmates for decades, are built like fortresses, often sprawling across large tracts of land in rural areas. The security focus is both internal and external—preventing violence among inmates while also preventing escapes. Security levels dictate the architecture. Minimum-security facilities may look more like a campus, with dormitories and minimal fencing. Medium-security prisons have reinforced perimeter fences, often with razor wire. Maximum-security prisons are the most imposing, with high concrete walls, electronic detection systems, armed guard towers, and multiple layers of locked gates. Movement within a maximum-security prison is heavily controlled; inmates are often shackled when moved outside their cellblock, and every action is monitored by cameras and correctional officers. The design is intended to neutralize the threat posed by the nation’s most dangerous offenders.

The Long-Term Impact: How Jail and Prison Shape Futures

Regardless of the facility, any period of incarceration carries a stigma that can haunt an individual long after their release. However, the long-term impact of a prison sentence is generally more severe and far-reaching than that of a jail sentence. A stint in jail for a misdemeanor, while disruptive, may not completely derail a person’s life. They may be able to return to their job, their home, and their family with relative ease, though they will still have a criminal record that can affect employment and housing opportunities. The shorter, more localized nature of a jail sentence often means community ties are not completely severed.

A felony prison sentence, on the other hand, is life-altering. The long absence severs family bonds, with high rates of divorce and estrangement from children. Upon release, formerly incarcerated people face a daunting array of “collateral consequences” that are legally imposed restrictions that limit or prohibit people with criminal records from accessing employment, occupational licenses, housing, voting, education, and other opportunities. Finding a job with a felony record is exceptionally difficult, and in many states, certain felony convictions result in a permanent loss of the right to vote. The psychological impact of years spent in a violent, hyper-vigilant environment can also lead to institutionalization, where an individual becomes so accustomed to the rigid structure of prison that they struggle to function in the free world. The social and economic toll of a prison sentence extends to families and communities, creating cycles of disadvantage that are difficult to break.

Rehabilitation and Reentry Programs

The approach to rehabilitation and preparing inmates for release is another area where the jail vs prison comparison reveals significant differences. Jails, due to their short-term and transient population, offer very little in the way of meaningful rehabilitation. The primary goal is custodial: to hold people safely and securely until their court date or until their short sentence is complete. Some larger, more progressive jails may offer basic GED classes, substance abuse detoxification, or brief counseling sessions, but these are the exception rather than the rule. The chaotic and uncertain environment of a jail is not conducive to the sustained effort required for effective rehabilitation.

Prisons, with their stable, long-term population, have a greater capacity and mandate to provide rehabilitative programming. The stated goal of most state and federal prison systems is not just to punish but also to rehabilitate. As a result, they offer a wider, though often underfunded, array of programs. These can include full high school and college degree programs, extensive vocational training, and intensive therapy for sex offenders or substance abusers. The quality and availability of these programs vary wildly from state to state and from one prison to another. The reentry process—preparing an inmate for release—is a formal part of a prison sentence. Inmates may be transferred to a lower-security “reentry” facility in the years or months leading up to their release date, where they can participate in work-release programs, gradually reintegrating into society. Despite these efforts, many argue that the system is still failing, as high recidivism rates indicate that a large percentage of released prisoners are rearrested within a few years of their release.

How to Explain Democrat vs Republican to a Child A Simple Guide for Parents

A Comparative Glance: Jail vs Prison at a Glance

The following table provides a clear, side-by-side summary of the key distinctions we’ve explored in the jail vs prison discussion.

| Feature | Jail | Prison |

|---|---|---|

| Operator | Local (County or City) | State or Federal Government |

| Inmate Status | Pre-trial detainees & those serving short sentences (<1 year) | Convicted and sentenced felons (1+ years) |

| Length of Stay | Short-term (hours to under 1 year) | Long-term (1 year to life) |

| Types of Crimes | Misdemeanors & pre-trial detention for felonies | Felonies |

| Primary Purpose | Temporary custody, awaiting trial or sentencing | Punishment, rehabilitation, long-term containment |

| Facility Design | Often urban, smaller, focused on internal control | Often rural, large campuses, multiple security levels |

| Programs | Minimal, if any (e.g., limited library, AA meetings) | More extensive (e.g., GED, college, vocational training) |

| Security Level | Generally uniform high security within the facility | Varies (Minimum, Medium, Maximum, Supermax) |

Voices from the Inside: Perspectives on Incarceration

To understand the human experience behind the jail vs prison definitions, it’s valuable to consider the perspectives of those who have lived it.

A former county jail inmate might reflect on the sheer unpredictability: “Jail is purgatory. You’re stuck in a holding pattern with no control over your life. The noise is constant, the fear is real, and you’re just counting down the minutes until you see a judge or your sentence is up. It’s a pressure cooker of anxiety.”

In contrast, a person who served a decade in a state prison might describe a different kind of struggle: “Prison is a different world. You have to learn a new set of rules to survive. The silence in max can be deafening. You make a life in there, a routine, but you watch yourself change. The hardest part isn’t the time you’re in, it’s realizing how much of the outside world has moved on without you when you get out.”

These quotes highlight the fundamental psychological difference: jail is often a chaotic and acute crisis, while prison is a slow, grinding marathon that reshapes a person’s identity.

Navigating the Legal Process

For a defendant and their family, understanding whether a loved one is in jail or prison provides critical insight into where they are in the legal process. If someone is in a county jail immediately after an arrest, it means they are at the very beginning. The immediate goals are to get them out on bail, ensure they have legal representation, and prepare for the initial hearings. The focus is on the local county court system. Communication is often more accessible, as jails are closer to family homes, though phone calls can be prohibitively expensive.

Discovering that a person has been moved to a state or federal prison signifies that the trial phase is over. They have been convicted and sentenced. The legal focus then shifts from fighting the charges to navigating the appeals process and the Department of Corrections system. For families, this often means dealing with a facility that is far from home, making visits difficult and costly. The rules for communication—phone calls, letters, and email—are dictated by the specific state or federal prison system and can be complex. Knowing the difference helps families set expectations, understand the timeline, and provide the appropriate support at each stage.

Conclusion

The distinction between jail and prison is a critical one, rooted in the very structure of the American justice system. While both involve the loss of liberty, they serve fundamentally different purposes. A jail is a local, short-term holding facility for the accused and those serving brief sentences for minor crimes. It is a place of uncertainty and transition. A prison is a state or federal, long-term institution for those convicted of serious felonies, designed for punishment and rehabilitation over many years. Understanding the jail vs prison difference—in their operation, populations, daily life, and long-term consequences—empowers us to be more informed citizens, better support those navigating the system, and engage in more meaningful conversations about criminal justice reform. It is not just a matter of vocabulary; it is about understanding two separate worlds of incarceration that impact millions of lives.

Frequently Asked Questions About Jail vs Prison

What is the main difference between jail and prison?

The main difference between jail and prison boils down to the length of stay and who operates them. Jails are local, short-term facilities (for stays under one year) housing pre-trial detainees and those serving sentences for misdemeanors. Prisons are state or federal, long-term facilities (for stays of one year or more) for individuals convicted of felonies.

Can you go to prison without going to jail?

Yes, it is possible, though not the most common path. Typically, after an arrest, a person is taken to jail. If they are convicted of a felony and sentenced to a state or federal prison term, they are then transferred from jail to prison. However, someone who is out on bail or own recognizance before their trial would not be in jail pre-trial. If they are then convicted and sentenced to prison, they would go directly to prison without having been in jail first, though they would have been booked into a jail initially upon arrest.

Are conditions worse in jail or prison?

This is subjective and depends on the specific facilities being compared. Jails are often described as more chaotic, stressful, and boring due to the transient population and lack of programming. Prisons, especially maximum-security ones, can be more violent and restrictive, but they also offer more structure and long-term programs. Many inmates report that the uncertainty and idleness of jail make it psychologically difficult, while the long-term isolation and rigid social structure of prison present their own severe challenges.

How do visitation rights differ between jail and prison?

Visitation in both jail and prison is a privilege, not a right, and is highly regulated. Jail visits are often shorter and may be conducted through video screens rather than in-person contact visits due to space and security constraints. Prison visitation policies are more formalized and can vary by security level. Lower-security prisons may allow for contact visits in a visiting room, while maximum-security facilities might require non-contact visits with a physical barrier. Both systems require visitors to be on an approved list and subject to search.

What happens to someone after they are sentenced?

If someone is in jail for a misdemeanor and receives a sentence of less than a year, they will typically serve that entire sentence in the same county jail. If someone is convicted of a felony and sentenced to a term in state or federal prison, they are remanded back to jail to await transfer. They will be processed through a state reception and classification center where they are assessed for their security level and then assigned to a specific prison facility to serve their sentence. The time they already spent in jail pre-trial is almost always credited toward their total prison sentence.