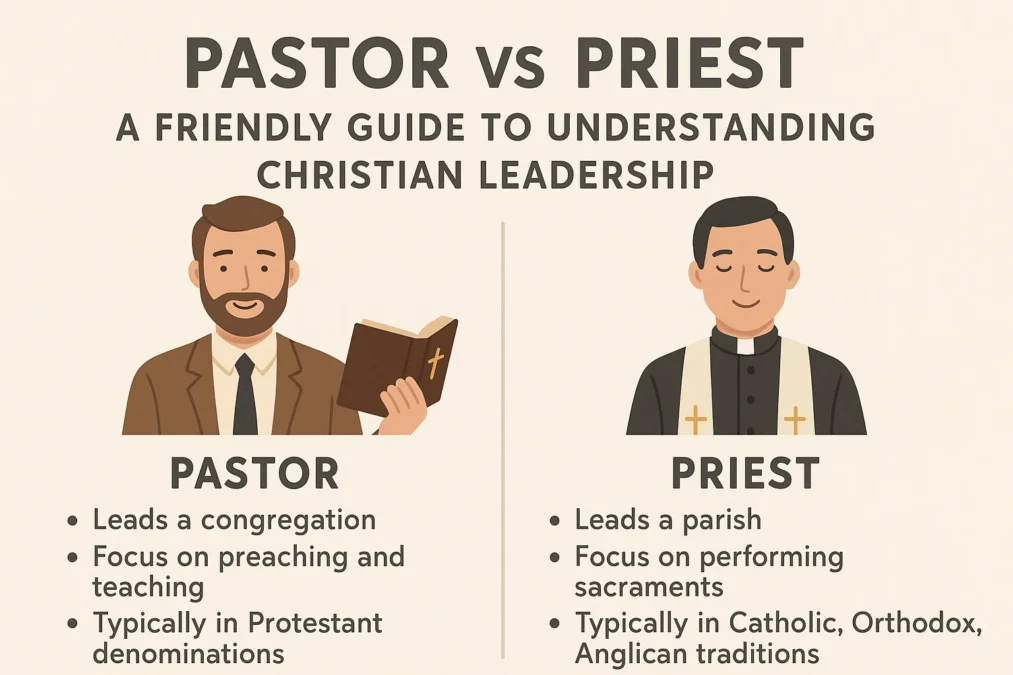

You’re sitting in a coffee shop with a friend, and they mention they’re going to see their “pastor” for counseling. Later that week, another friend talks about a beautiful mass led by their “priest.” It might get you wondering: aren’t they basically the same thing? Both are Christian leaders, both wear special clothing sometimes, and both seem to be central figures in their religious communities. While the titles “pastor” and “priest” are often used interchangeably in casual conversation, they represent distinct roles, traditions, and theological understandings within the vast and diverse family of Christianity. Understanding the difference between a pastor and a priest is more than just a matter of vocabulary; it’s a window into the history, structure, and core beliefs of different Christian denominations.

This journey into the world of Christian ministry isn’t about deciding which role is better or more correct. Instead, it’s about appreciation. By exploring the nuances of the pastor vs priest dynamic, we can gain a deeper respect for the various ways Christians organize their spiritual lives, understand authority, and seek a connection with the divine. This exploration will take us from the ancient, sacramental traditions of Catholicism and Orthodoxy to the more contemporary, preaching-focused communities of Protestantism. We will delve into their historical origins, their day-to-day responsibilities, their paths to ordination, and even how they view the very nature of church leadership. So, whether you’re a curious seeker, a person of faith looking to clarify your own understanding, or someone who just wants to know the score, this comprehensive guide is for you. Let’s begin by tracing these roles back to their roots, where the first major distinctions began to emerge.

The Historical and Theological Roots of the Divide

To truly grasp the difference between a pastor and a priest, we have to take a trip back in time, long before there was a Protestant church or a Catholic church in the way we think of them today. For the first thousand years of Christianity, the unified church was structured around bishops, priests, and deacons—an order that remains central to Catholic, Orthodox, and some Anglican and Lutheran traditions today. The word “priest” itself is actually a contraction of the Greek word “presbyteros,” which simply means “elder.” In the early church, these elders were leaders of local communities, working under the oversight of a bishop. Their role was to teach, lead worship, and shepherd the flock. The theological understanding of this role, however, would become the great fault line in the pastor vs priest discussion.

The monumental event that forever cemented the distinction was the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Reformers like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli challenged many of the doctrines and practices of the Western Church, which was centered in Rome. A central tenet of the Reformation was the “priesthood of all believers,” a concept derived from passages in the New Testament like 1 Peter 2:9. This doctrine asserted that all faithful Christians have direct access to God through Jesus Christ and do not require a human mediator. This was a direct challenge to the Catholic understanding of the ordained priest as a necessary mediator who, through the sacrament of Holy Orders, was given a special character to channel God’s grace, most importantly in the Eucharist. The Reformers saw this as creating an unnecessary and unbiblical barrier between the individual and God.

Consequently, Protestant traditions intentionally moved away from the term “priest,” feeling it carried too much baggage of a mediatorial class. They revived the more general term “pastor,” which comes from the Latin word for “shepherd.” This was a conscious theological choice. It emphasized the leader’s role as a guide, a teacher, and a caregiver for the congregation—the “flock”—rather than as a sacred mediator offering sacrifices on their behalf. This shift in terminology reflected a massive shift in ecclesiology, or the theology of the church itself. So, when we talk about a pastor vs priest, we are often talking about a divide that is nearly five hundred years old, rooted in fundamentally different views on how God’s grace is delivered to humanity and how the church should be organized.

The Core Role of a Priest in Sacramental Ministry

When you step into a Catholic, Orthodox, or high-church Anglican service, the role of the priest is central, defined, and deeply sacramental. The primary identity of a priest is that of a mediator and a custodian of the sacred mysteries, particularly the Eucharist, which is considered the source and summit of the Christian life. In these traditions, the Eucharist is not merely a symbolic memorial of Jesus’ last supper; it is the literal body and blood of Christ, made present through the miracle of transubstantiation (in Catholicism) or a similar sacred mystery (in Orthodoxy). Only a validly ordained priest has the authority to consecrate the bread and wine, to call down the Holy Spirit, and to make this sacrifice present for the people. This is the most profound and irreplaceable function of the priest.

Because of this sacramental focus, the daily life of a priest is structured around the rituals and rites of the church. Beyond celebrating Mass, he administers other sacraments that are seen as channels of God’s grace. He hears confessions and offers absolution, anoints the sick and dying, and performs baptisms and marriages. His role is often described in sacrificial language, hearkening back to the priests of the Old Testament who offered sacrifices in the Temple. In the New Covenant, the priest offers the sacrifice of the Mass. This role requires a specific, indelible spiritual character that is believed to be conferred upon him during his ordination through the sacrament of Holy Orders. This character sets him apart, not as a better person, but as one configured to Christ in a specific way to act in persona Christi (in the person of Christ) for the sake of the community. The authority of a priest is therefore derived from his place within the apostolic succession—an unbroken line of laying on of hands from the original apostles to the bishops and down to the priests of today.

The Core Role of a Pastor in Teaching and Preaching

In most Protestant traditions, the role of a pastor is shaped by the Reformation principle of the priesthood of all believers. The pastor is not a mediator who offers sacrifices but is first and foremost a teacher, a preacher, and a shepherd. The central act of worship in many Protestant churches is not the Eucharist (though it is still important) but the preaching of the Word. The sermon is the highlight of the service, where the pastor breaks open the Scriptures, explains their meaning, and applies them to the everyday lives of the congregation. The title “pastor” itself evokes this image of a caring shepherd who guides, protects, and nourishes his flock spiritually through biblical instruction and pastoral care.

The day-to-day work of a pastor, therefore, looks somewhat different from that of a priest. While both provide counseling and visit the sick, a pastor’s week is often heavily dedicated to sermon preparation. This involves deep study of the original biblical languages, theological research, and crafting a message that is both theologically sound and practically relevant. A pastor is also typically the primary administrative leader of a local congregation, overseeing staff, managing church programs, and providing vision for the community’s mission and outreach. In many Protestant denominations, especially Baptist, Pentecostal, and non-denominational churches, the pastor is often married with children, and his family is seen as part of the ministry team. His authority comes less from a sacramental office and more from his demonstrated calling, theological training, and the congregation’s recognition of his gifts for leadership and teaching. The focus is on function and gifting rather than on an indelible sacramental character.

Paths to Ministry: Training and Ordination Compared

The journey to becoming a priest or a pastor is another area where the differences in theology and ecclesiology become strikingly clear. The path to the Catholic priesthood, for instance, is highly standardized and centralized. After a period of discernment, a man enters a seminary, a specialized school for priestly formation. Seminary training typically lasts at least five to seven years and includes intense academic study in philosophy, theology, scripture, and canon law. But it’s not just an academic pursuit; it is a holistic formation that includes spiritual direction, pastoral internships, and community living. A key requirement in the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church is celibacy; candidates for the priesthood make a promise of celibacy for the sake of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Ordination itself is a sacrament. A bishop, who stands in the apostolic succession, ordains the man through the laying on of hands. This ceremony is believed to confer an indelible “sacramental character” on the soul of the new priest, configuring him to Christ the High Priest. This ordination is forever; once a priest, always a priest, even if he is later laicized and cannot function publicly. In the Eastern Orthodox and many Anglican churches, the process is similar, involving lengthy theological education and sacramental ordination by a bishop. While Orthodox and Anglican priests can be married, the marriage must occur before their ordination to the diaconate or priesthood.

The path to becoming a pastor in the Protestant world is far more diverse. There is no single, universal process. In mainline denominations like Lutheranism or Methodism, the process is more formalized, requiring a master’s degree from a seminary (often a Master of Divinity) and ordination by a bishop or a presbytery. However, in many evangelical, Baptist, or non-denominational churches, the process can be much less formal. The primary emphasis is on a person’s internal “call” from God, which is then confirmed by the evidence of their spiritual gifts and their character. A pastor in these settings might have a seminary degree, but they might also be trained through a church’s internal internship program or a Bible college. Ordination is often performed by the local congregation or a council of elders from the local church or denomination, and it is seen as a public recognition and commissioning for ministry rather than the conferral of a sacramental character. This allows for a much wider variety of backgrounds and life situations, including married pastors with families being the norm.

A Day in the Life: Contrasting Daily Responsibilities

Imagine shadowing a Catholic priest and a Protestant pastor for a day. While you would see some overlap—like pastoral counseling or hospital visits—the rhythm and focus of their days would be markedly different. A typical day for a priest often begins early with the celebration of Mass, either a public service or a private one. He will pray the Liturgy of the Hours, the official set of prayers that mark the hours of each day, which is a canonical obligation. His morning might be dedicated to administrative tasks, but his afternoon is likely reserved for hearing confessions. He may also be preparing a homily (a shorter sermon based on the day’s scripture readings), but his primary liturgical preparation is for the Eucharist. His week is structured around the sacramental needs of his parish: scheduled Masses, baptisms, anointing the sick, and preparing couples for marriage. His identity is deeply intertwined with his role as the one who makes the sacraments present for his people.

Now, follow a Protestant pastor. Their day likely starts in their home, with family, before heading to the church office. A significant block of time, often 15-20 hours per week, is dedicated solely to sermon preparation. This involves exegeting biblical texts, reading commentaries, and writing a full-length sermon designed to teach, exhort, and inspire the congregation. Their day is filled with staff meetings, planning for upcoming church events, and leadership development. They might lead a small group Bible study, pre-marital counseling sessions, and make hospital visits. While they certainly pray and study the Bible devotionally, their schedule is not built around a mandatory liturgical prayer cycle like the Liturgy of the Hours. The pastor’s life is a blend of CEO, counselor, and teacher, with the Sunday sermon serving as the weekly deadline around which much of their work revolves.

Symbolism and Attire: What They Wear and Why

The clothing worn by religious leaders is not just a uniform; it’s a powerful symbol of their role, theology, and tradition. In the case of a priest, the most iconic garment is the clerical collar, or “Roman collar.” This white, detachable tab is a public sign of his ordination and commitment. During liturgical services, the priest wears vestments, each with deep symbolic meaning. The alb, a white robe, symbolizes purity and the baptismal garment. The chasuble, the often beautifully decorated outer garment, is worn for Mass and symbolizes the yoke of Christ. The colors of the vestments change with the liturgical seasons—purple for penance, white for feast days, red for martyrs, and green for ordinary time. These vestments connect the priest and the congregation to the ancient, universal practices of the church, emphasizing continuity and the sacredness of the ritual.

For a pastor, attire is generally much less prescribed and often reflects the culture of the denomination and the local congregation. In many traditional Lutheran, Methodist, or Anglican churches, a pastor may wear a clerical collar and a robe with preaching tabs during services, showing a connection to historical Protestantism. However, in a vast number of evangelical, Baptist, and non-denominational churches, the pastor might wear business casual attire or even jeans and a shirt on Sunday morning. This sartorial choice is intentional; it is meant to break down barriers, to seem approachable and “just like everyone else,” reflecting the theology of the priesthood of all believers. The focus is on the message, not the messenger. The lack of formal vestments symbolizes that the pastor is a member of the congregation who has been set apart for a specific function, not a member of a separate sacerdotal class.

Leadership Structure and Church Governance

The question of authority and how a church is governed is another critical point of divergence in the pastor vs priest conversation. Churches with priests typically operate within a hierarchical, episcopal polity. This means authority is structured in a top-down manner. The local priest reports to a bishop, who oversees a diocese (a geographic region). The bishop may, in turn, report to an archbishop or, in the case of the Catholic Church, the Pope in Rome, who is considered the successor of Saint Peter. This structure emphasizes unity, doctrine, and apostolic succession. The priest is assigned to a parish by the bishop; he does not apply for the job or get voted in by the congregation. His authority is derived from his ordination and his place within this apostolic chain of command.

In contrast, churches led by a pastor employ a variety of governance models, most of which involve a much greater degree of local congregational control. A common model is congregational polity, used by Baptists, many non-denominational churches, and others. In this system, the local church is autonomous and self-governing. The congregation itself holds the ultimate authority. They call (hire) their own pastor, approve the budget, and make major decisions. Another model is presbyterian polity, used by Presbyterian churches and some others. Here, authority is vested in a group of elders (“presbyters”) who govern the local church and a regional presbytery. The pastor serves as a teaching elder within this council. In both models, the pastor’s leadership is more collaborative and answerable to a local body, reflecting a decentralized approach to church authority.

Theological Focus: Sacraments vs. The Word

At the heart of the pastor vs priest distinction lies a fundamental difference in theological emphasis. For traditions centered on the priest, the primary focus is on the Sacraments. Catholicism, for instance, holds that there are seven sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Penance (Confession), Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony. These are defined as “efficacious signs of grace, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Church, by which divine life is dispensed to us.” The priest is the essential minister of most of these sacraments. The entire liturgical and spiritual life of the community flows from and leads back to these sacred encounters, especially the Eucharist. The church building itself, often adorned with a tabernacle, is designed to facilitate this sacramental reality.

For Protestant traditions led by a pastor, the primary focus is on the Word of God—the Bible. The Reformation slogan sola scriptura (“Scripture alone”) underscores this. The Bible is the ultimate and sole infallible authority for faith and practice. Therefore, the central task of the pastor is to proclaim and teach that Word. The sermon is the engine of the worship service. While sacraments (or ordinances) are observed—typically Baptism and Communion (the Lord’s Supper)—they are usually understood as symbolic acts of obedience and remembrance rather than as channels of grace that effect what they signify. The church building is often designed as an auditorium or a worship center, focused on facilitating clear hearing and seeing of the preached Word, with a pulpit as its central physical feature.

Can Women Serve as Pastors or Priests?

The role of women in ministry is one of the most visible and debated topics in modern Christianity, and the pastor vs priest divide is starkly evident here. In the Catholic and Orthodox churches, the priesthood is reserved exclusively for men. This teaching is based on the precedent set by Jesus choosing only men as his twelve apostles, and the theological understanding that the priest, acting in persona Christi, must be a male icon of Christ. While women hold many important roles in these traditions, including as religious sisters, theologians, and chancellors, the sacramental priesthood is not open to them.

The landscape is completely different within Protestantism, though it is not uniform. Many mainline Protestant denominations, such as the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, The United Methodist Church, the Presbyterian Church (USA), and the Episcopal Church, fully ordain women as pastors and clergy. They interpret the relevant biblical passages in their historical context and believe the overarching biblical message of equality in Christ supports women in leadership. However, many conservative evangelical, Baptist, and non-denominational churches do not ordain women as senior pastors, based on their interpretation of certain New Testament epistles that they see as prescribing male headship in the church and home. This issue remains a significant point of diversity and discussion within the Protestant world, showing that the title of pastor does not automatically imply a single stance on gender and leadership.

Presbyterian vs Baptist: A Comprehensive Guide to Two Pillars of Protestant Faith

The Personal and Community Relationship

The nature of the relationship between the faith leader and the congregation also differs significantly. A Catholic priest is often addressed as “Father,” a title that reflects his spiritual role as a paternal figure and the provider of sacramental life. There can be a certain respectful distance in this relationship, shaped by the priest’s role as a sacramental mediator and his commitment to celibacy. He is a man set apart, which can foster deep respect but sometimes a degree of formality. The relationship is often centered on his sacramental duties—he is the one who baptizes your children, hears your confession, and anoints your loved ones.

The relationship with a Protestant pastor is often more informal and personal. He is typically addressed as “Pastor [Last Name]” or even just by his first name. Because he is usually a married family man, he is seen as sharing in the same life experiences as his parishioners—raising children, managing a household, dealing with financial pressures. This can make him seem more relatable and approachable for counseling on marriage, parenting, and daily life. The relationship is built less on his sacramental function and more on his teaching, preaching, and personal discipleship. The congregation often sees him as a friend and a mentor who walks alongside them in their faith journey.

A Comparative Table of Pastor vs Priest

| Feature | Priest | Pastor |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Tradition | Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican (High Church) | Protestant (Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran, Non-denominational, etc.) |

| Theological Emphasis | Sacraments, particularly the Eucharist | Preaching and Teaching the Word of God |

| Core Function | Mediator of sacraments, offering sacrifice | Shepherd, teacher, preacher, leader |

| View of Communion | Real Presence of Christ (Transubstantiation) | Varies: Symbolic memorial to Real Presence (in some Lutheran/Anglican) |

| Path to Ministry | Seminary training + Sacramental Ordination by a Bishop | Varies: Seminary to internal church training; Ordination by congregation/denomination |

| Governance | Hierarchical (Episcopal) under Pope/Bishop | Congregational or Presbyterian (Elder-led) |

| Marriage | Celibate (in Roman Catholicism); Married (in Orthodoxy & some Anglicanism if married before ordination) | Typically married; marriage is the norm |

| Common Attire | Clerical collar, liturgical vestments | Varies: Business casual to suit to clerical robe and collar |

| Address | “Father” | “Pastor [Name]” or first name |

| Women in Role | No (in Catholicism & Orthodoxy) | Yes (in many mainline denominations); No (in many conservative churches) |

Quotes on Ministry and Leadership

“The priest is not a priest for himself; he is a priest for you.” — Saint John Vianney

“Preaching is the embodiment of a message in a personality. A sermon is truth mediated through personality.” — Harry Emerson Fosdick

“The task of the pastor is to help the congregation to become a community of people who are learning how to live the story of God.” — Eugene Peterson

“A priest is a man who holds up the Cross before the world, and says to the world: ‘This is the truth! Look at it! See, it is the only thing that can save you!'” — Fulton J. Sheen

Frequently Asked Questions about Pastor vs Priest

What is the main difference between a pastor and a priest?

The main difference lies in their primary function and theological context. A priest is a figure in Catholic, Orthodox, and some Anglican traditions whose central role is to administer the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, which is considered the real presence of Christ. A pastor is a role in Protestant traditions whose central role is to preach the Bible, teach the congregation, and provide spiritual leadership as a shepherd to the flock. The pastor vs priest distinction is rooted in different views on church authority, the means of grace, and the “priesthood of all believers.”

Can a priest become a pastor or vice versa?

This is a complex process. A Catholic priest who leaves the active ministry (is laicized) could potentially become a Protestant pastor if he undergoes the training and ordination process of that denomination. However, he would no longer function as a Catholic priest. The reverse is also possible but would require a Protestant pastor to undergo Catholic seminary formation, receive the sacrament of Holy Orders, and accept Catholic doctrine, including celibacy if he is joining the Latin Rite. Such transitions are significant life changes involving deep theological and personal discernment.

Why do some pastors call themselves priests?

This is most common in certain Anglican, Episcopal, or high-church Lutheran communities. These denominations exist in a kind of middle ground, retaining some of the liturgical and sacramental theology of Catholicism (including the term “priest” for their clergy) while embracing key principles of the Reformation. In these contexts, the term “priest” is used to emphasize their role in celebrating the Eucharist, which they may also believe in the Real Presence of Christ, but it is often coupled with a strong emphasis on preaching, creating a blended identity in the pastor vs priest spectrum.

Do pastors hear confessions like priests?

Generally, no. In Catholic and Orthodox theology, sacramental confession to a priest is the ordinary means for the forgiveness of grave sins after baptism. Most Protestant traditions reject the necessity of confession to a clergy member, believing that individuals can confess directly to God. However, many pastors strongly encourage and provide opportunities for “pastoral counseling” or spiritual direction, where congregants can share their struggles, receive biblical advice, and pray together. This is seen as a form of spiritual care and accountability, not a sacrament.

Is a minister the same as a pastor or a priest?

“Minister” is a broader, more generic term that can refer to any person who leads religious services, whether they are a priest, a pastor, a deacon, or a lay leader. It simply means “servant.” In some Protestant contexts, “minister” is used interchangeably with “pastor.” In a Catholic context, the priest is a type of minister, but the term is not used as his specific title. So, while all pastors and priests are ministers, not all ministers are specifically called pastors or priests.

Conclusion

The journey through the world of pastor vs priest reveals a rich tapestry of Christian faith and practice. These are not just interchangeable job titles but are windows into deep theological worlds. The priest, rooted in ancient, sacramental tradition, serves as a mediator and custodian of the sacred mysteries, guiding his flock through the channels of grace found in the sacraments. The pastor, a product of the Reformation’s emphasis on the priesthood of all believers, serves as a shepherd-teacher, guiding his flock through the exposition of Scripture and personal discipleship. One is not inherently better than the other; they are different expressions of devotion, serving different understandings of how God meets His people.

Ultimately, the pastor vs priest distinction reminds us of the beautiful and sometimes complicated diversity within the global Christian community. Understanding these differences fosters not only intellectual clarity but also a greater respect for the various paths our fellow believers walk. Whether one finds spiritual nourishment in the solemn silence of a Eucharistic liturgy or in the dynamic preaching of a Sunday sermon, the goal is the same: to draw closer to the divine. So, the next time you hear the terms, you’ll see more than just a title; you’ll see a story of history, theology, and a profound commitment to serving God and community.