You’re facing a legal issue. Maybe it’s a contract dispute, a traffic ticket, or the complex paperwork of starting a business. You know you need professional help, but who do you call? The terms “lawyer” and “attorney” are thrown around interchangeably in movies, TV shows, and everyday conversation. It leads to a common and understandable point ofLawyer vs Attorney confusion: is there actually a difference between a lawyer and an attorney? If you were to walk into a legal firm, would you be making a mistake by using one title over the other?

The short answer is that in modern, casual conversation, the difference is often negligible. Most people use them as synonyms, and in many situations, that’s perfectly acceptable. However, when you dive into the precise, detail-oriented world of law, distinctions do exist. Understanding these nuances is more than just a semantic exercise; it can provide insight into the qualifications, roles, and scope of practice of the legal professional you are considering hiring. This article will serve as your definitive guide, dissecting the historical roots, formal definitions, and practical applications of these two titles. We will explore the educational path all legal professionals share, the critical point where their paths diverge, and what it all means for you as a potential client seeking justice, guidance, or representation.

The Heart of the Matter: Core Definitions

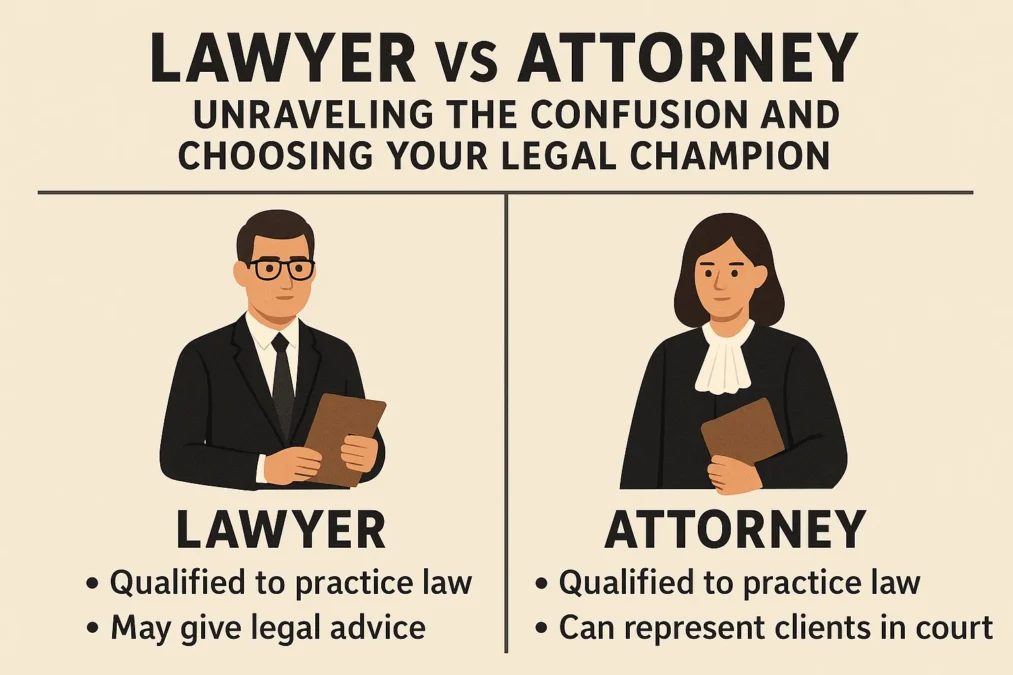

To build our understanding from the ground up, we must start with clear, dictionary-backed definitions. While these definitions highlight the technical difference, they also reveal why the confusion is so prevalent. Both roles are deeply rooted in the law, requiring a significant investment in education and training. The key differentiator often lies in one specific action: practicing in court on someone else’s behalf.

A lawyer is a person who has been trained in the law and has graduated from law school. In essence, anyone who holds a Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree is a lawyer. The term itself comes from the Middle English word meaning “one versed in law.” Think of “lawyer” as a broad, umbrella term. It describes an individual who has the knowledge and education of the legal system. This person can provide legal advice, draft legal documents, and guide clients through complex legal processes. However, simply being a lawyer does not necessarily grant them the right to represent a client in every legal forum, particularly a court of law. They are a legal scholar and advisor, equipped with the theoretical and practical knowledge of jurisprudence.

An attorney, on the other hand, is a specific type of lawyer. The word “attorney” comes from the French word ‘attorné,’ meaning “one appointed to act for another.” This etymology points directly to the core function. An attorney is a lawyer who has passed the bar examination in a specific jurisdiction and has been licensed by the state bar association to practice law. This licensure grants them the right to represent clients in court, to file lawsuits on their behalf, and to act as a formal legal agent. Essentially, all attorneys are lawyers, but not all lawyers are attorneys. An attorney has taken the extra, crucial step beyond education to gain official state sanction to advocate in legal proceedings.

A Journey Through Words: The Historical Etymology

Language is a living, evolving entity, and the history behind the words “lawyer” and “attorney” reveals a great deal about why we have two terms for seemingly similar professions. The distinction we see today is a relic of a more precise linguistic past, one that has blurred over time but still informs the formal definitions. Understanding this history enriches our comprehension of the legal field’s traditions and its roots in older systems of governance and society.

The term “lawyer” has a more straightforward Anglo-Saxon origin. It simply denotes a person who practices or studies law. It was the common term used in England and early America to describe anyone involved in the legal trade. “Attorney,” however, has a more nuanced history rooted in the English feudal system. It was initially used to describe any person who held a power of attorney—a legal document that authorizes one person to act on behalf of another in business or legal matters. Over centuries, as the legal profession became more formalized, the term “attorney at law” emerged in the United States to distinguish a specialized legal agent from a general agent. This was the person you “turned” your case over to, your formal representative in the courts of law.

This historical context explains why “attorney” carries a connotation of action and representation, while “lawyer” is a broader descriptor of occupation. In the United Kingdom, the term “solicitor” (who handles legal matters outside court) and “barrister” (who represents clients in court) created a clear division of labor. American English simplified this, but the legacy remains in the dual terms of lawyer and attorney, with “attorney” often implying the court-room advocate. This linguistic journey from feudal England to modern American courtrooms shows how the practical needs of clients shaped the very titles we use to describe our legal champions.

The Shared Path: Education and the Juris Doctor Degree

Before anyone can claim the title of lawyer or aspire to become an attorney, they must navigate a rigorous and demanding educational journey. This path is universal; whether a person aims to be a corporate legal advisor (a lawyer) or a criminal prosecutor (an attorney), the foundational training is identical. It is this shared experience that creates the primary reason for the terms’ interchangeability in everyday language. The academic and intellectual hurdle of law school is the common crucible for all legal professionals.

The first step is an undergraduate degree. Unlike medical school, which has specific prerequisite courses, law schools accept students from virtually any major. Common pre-law paths include Political Science, History, English, and Philosophy, but it’s not unusual to see engineers, biologists, or artists in a law school classroom. The key is developing strong critical thinking, analytical reasoning, and communication skills. After obtaining a bachelor’s degree, the aspiring legal professional must take the Law School Admission Test (LSAT), a standardized test that assesses reading comprehension and logical reasoning. LSAT scores and undergraduate GPAs are the primary factors in law school admissions.

Once admitted, the student embarks on a three-year full-time program to earn a Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree. The first year (1L) is typically the most standardized, covering foundational courses like Civil Procedure, Constitutional Law, Contracts, Torts, Property, and Criminal Law. The second and third years (2L and 3L) allow for specialization through electives in areas such as intellectual property, environmental law, or international law. Throughout this period, students learn to “think like a lawyer”—a process that involves analyzing complex problems, constructing logical arguments, and understanding legal precedent. Upon graduation, the individual is a lawyer. They have the knowledge. But to actively practice law and represent clients, they must clear one more, significant hurdle.

The Critical Divider: The Bar Examination and Licensure

This is the great divider, the line in the sand that separates a lawyer from an attorney. Graduating from law school confers the title of “lawyer,” but it does not grant a license to practice law. The ability to represent clients in court, to give legally binding advice, and to file official legal documents is a privilege regulated by individual state governments. The barrier to entry for this privileged practice is the bar examination, a notoriously difficult test that serves as the gateway to becoming an attorney.

The bar exam is a multi-day ordeal that tests a candidate’s knowledge of general legal principles and the specific laws of the state in which they intend to practice. It often includes the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE), a standardized section, as well as essay questions and performance tests designed to simulate real-world legal tasks. The intensity of preparation for this exam is immense, with many graduates dedicating two to three months of full-time study after law school. Passing the bar is a monumental achievement, but it’s not the final step. Candidates must also pass a character and fitness evaluation, which scrutinizes their moral background and financial responsibility to ensure they are fit to be officers of the court.

Once a lawyer has passed the bar exam and the character and fitness review, they are officially admitted to the bar of that state. They are now an attorney at law. They can legally represent clients, appear in court, and are bound by the rules of professional conduct enforced by the state bar association. This licensure is what transforms theoretical knowledge into practical, actionable authority. A person who has graduated law school but has not passed a bar exam cannot represent you in court or provide official legal counsel. They are a lawyer by education, but not an attorney by licensure.

Exploring the Legal Landscape: Other Key Titles and Roles

The legal field is rich with specialized titles, which can further complicate the “lawyer vs attorney” discussion. Understanding these roles provides a clearer picture of the legal ecosystem and where our two main titles fit within it. Two of the most common titles you will encounter are “esquire” and “counselor,” each with its own specific meaning and context. Recognizing these terms will make you a more informed consumer of legal services.

Esquire (Esq.) is a professional title often used by attorneys in the United States. Historically, it was a title of courtesy in England, but in the U.S., it is typically appended to a lawyer’s name (e.g., Jane Doe, Esq.) to indicate that they are a licensed attorney who has passed the bar exam. Its use is a clear signal that the individual is not just a law school graduate, but a practicing member of the bar. Then there is counselor (or “counselor at law”). This term is often used in a courtroom setting; a judge might address an attorney as “counsel.” It emphasizes the attorney’s role as an advisor and advocate. When you hire an attorney, they serve as your counselor, providing strategic advice and guiding you through your legal options.

Beyond these, you have specialized roles like solicitor and barrister, which are standard in countries like the U.K. but not in the U.S. A solicitor is a lawyer who handles legal matters outside of court, such as drafting contracts and wills, while a barrister is a lawyer who specializes in courtroom advocacy. In the U.S., an attorney is generally qualified to perform both roles. Another common title is in-house counsel. These are lawyers who are employed by a single corporation to handle its legal affairs. They are almost always licensed attorneys, making them attorneys in every sense of the word, but their “client” is their employer. Understanding this landscape shows that while “lawyer” is the broadest term, the specific title used can tell you a lot about a person’s role, licensure, and specialization.

DWI vs DUI: The Ultimate Guide to Understanding the Difference and Protecting Your Rights

Practical Implications: When the Distinction Matters to You

For the average person seeking legal help, does the difference between a lawyer and an attorney really matter? In most initial consultations, probably not. If you walk into a law firm and ask to speak to a lawyer, you will almost certainly be directed to a licensed attorney. However, there are specific, high-stakes scenarios where understanding this distinction is not just academic—it’s critical to the success of your case. Knowing the limits of a professional’s license can protect you from unauthorized practice of law and ensure you have the right advocate for your specific battle.

The most obvious scenario is courtroom litigation. If you are being sued or need to file a lawsuit, the person representing you must be an attorney. They must be a member of the bar in the state where the court is located. A non-attorney lawyer, meaning someone with a J.D. who has not passed the bar, is prohibited from appearing before a judge on your behalf, filing legal briefs, or presenting evidence. Allowing someone who is not a licensed attorney to do this could have disastrous consequences for your case and could even be considered a violation of court rules. For any matter that involves a courtroom, you need an attorney.

Another critical area is the provision of formal legal advice. While a non-attorney lawyer might understand the law, providing official legal counsel that you rely upon is typically considered the practice of law, which requires a license. This is crucial in situations like drafting a will that must be probated, negotiating a complex business merger, or providing a definitive interpretation of a statute that affects your rights. For these formal, binding matters, you need the expertise and official sanction of an attorney. However, for more general legal information—such as a law professor explaining a legal concept or a legal document reviewer analyzing contracts for a company without giving final advice—a lawyer may be perfectly suited for the task. The key is the action and the reliance; when your liberty, finances, or property are on the line based on a legal opinion, that opinion must come from an attorney.

The Modern Blur: Why the Terms Are Used Interchangeably

Despite the clear technical distinctions we’ve outlined, the reality is that in 21st-century American English, “lawyer” and “attorney” have largely merged in common usage. This isn’t a mistake made by the public; it’s a natural evolution of language, heavily influenced by cultural and professional practices. The legal community itself often uses the terms loosely, contributing to the blurring of the lines. Understanding why this happens can help you navigate the legal world without anxiety over which term to use.

The primary reason is that the vast majority of people who graduate from law school do, in fact, go on to pass the bar exam and become licensed attorneys. The career path for a J.D. graduate overwhelmingly leads to licensure. Therefore, when people interact with a legal professional, they are almost always interacting with an attorney. The likelihood of encountering a law school graduate who is not licensed is relatively low in a typical client-facing setting. This practical reality makes the distinction irrelevant for most everyday interactions. Furthermore, within law firms and corporate legal departments, colleagues may refer to each other as “lawyers” as a general professional title, regardless of whether they are discussing a court appearance or a back-office document review.

Popular culture and media have also played a massive role in cementing the terms as synonyms. Television shows, movies, and news reports use “lawyer” and “attorney” interchangeably. There is no concerted effort by scriptwriters or journalists to make a technical distinction, as it would sound stilted and unnatural to the audience. This constant exposure trains the public to see the two words as perfect substitutes. For all intents and purposes, in casual conversation, asking for a “good lawyer” is the same as asking for a “good attorney.” The important thing is that you are seeking a qualified legal professional, and the person you find will almost certainly be both.

Choosing Your Champion: What to Really Look For

Now that we’ve demystified the titles, let’s focus on what truly matters: finding the right legal professional for your specific needs. The label on their business card—whether it says “Lawyer” or “Attorney at Law”—is far less important than their experience, expertise, and your comfort level with them. Your choice of legal representation can have a profound impact on the outcome of your case and your overall experience navigating the legal system. Here is a practical guide on what to prioritize.

First and foremost, specialization is key. The law is vast and complex. You wouldn’t see a cardiologist for a broken foot. Similarly, you shouldn’t hire a divorce attorney to handle a patent application. Look for a professional whose practice area aligns directly with your problem. Do they specialize in family law, criminal defense, personal injury, corporate law, or estate planning? Review their website, their professional profiles, and their case history. Many attorneys offer free initial consultations; use this opportunity to ask pointed questions about their experience with cases exactly like yours. This is more critical than whether they primarily refer to themselves as a lawyer or an attorney.

Secondly, assess their communication and rapport. The attorney-client relationship is built on trust and clear communication. During your initial meeting, do you feel heard? Do they explain complex legal concepts in a way you can understand, without resorting to excessive jargon? Are they responsive to your calls and emails? You need a champion who will not only fight for you but also keep you informed and involved in the process. Finally, consider their reputation and track record. Look for online reviews, ask for references, and check with your state’s bar association to ensure they are in good standing and have no record of disciplinary actions. The right legal professional for you is the one who has the specific expertise you need, communicates effectively, and has a proven history of success and ethical practice.

A Side-by-Side Comparison

To help visualize the core differences and similarities, here is a comparative table:

| Feature | Lawyer | Attorney |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | A person trained in law (J.D. degree holder). | A licensed lawyer who can represent clients in court. |

| Etymology | From Middle English, meaning “one versed in law.” | From French ‘attorné,’ meaning “one appointed to act for another.” |

| Education | Requires a Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree from law school. | Requires a Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree from law school. |

| Licensure | Does not require passing the bar exam. | Must pass the state bar exam and character review. |

| Court Representation | Cannot represent clients in court. | Is legally authorized to represent clients in court. |

| Scope of Practice | Can provide legal advice, draft documents, and conduct research. | Can provide legal advice, draft documents, conduct research, and litigate. |

| Key Takeaway | The broader, umbrella term for anyone with a law degree. | A specific type of lawyer who is a licensed practitioner. |

Voices from the Field

To add depth and perspective, here are some quotes that encapsulate the nuances of this topic.

“While all attorneys are lawyers, the title of ‘attorney’ signifies a commitment to the rigorous standards of the bar and the privilege of serving as an officer of the court. It’s a distinction of both qualification and responsibility.” – A State Bar Association Ethics Committee Member.

“In daily practice, my clients call me their lawyer, and my colleagues and I use the term interchangeably. The technical difference is real, but what truly matters to the public is finding someone competent and trustworthy to handle their legal affairs.” – Sarah Chen, Partner at a Civil Litigation Firm.

“The distinction between a lawyer and an attorney is a foundational concept in legal ethics. It defines who is authorized to act as an agent in our legal system. When you see ‘Esq.’ after a name, you know that person has been vetted and sworn to uphold the law.” – Professor David Miller, Constitutional Law Scholar.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between a lawyer and an attorney?

The main difference lies in licensure to practice law in court. A lawyer is anyone who has graduated from law school with a Juris Doctor degree. An attorney is a lawyer who has also passed the bar exam in their state and has been licensed to represent clients, practice law, and appear in court. All attorneys are lawyers, but not all lawyers are attorneys.

Can a lawyer give me legal advice if they are not an attorney?

This is a complex area. A non-attorney lawyer has the knowledge to understand the law, but formally providing legal advice that you are meant to rely upon is generally considered the “practice of law,” which requires a license. For unofficial, general information, it may be fine, but for any serious matter affecting your rights or property, you should always seek counsel from a licensed attorney to ensure the advice is legally sound and the individual is accountable to the bar association.

Which term should I use when I need to hire someone?

In everyday use, you can use the terms “lawyer” and “attorney” interchangeably. The legal professional you contact will understand what you mean. When searching online or in directories, both terms will generally yield the same results—licensed legal practitioners. It is far more important to focus on finding a professional who specializes in the area of law relevant to your problem than to worry about which title to use.

Is “Esquire” the same as an attorney?

Yes, in the United States, the title “Esquire” (often abbreviated as “Esq.”) is typically used to denote that a person is a licensed attorney. When you see it appended to a name (e.g., “Robert Jones, Esq.”), it is a clear indicator that the individual has passed the bar exam and is a practicing attorney.

Do I need an attorney for matters that don’t go to court?

Often, yes. Even for matters that you hope will never see a courtroom, such as drafting a will, forming a corporation, or negotiating a contract, you need a licensed attorney. These tasks constitute the practice of law. An attorney ensures the documents are legally sound and binding, protecting you from future disputes or liabilities. Their official licensure also provides you with recourse through the state bar if something goes wrong.

Conclusion

The journey through the nuanced world of “lawyer vs attorney” reveals a landscape where technical precision and common usage coexist. While a clear, formal distinction exists—a lawyer is educated in the law, and an attorney is licensed to practice it—this difference has largely faded in the public eye for a good reason. The vast majority of legal professionals you encounter will be both. They have the J.D. degree and the bar license, embodying both titles simultaneously.

Therefore, while it is intellectually satisfying to understand the historical and technical nuances, your energy as a potential client is best spent not on semantics, but on substance. Focus on finding a legal professional with the right specialization, a proven track record, and a communication style that makes you feel confident and supported. Whether you call them your lawyer or your attorney, what you are truly seeking is a knowledgeable guide, a strategic advocate, and a trusted champion for your legal journey. That is the professional who will make the real difference in your case.