Welcome to the fascinating and often noisy world of backyard chickens! Whether you’re a seasoned poultry keeper or just starting to dream of fresh eggs each morning, one of the first and most important distinctions to understand is the difference between a rooster and a hen. It might seem straightforward, but telling them apart, especially in younger birds, can be a real head-scratcher. This isn’t just about labeling your flock members; it’s about understanding their unique behaviors, roles, and needs. Knowing the difference between a rooster vs hen is fundamental to managing a happy, healthy, and harmonious coop. This comprehensive guide will dive deep into every aspect, from the obvious physical traits to the subtle nuances of their personalities, helping you become an expert in identifying and appreciating both of these incredible birds.

The Basics: What Defines a Rooster and a Hen?

Before we get into the nitty-gritty details of combs and crowing, let’s start with the fundamental biological definitions. At its core, the difference is one of sex and reproductive function. A hen is a female chicken. Her primary biological role is to lay eggs. While a hen does not need a rooster to produce the eggs we eat for breakfast, she does require one to fertilize those eggs if the goal is to hatch chicks. Hens can be surprisingly complex creatures with distinct personalities, social hierarchies, and maternal instincts.

A rooster, on the other hand, is a male chicken. His biological purpose is to fertilize eggs and protect the flock. Roosters are the guardians, the alarm systems, and the patriarchs of the chicken world. They are equipped with specific physical attributes and hardwired behaviors to fulfill these roles. The dynamic between a rooster vs hen is a classic example of sexual dimorphism in the animal kingdom, where the two sexes of the same species exhibit different characteristics beyond their reproductive organs. Understanding this basic premise is the key to unlocking everything else about their appearance and behavior.

The term “chicken” is the general species name for both, with “rooster” (or cock) and “hen” specifying the gender. Chicks are the young, and until they develop their gender-specific traits, they are often called “pullets” for young females and “cockerels” for young males. The journey from a fluffy chick to a proud rooster or a productive hen is a fascinating process of development where the differences slowly become apparent. This foundational knowledge sets the stage for appreciating the more visible and audible distinctions we will explore next.

The Crow and the Cluck: Vocal and Behavioral Differences

If you’ve ever been woken up at dawn by a loud, echoing call, you’ve experienced the most famous behavioral difference firsthand. Crowing is the signature sound of the rooster. While it’s famously associated with sunrise, a rooster can and will crow at any time of day to announce his presence, assert dominance, warn of danger, or simply because he feels like it. Each rooster has a unique crow, and some breeds are louder and more vocal than others. This vocalization is a powerful tool for establishing territory and keeping the flock alert.

Hens are not silent by any means, but their vocalizations are entirely different. The most common sound is the cluck, a conversational noise used to communicate with other flock members. The famous “buk-buk-buk-bagawk!” sound is the egg song, a hen’s proud announcement after laying an egg, which often encourages other hens to join in a noisy chorus. Hens also use a series of soft clucks to communicate with their chicks, guiding them and warning them of danger. The difference in volume and purpose between the crow and the cluck is one of the easiest ways to distinguish a rooster vs hen from a distance.

Behaviorally, their roles define their actions. A rooster’s day is spent patrolling, watching for predators from hawks to cats, and finding food. He will often perform a behavior called “tidbitting,” where he finds a tasty morsel, calls the hens over with a distinctive sound, and may even pick up and drop the food repeatedly to show them. This is part of his courtship and protective role. Hens, meanwhile, focus on foraging, dust bathing, and, of course, laying eggs. They have a complex social structure known as the “pecking order,” which determines access to food, nesting boxes, and perching spots. While a rooster may be at the top of the overall hierarchy, the hens maintain their own intricate ranking system amongst themselves.

A Matter of Appearance: Physical Differences Between Roosters and Hens

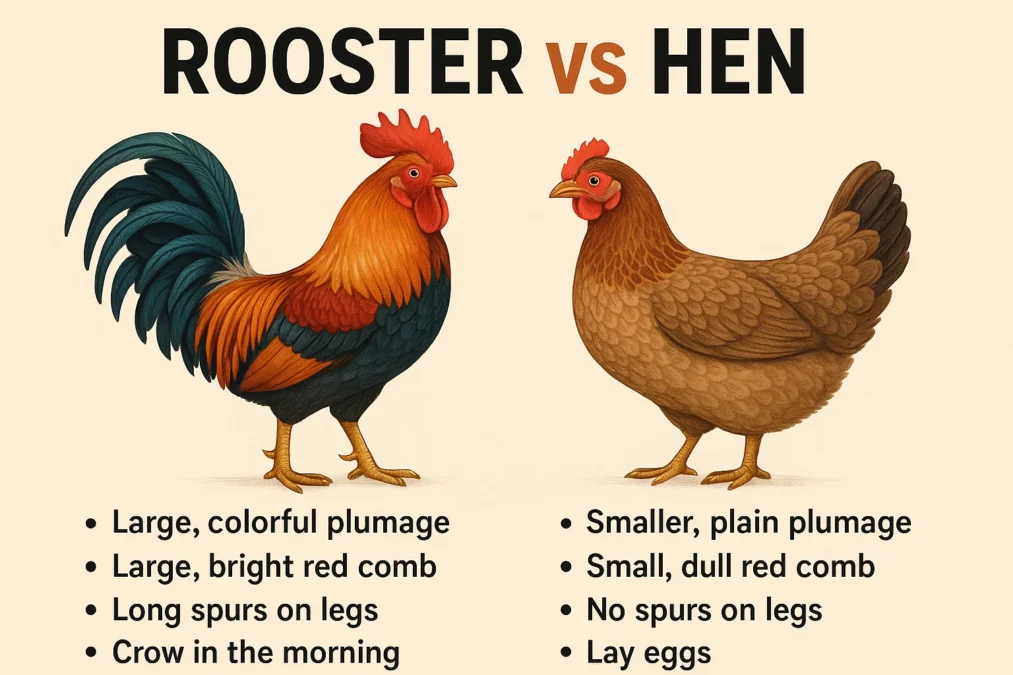

While behavior is a strong indicator, physical traits are the most reliable way to tell a rooster vs hen apart, especially once they reach maturity. Roosters are typically larger and more flamboyant, built to impress mates and intimidate rivals. One of the most noticeable features is their plumage. Roosters often have long, shiny, flowing saddle feathers on their backs near the tail and elaborate, pointed hackle feathers around their neck. Their tail feathers are long, curved, and dramatic, known as sickle feathers. This glamorous appearance is all for show, designed to attract hens.

Hens, in contrast, have more practical and subdued feathers. Their plumage is often duller, providing better camouflage while sitting on a nest. Their hackle and saddle feathers are rounded and less showy, and their tail feathers are short and straightforward. Beyond feathers, look at the head. Roosters usually have larger, more pronounced combs and wattles (the red fleshy parts on top of the head and under the chin). These often turn a brighter red earlier than those on hens. Another key difference is the spur—a bony, sharp protrusion on the back of the leg. Roosters develop large, sharp spurs used for fighting and defense. Hens can have small, rudimentary spurs, but they are rarely prominent.

It’s crucial to remember that breed plays a huge role. Some breeds, like Sebrights or Campines, are “hen-feathered,” meaning the roosters lack the typical pointed plumage and look very similar to hens. In these cases, you must rely on other cues like size, comb development, and behavior. Other breeds, like Silkies, are notoriously difficult to sex, even for experts, until they either crow or lay an egg. For most standard breeds, however, the combination of larger size, showy feathers, big combs, and spurs will reliably identify your rooster.

The Role in the Flock: Protector vs. Producer

The physical and behavioral differences between a rooster vs hen exist for a reason: they have evolved to fulfill complementary but distinct roles within the flock. The rooster is the guardian. His job is perpetual vigilance. He will constantly scan the skies and the surroundings for threats. If he spots danger, he will emit a specific alarm call, sending the hens scattering for cover. A good rooster will often put himself between the threat and his hens, and he will not hesitate to fight a predator to protect his flock. This protective instinct is ingrained and is a valuable asset for any free-ranging flock.

The hen’s primary role is that of the producer. She is the egg-layer, the foundation of the flock’s sustainability. Her body is a marvel of biological engineering, dedicated to creating and laying eggs. Beyond production, a hen with a strong maternal instinct becomes the brooder and mother. When she goes “broody,” she will insist on sitting on a clutch of eggs around the clock, barely eating or drinking, to hatch them and then fiercely protect and raise her chicks. This nurturing role is just as critical to the flock’s survival as the rooster’s protective one.

Together, they create a balanced ecosystem. The rooster provides security, allowing the hens to focus more on foraging and laying. He also maintains order, often breaking up squabbles between hens. The hens, through their egg production, ensure the next generation. It’s a partnership that has worked for thousands of years. In a backyard setting, you can have a flock of only hens quite successfully. However, introducing a rooster changes the dynamic, adding a layer of natural protection and the possibility of fertilized eggs for hatching. Understanding these roles helps you appreciate the value each bird brings to the coop.

Temperament and Personality: What to Expect from Each

When considering a rooster vs hen, their general temperaments follow trends, but individual personality varies wildly by breed and upbringing. Roosters are often portrayed as aggressive, but this is not always the case. A well-bred and well-socialized rooster can be a gentleman—protective yet respectful of his human caretakers. He may follow you around the yard or even eat from your hand. However, some roosters can become territorial and aggressive, especially during the breeding season or if they perceive you as a threat to their hens. This behavior can include charging, flogging (jumping and spurring), and posturing.

Hens generally have more varied and complex personalities within a narrower band of behavior. Some are bold and curious, always the first to investigate something new. Others are skittish and shy. Some are friendly and enjoy human company, while others prefer to keep their distance. You might have a hen that is a relentless bully to others lower in the pecking order and another that is meek and submissive. Their personalities often shine through in their daily interactions around the coop and run. Most hen aggression is directed at other hens within the established social structure.

It’s important to note that breed selection is the biggest determinant of temperament. Some rooster breeds, like Buff Orpingtons, are renowned for their docile and friendly nature. Others, like Malay or Gamefowl breeds, are notoriously fierce. Similarly, hen breeds like Silkies are known for their sweet, docile, and broody nature, while Leghorns are often more flighty and independent. When choosing birds for your backyard, researching breed-specific temperament is just as important as considering egg color or cold hardiness. This ensures a good fit for your family, especially if children are involved.

The Practicalities of Keeping Roosters and Hens

The decision to keep a rooster vs hen (or both) comes with a set of practical considerations that every potential chicken keeper must weigh. The most obvious factor is local ordinances. Many urban and suburban areas have strict regulations against keeping roosters due to their noise (crowing), which can lead to complaints from neighbors and potential legal issues. Always check your local zoning laws before bringing home a cockerel. Hens, while not silent, are usually permitted because their clucking is far less disruptive and carries a shorter distance.

Another major consideration is flock dynamics. A flock of only hens will be quiet and productive but may lack a natural guardian. Introducing a rooster can provide protection but also introduces the potential for aggression. You must also consider the ratio of roosters to hens. A single rooster can comfortably manage and mate with up to ten or twelve hens. Having too many roosters for the number of hens can lead to intense fighting between the males and over-mating of the hens, which can cause feather loss and skin damage on their backs. Managing this ratio is key to a peaceful coop.

From a resource perspective, roosters eat just as much as hens but don’t provide anything in return except fertilization and protection. Hens provide eggs. For those focused on maximum egg production from their feed investment, roosters are an unnecessary expense. However, for those interested in breeding their own chicks, a rooster is, of course, essential. He will also ensure that every egg laid is fertilized, which is only a concern if you are collecting eggs daily for eating (a fertilized egg is indistinguishable from an unfertilized one in taste and nutrition unless it has been incubated under a hen).

The Life Cycle: From Chick to Adult

The journey of determining a rooster vs hen begins on day one, but it’s a process that unfolds over weeks. As chicks, male and female are nearly identical. For most backyard breeders, they are bought as “straight-run” or “as-hatched,” meaning they are unsexed, and you get a random mix. This is a gamble, as you could end up with mostly roosters. “Pullets” are sexed chicks that are guaranteed to be female, though there is a small margin of error. The first clues appear at a few weeks old when cockerels often develop larger combs and wattles and longer legs than their pullet sisters.

As they approach puberty (around 4-5 months), the differences become stark. The cockerels’ combs and wattles will grow larger and turn a vivid red. They will begin to practice crowing, which starts as a funny, squeaky, embarrassing sound often called a “cock-a-doodle-don’t.” Their saddle and hackle feathers will become pointier, and they will start to spar with each other, practicing the fighting moves they might need later. Pullets, meanwhile, will have smaller, paler combs and their feathers will remain more rounded. The ultimate sign of a hen is, of course, the laying of her first egg, usually between 18 and 24 weeks of age.

The adult stage is where the rooster vs hen dichotomy is fully realized. A mature rooster is in his prime, bold and confident in his role. A hen reaches her peak egg-laying potential within her first year. As they age, a rooster may become less aggressive or may slow down, but he can remain fertile for many years. A hen’s egg production will gradually decline each year after the first. Understanding this life cycle helps you anticipate and manage the changes in your flock, from the awkward teenage phase to the dignified retirement years.

Breed Spotlights: How Differences Vary by Breed

The classic image of a rooster vs hen is often based on common breeds like the Leghorn or Rhode Island Red. However, the world of chickens is incredibly diverse, and the distinctions can look very different across various breeds. For example, in the Brahma breed, both roosters and hens are massive, giant birds. The rooster will still have the pointed hackles and larger comb, but the size difference might be less pronounced than in a smaller breed. Their gentle nature also means the behavioral differences are more subdued.

Take the Sebright breed, as mentioned earlier. This is a true “hen-feathered” breed. The roosters are genetically designed to have feathers exactly like the hens—short, rounded, and laced. They lack the long sickle feathers, pointed saddles, and flowing hackles of most roosters. Telling a Sebright rooster from a hen requires looking at other, more subtle signs: the rooster’s comb will be larger and brighter red, he will crow, and he will have a more upright and proud carriage. This breed perfectly illustrates why you can’t rely on feathers alone.

On the other end of the spectrum, gamefowl breeds like the Modern Game or Old English Game show extreme sexual dimorphism. The roosters are lean, muscular, and athletic with an aggressive and alert posture. The hens are much smaller and finer-boned. The difference is immediately obvious. Similarly, in highly ornamental breeds like the Polish, the rooster’s extravagant crest of feathers and large sickle tail make him unmistakable compared to the hen, who has a more modest, though still fancy, crest. Appreciating these breed variations makes the hobby of chicken keeping endlessly interesting.

Common Myths and Misconceptions Debunked

The world of poultry is not immune to myths, and the topic of rooster vs hen has its fair share. One of the most persistent myths is that a hen can spontaneously turn into a rooster. While extremely rare, a phenomenon called spontaneous sex reversal can occur in adult hens whose ovary has been damaged by disease. The hormone-producing adrenal gland can take over, triggering the development of male characteristics like crowing, larger combs, and even spurs. However, this hen-turned-rooster is genetically still female and is sterile, unable to fertilize eggs. It is a fascinating biological anomaly, not a common occurrence.

Another common myth is that you need a rooster for hens to lay eggs. This is completely false. Hens are egg-laying machines that will produce eggs on a regular cycle regardless of whether a rooster is present. The eggs you buy at the supermarket are from hens that have almost certainly never even seen a rooster. A rooster is only needed to fertilize the egg, which is only necessary if you want to hatch chicks. For the average backyard keeper just wanting breakfast eggs, a rooster is optional.

A third misconception is that all roosters are mean. While some individuals can be aggressive, a rooster’s behavior is heavily influenced by his breed, how he was raised, and how he is treated. A rooster that is handled frequently and gently from a young chick is far less likely to see humans as a threat. Furthermore, his aggression is usually a manifestation of his protective instinct. He is not being “mean” for no reason; he is doing the job he was bred to do. Understanding his motivation is the first step in managing and respecting his behavior.

Wolf Spider vs Brown Recluse: The Ultimate Guide to Identification, Bites, and Safety

Making the Choice: Which is Right for Your Flock?

So, after all this, should you choose a rooster vs hen for your backyard? The answer depends entirely on your goals, your environment, and your personal preferences. If you live in a city or a suburb with close neighbors, your choice is likely made for you: hens only. The risk of noise complaints makes keeping a rooster impractical and often illegal in these settings. A flock of hens will provide you with eggs, entertainment, and garden fertilizer without the dawn serenades.

If you live in a rural area with more space and fewer restrictions, the choice becomes yours. A good rooster can be a tremendous asset. He will protect your hens from aerial and ground predators, find food for them, and keep the peace within the flock. He adds a beautiful, majestic presence to the yard and completes the natural social structure of the chickens. If you ever plan to hatch your own chicks, he is indispensable. For many, the classic barnyard experience isn’t complete without a rooster greeting the day.

However, be prepared for the challenges. Even the best rooster can become aggressive during mating season. You must be confident in handling him and teaching any children in the household how to interact with him safely. You also need to ensure you have enough hens for him to avoid over-mating. Ultimately, the decision is a personal one. Many chicken keepers start with hens and later decide to introduce a rooster to their flock once they are more experienced and have the right setup for him.

Comparison Table: Rooster vs Hen at a Glance

| Feature | Rooster (Male) | Hen (Female) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Flock protector, fertilizer | Egg layer, mother |

| Size | Generally larger, more muscular | Generally smaller, more rounded |

| Plumage | Showy, pointed hackle/saddle feathers, long sickle tail feathers | Duller, rounded feathers, short tail |

| Comb & Wattle | Larger, brighter red, develops earlier | Smaller, paler red, develops later |

| Spurs | Large, sharp, and prominent | Small, blunt, or absent |

| Vocalization | Loud crow | Clucks, cackles (egg song) |

| Behavior | Protective, vigilant, may spar | Foraging, nesting, may be broody |

| Egg Laying | Does not lay eggs | Lays eggs (fertile or infertile) |

| Typical Temperament | Can be bold/aggressive; breed-dependent | Can be docile/shy; breed-dependent |

Quotes from the Coop

- “A good rooster is the king of his domain, not a tyrant. He watches the skies so his hens can focus on the earth.” – Anonymous Backyard Chicken Keeper

- “The difference between a rooster and a hen is the difference between a guardian and a creator. One ensures survival today, the other ensures tomorrow.” – Poultry Husbandry Proverb

- “A flock without a rooster is quiet and productive. A flock with a good rooster is whole, protected, and truly alive.” – Modern Homesteading Blog

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell a rooster from a hen when they are chicks?

Sexing chicks is very difficult and is best left to trained professionals. However, some methods include vent sexing (examining the chick’s vent for subtle differences, highly accurate but requires expertise) and feather sexing. For some breeds, you can look at wing feather development at day-old: pullets’ primary feathers will be longer than their coverts, while cockerels’ will be the same length. For most backyard buyers, purchasing “pullets” from a reputable hatchery is the safest bet if you don’t want roosters.

Can a hen crow like a rooster?

Yes, though it is uncommon. Usually, this happens in one of two scenarios. An older, top-ranking hen in a flock with no rooster may sometimes start to crow to assert dominance. More rarely, a hen can experience a spontaneous sex reversal due to an ovarian issue, leading to hormonal changes that trigger male behaviors like crowing and the development of comb and spurs. Genetically, she remains a female.

Are fertilized eggs different to eat?

Not at all. A fertilized egg, if collected daily and refrigerated, is nutritionally and tastistically identical to an unfertilized egg. The tiny white spot on the yolk (the blastodisc) may appear slightly larger and have a bullseye appearance (blastoderm) if fertilized, but this is not visible to the naked eye when cooking. You are only eating an egg, not an embryo. An embryo only begins to develop if the egg is kept warm (around 85-100°F) for more than 24 hours.

Why is my rooster attacking me?

Rooster aggression is almost always rooted in his role as protector. He likely sees you as a threat to his flock or a challenger to his dominance. This can be more common during the breeding season when his hormones are at their peak. To mitigate this, avoid running or turning your back, as this triggers his prey drive. Use a large rake or broom to gently block his advances. Sometimes, carrying a treat bucket and associating yourself with positive things (food) can help change his perception.

How many hens should I have per rooster?

The generally recommended ratio is at least 8 to 10 hens for one rooster. This ensures that no single hen is over-mated, which can lead to feather loss and wounds on her back. If you have more than one rooster, you will need an even larger flock of hens to keep the peace and prevent fighting among the males. A ratio of one rooster to twelve hens is often considered ideal for flock harmony.

Conclusion

Understanding the difference between a rooster vs hen is about so much more than just identifying gender. It’s about appreciating the unique and complementary roles they play in the intricate social world of chickens. From the rooster’s proud crow and vigilant protection to the hen’s quiet clucking and incredible egg-laying ability, each bird brings something vital to the flock. Whether you choose to keep a flock of peaceful hens or introduce a majestic rooster to your coop, this knowledge empowers you to provide the best care, manage their dynamics, and fully enjoy the rewarding experience of backyard poultry keeping. The journey from a curious observer to a knowledgeable chicken keeper starts with this fundamental understanding of the beautiful dichotomy between the rooster and the hen.