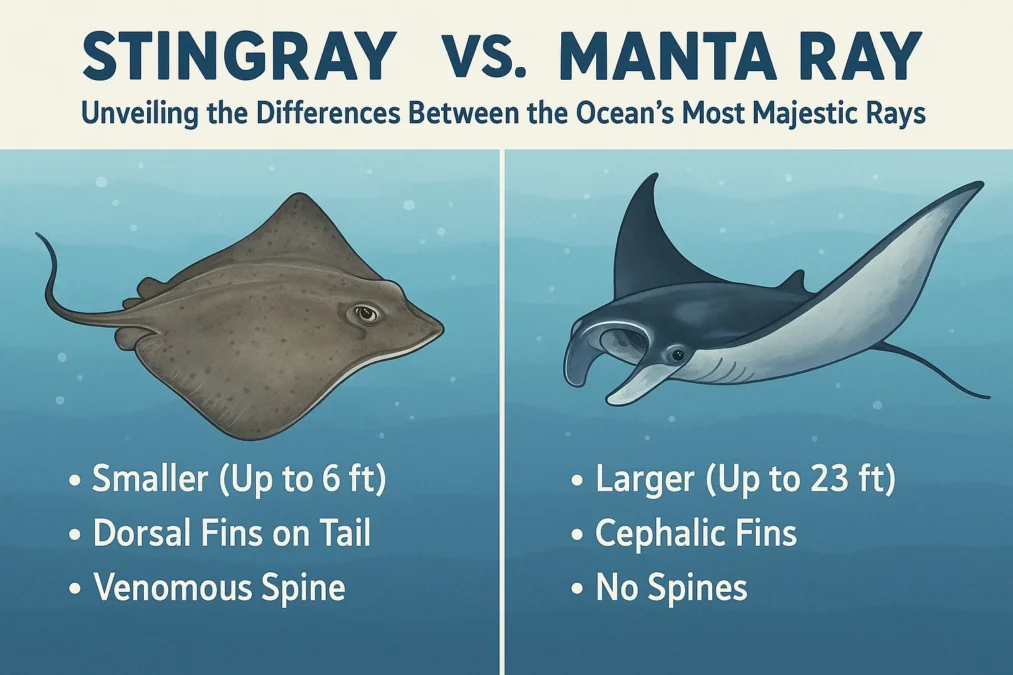

Gliding through the ocean with an almost otherworldly grace, rays are some of the most captivating creatures beneath the waves. Their flattened bodies and wing-like pectoral fins create the illusion of underwater flight, a mesmerizing sight for any diver or snorkeler. But for many, there’s a common point of confusion: what exactly is the difference between a stingray and a manta ray? It’s easy to see why the mix-up happens. They share a similar body plan, both belonging to the same subclass of cartilaginous fish, the Elasmobranchs, which also includes sharks. This family connection means they share traits like skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone. However, to lump them together is to miss a world of fascinating distinction.

The truth is, while they are evolutionary cousins, the stingray and the manta ray are as different as a house cat is from a lion. One is often a bottom-dwelling, cryptic resident of the seafloor, while the other is a pelagic, soaring giant that commands the open water. Understanding the differences between them not only enhances our appreciation for marine biodiversity but also dispels common myths and fears. This deep dive will explore every facet of the stingray vs manta ray debate, from their anatomy and size to their diet, behavior, and their complex relationships with humans. We will journey from sandy shallows to the blue vastness of the open ocean to uncover the unique stories of these two incredible animals. So, let’s settle the stingray vs manta ray question once and for all.

Setting the Stage: A Shared Evolutionary Heritage

Before we delve into their differences, it’s crucial to understand what links these two magnificent creatures. Both stingrays and manta rays are part of the class Chondrichthyes, the cartilaginous fish. This means that, unlike most fish you might think of, their skeletons are not made of hard bone but of flexible cartilage—the same material that gives structure to your nose and ears. This lightweight skeleton is a common trait they share with their more famous relatives, the sharks. Furthermore, they both possess five to seven pairs of gill slits on the underside of their bodies for breathing, and many species give birth to live young, a phenomenon known as ovoviviparity.

The most striking shared feature, and the one that causes the most confusion, is their body shape. Both have evolved incredibly enlarged pectoral fins that are fused to their heads, creating a distinctive disc-like or diamond-shaped body. This design is a masterpiece of evolutionary engineering, perfect for their aquatic environment. They propel themselves not with a tail fin like a typical fish, but by undulating or flapping these large, wing-like fins, creating a beautiful, fluid motion that looks like flying through water. This efficient mode of locomotion allows for great maneuverability and energy conservation. However, this is where the broad similarities end. When you look closer, the adaptations that have evolved on this shared blueprint tell two very different stories of survival and ecological niche.

To use an analogy, think of a single blueprint used to build two different vehicles. One builder uses it to create a rugged, stealthy all-terrain vehicle designed for navigating complex landscapes and staying hidden—this is the stingray. Another builder uses the same basic blueprint to construct a massive, graceful, and powerful glider designed for efficient, long-distance travel through open skies—this is the manta ray. The core structure is related, but the purpose, design, and capabilities are worlds apart. The following sections will unpack these specialized adaptations, starting with the most obvious and dramatic difference: their sheer size.

The Titans and the Ground Dwellers: A Matter of Size and Shape

The most immediate and jaw-dropping difference in the stingray vs manta ray comparison is their size. Manta rays are giants of the ray world. In fact, they are the largest rays in the ocean. The giant oceanic manta ray (Mobula birostris) can achieve a truly staggering wingspan, reaching up to 29 feet or more—wider than a large school bus is long. Even the smaller reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi) boasts an impressive wingspan of up to 18 feet. Encounters with these behemoths are often described as transcendent experiences, as their immense, dark shadows glide overhead, blocking out the sun.

Stingrays, on the other hand, are generally much more modest in size. While there is a huge diversity of species, most of the stingrays people commonly encounter have a wingspan ranging from a few inches to a few feet. The familiar southern stingray, often seen in Caribbean sand flats, might reach a wingspan of about 5 feet. There are exceptions, of course, like the colossal freshwater stingray of Southeast Asia, which can weigh over 1,300 pounds and measure over 6 feet across, but these are the outliers. For the most part, the stingray vs manta ray size debate is a contest between a compact sedan and a jumbo jet.

Beyond sheer scale, their body shapes offer clear clues. Manta rays have a distinctly triangular shape, with wide, pointed pectoral fins that form a broad, powerful diamond. Their heads are broad and flat, with a characteristic pair of cephalic fins—the horn-like structures that roll up when swimming and unfurl to help funnel water and food into their massive mouths. Stingrays typically have a more rounded, oval, or diamond-shaped disc, but without the prominent triangular “wings.” Their bodies are designed for life on or near the seabed, often being flatter and more streamlined to hug the contours of the ocean floor, a stark contrast to the manta’s build for open-water cruising.

The Face Tells the Tale: Head Structure and Feeding

If you’re still unsure how to tell a stingray vs a manta ray, just look at their faces. This is where their evolutionary paths have diverged most dramatically, driven entirely by how they eat. A manta ray’s head is unlike any other fish. It is characterized by two prominent cephalic fins, which unfurl from the sides of its head. These are not menacing horns but highly specialized tools. When feeding, the manta ray will unroll these cephalic fins to help channel a constant stream of plankton-rich water into its wide, gaping mouth, which is positioned right at the front of its head.

This mouth is enormous, but it is entirely toothless. The manta ray is a filter feeder, one of the largest in the ocean. It swims with its mouth wide open, passively consuming vast quantities of microscopic zooplankton, tiny fish eggs, and small crustaceans. The water passes over rows of red, feathery gill plates—specialized structures that filter out the tiny food particles, which are then swallowed. This elegant, energy-efficient system allows the manta ray to sustain its immense body on some of the smallest life forms in the sea. Watching a manta ray perform barrel rolls through a dense patch of plankton is a breathtaking spectacle of nature’s precision.

Now, look at a stingray. Its mouth is located on the underside of its body, perfectly positioned for its life as a bottom feeder. You will not see cephalic fins on a stingray. Instead of filter feeding, stingrays are active hunters of benthic, or seafloor, organisms. Their diet consists of creatures like clams, crabs, shrimp, worms, and small fish. To find this prey, which is often buried in the sand, stingrays possess an incredible superpower: electroreception. Special organs called the ampullae of Lorenzini can detect the tiny electrical fields produced by the muscle contractions of hidden prey.

Once a stingray has located its dinner, it uses its powerful, crushing jaw plates to crack open shells and exoskeletons with ease. It doesn’t need sharp teeth for biting, but rather robust, pavement-like dental plates to pulverize its tough-food prey. This fundamental difference in feeding strategy—the manta ray’s graceful, open-water filter feeding vs the stingray’s stealthy, electro-sensitive hunting on the seafloor—is the core of the stingray vs manta ray distinction and dictates almost every other aspect of their biology and behavior.

The Tail: A Story of Defense and Function

The tail is perhaps the most infamous feature in the stingray vs manta ray discussion, and for good reason. It is the source of both the stingray’s name and its fearsome reputation. Most stingray species possess a long, whip-like tail that is equipped with one or more venomous, serrated barbs. This barb is a formidable defensive weapon, not an offensive one. Stingrays are not aggressive creatures; they are shy and reclusive. The barb is used purely in self-defense when they feel threatened, cornered, or accidentally stepped on.

The structure of the stingray’s barb is a marvel of biological weaponry. It is sharp, serrated like a steak knife, and connected to venom glands. The serrations make it difficult and painful to remove, and the venom causes intense, immediate pain, swelling, and potential tissue damage in humans. While a sting is rarely fatal, it is a potent reminder to respect these animals and practice the “stingray shuffle”—dragging your feet through the sand rather than taking steps—to warn them of your approach and avoid an accidental encounter.

In the starkest contrast, the manta ray has no barb on its tail whatsoever. Its tail is long, slender, and whip-like, but it is entirely harmless. The manta ray has no venom, no sting, and no defensive spike. This is a crucial point of differentiation. When people ask about the stingray vs manta ray, the presence or absence of a stinger is the single most important safety distinction. Without a barb, the manta ray relies on its immense size, speed, and agility to evade predators like large sharks and orcas. Its tail serves no defensive purpose and is largely vestigial, a remnant of its evolutionary past. The manta ray is a gentle giant, physically incapable of stinging anyone.

Masters of Their Domains: Habitat and Behavior

The lives of stingrays and manta rays unfold in very different worlds, a direct result of their feeding strategies and physiology. Stingrays are the masters of the benthic zone. They are predominantly bottom-dwellers, found in a huge range of coastal marine environments, from tropical coral reefs and seagrass beds to temperate bays and even deep-sea floors. Many species, like the aptly named round stingray, spend much of their time partially buried in the sand or sediment. This cryptic behavior serves two purposes: it hides them from potential predators and allows them to ambush their prey.

Their connection to the seafloor is integral to their existence. Some stingray species, like the blue-spotted stingray, are more active swimmers and can be seen flitting over reefs, but they rarely venture far from the complex structure of the bottom. Freshwater stingrays have even colonized river systems in South America and Asia, demonstrating their adaptability to various bottom-dwelling environments. Their social behavior is generally solitary or occurs in loose aggregations, often driven by mating or abundant food sources.

Manta rays, conversely, are pelagic nomads. They are creatures of the open ocean, though they are frequently seen visiting specific “cleaning stations” on coral reefs. A cleaning station is a specific location on the reef where smaller fish, like wrasses and cleaner shrimp, remove parasites from the manta’s skin and gills. This symbiotic relationship is vital for the manta’s health and provides a reliable opportunity for humans to observe them. Their behavior is not tied to the seafloor but to the currents and plankton blooms that dictate their food supply.

They are highly migratory, traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles across ocean basins. Furthermore, manta rays exhibit complex social behaviors that are far more advanced than those of stingrays. They are known to gather in large groups for feeding, mating, and cleaning. Research has even suggested they may have a degree of self-awareness; they are one of the few fish species to pass the mirror test, indicating a potential capacity for recognizing their own reflection. This pelagic, social lifestyle of the manta ray stands in sharp contrast to the generally solitary, bottom-focused life of the stingray.

German Roaches vs American Roaches: The Ultimate Homeowner’s Guide to Identification and Elimination

Intelligence and Social Structures: The Brainy Giant and the Solitary Hunter

The discussion of behavior naturally leads to an exploration of intelligence, and here the stingray vs manta ray comparison reveals another surprising difference. Manta rays possess the largest brain-to-body ratio of any fish. Their brains are large and complex, with expanded areas for learning, problem-solving, and social interaction. Scientists believe this advanced cognitive capacity is linked to their migratory, social lifestyle and their need to navigate vast, featureless ocean environments, remember productive feeding grounds, and coordinate with other mantas.

This intelligence is observable. Mantas at cleaning stations appear to actively solicit cleaning from specific fish species. They have been documented performing seemingly playful behaviors, like somersaulting and interacting with bubbles from divers. Their sophisticated social structures involve learning from one another, a trait once thought to be the domain of mammals and birds. The giant oceanic manta ray, in particular, is known for its deep dives and long migrations, behaviors that likely require complex neural mapping and memory.

Stingrays are certainly not unintelligent. Their well-developed electroreceptive system is a testament to a highly specialized form of sensory intelligence perfectly suited to their environment. They can learn to associate specific locations or stimuli with food, as any diver who has been on a controlled stingray-feeding tour can attest. However, their cognitive world appears to be more directly tied to immediate survival—finding food, avoiding predators, and reproducing—without the evidence of the complex social learning and potential self-awareness seen in manta rays. Their intelligence is that of a sophisticated hunter, while the manta ray’s intelligence seems to approach that of a social, curious explorer.

Human Interactions: From Fear to Fascination

The relationship between humans and rays is a tale of two extremes, perfectly encapsulating the stingray vs manta ray dynamic in the human psyche. Stingrays have long been feared, largely due to the notoriety of the barb. The tragic death of wildlife expert Steve Irwin in 2006 cemented this fear in the public consciousness, though it’s crucial to understand that such events are extraordinarily rare. Stingrays do not attack; they defend. Most human injuries occur when a person accidentally steps on a camouflaged ray in shallow water, prompting a reflexive defensive strike with the tail.

Despite this fear, stingrays are also a source of fascination and ecotourism. Places like “Stingray City” in the Cayman Islands allow people to safely interact with and feed southern stingrays, fostering appreciation and dispelling myths. On a less positive note, some stingray species are threatened by habitat loss and are caught as bycatch in fisheries. Their tough skin, known as shagreen, was once used for sword grips and other items, though this practice has declined.

Manta rays, lacking a stinger and possessing a serene, majestic demeanor, have almost universally been viewed with awe and reverence. They are the stars of the dive tourism industry, generating millions of dollars annually for local economies as people flock to destinations like Indonesia, the Maldives, and Mexico for a chance to swim with them. This “charismatic megafauna” status has helped fuel global conservation efforts. However, manta rays face severe threats from targeted fisheries, primarily driven by the demand for their gill plates for use in pseudo-traditional Chinese medicine, a market that has pushed their populations into decline. The story of human interaction is thus one of misunderstood danger for the stingray and adored vulnerability for the manta ray.

Conservation Status: Threats Beneath the Waves

Both stingrays and manta rays face significant anthropogenic threats, though the nature and intensity of these threats can differ. For manta rays, the primary driver of population decline has been direct, targeted fishing. Their gill plates are falsely believed to have medicinal properties, leading to a lucrative and devastating trade. Their large size, slow growth, and very low reproductive rates—a female may give birth to only one pup every two to five years—make them exceptionally vulnerable to overfishing. As a result, both species of manta ray are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

International protection has been crucial. They are listed on Appendix II of CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), which regulates their international trade. Many countries have also established marine protected areas that safeguard key manta ray habitats and cleaning stations. The future of manta rays hinges on continued enforcement of these protections and the reduction of consumer demand for their body parts.

The conservation picture for stingrays is more complex due to the vast number of species. Many common stingray species are still considered of “Least Concern,” but numerous others are threatened. The primary dangers for stingrays are habitat degradation—such as the destruction of seagrass beds and coral reefs—and bycatch. Because they live on the seafloor, they are highly susceptible to being caught in bottom trawls, gillnets, and fish traps intended for other species. The massive freshwater stingrays of Southeast Asia are critically endangered due to habitat loss from dam construction, pollution, and fishing. The conservation challenge for stingrays is their sheer diversity and the fact that they often lack the “charismatic” appeal that drives conservation funding for species like manta rays.

Cultural and Ecological Significance

Throughout history, both stingrays and manta rays have captured the human imagination and played vital roles in their ecosystems. In many Polynesian and Melanesian cultures, the manta ray is a sacred animal, often seen as a guardian spirit or a symbol of grace and power. Their images are carved into canoes and tattoos, representing a deep connection to the ocean. Stingrays, with their cryptic and sometimes dangerous nature, often feature in folklore as tricksters or powerful, sometimes feared, entities.

Ecologically, both are indispensable. Manta rays, as large filter feeders, act as ocean connectors. They consume plankton in surface waters and, through their nutrient-rich excretions, help fertilize different parts of the ocean, including nutrient-poor coral reef ecosystems. They are a vital part of the marine food web, and their movements help cycle nutrients across vast distances. Stingrays play the role of the benthic ecosystem engineer. By foraging in the sediment, they stir up the sand, aerating it and releasing nutrients trapped within. This bioturbation is crucial for the health of seafloor communities.

Their feeding habits also help control populations of burrowing invertebrates, preventing any one species from dominating the ecosystem. The removal of either stingrays or manta rays from their respective environments would have cascading negative effects, disrupting the delicate balance of marine life. They are not just inhabitants of the ocean; they are active participants in shaping and maintaining the health of their worlds, from the sandy bottom to the open blue.

A Side-by-Side Comparison

To crystallize all the information, here is a detailed comparison table highlighting the key differences in the stingray vs manta ray debate.

| Feature | Stingray | Manta Ray |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Generally small to medium (inches to ~6-7 feet across, with exceptions). | Very large to gigantic (10 to 29+ feet across). |

| Body Shape | Rounded, oval, or diamond-shaped disc. | Distinctly triangular with pointed “wings.” |

| Head | No cephalic fins. Mouth on the underside. | Prominent, rolled cephalic fins. Mouth at the front. |

| Tail | Long, whip-like, usually with one or more venomous barbs. | Long, whip-like, but completely harmless and without a barb. |

| Diet | Carnivorous bottom feeders (clams, crabs, worms). | Filter feeders (zooplankton, tiny crustaceans). |

| Habitat | Primarily benthic (seafloor), in coastal waters, reefs, and some freshwater. | Primarily pelagic (open ocean), visiting cleaning stations on reefs. |

| Social Behavior | Mostly solitary or in loose aggregations. | Often social, forming large groups for feeding and mating. |

| Defense Mechanism | Venomous tail barb for defense. | Size, speed, and agility to escape predators. |

| Reproduction | Ovoviviparous (live young). | Ovoviviparous, usually one pup per litter after long gestation. |

| Interaction with Humans | Often feared due to sting; some ecotourism. | Revered and sought after for dive tourism; threatened by fishing. |

| Conservation Status | Varies by species (Least Concern to Critically Endangered). | Both species listed as Vulnerable globally. |

Voices from the Deep

The awe these creatures inspire is best captured in the words of those who study and admire them.

Dr. Andrea Marshall, ‘Queen of Mantas’ and Co-Founder of the Marine Megafauna Foundation: “Manta rays are the gentle giants of the sea. They are intelligent, curious, and each one has a unique personality. Swimming with them is like encountering an alien intelligence, one that is peaceful and profoundly beautiful.”

Unnamed Marine Biologist specializing in Elasmobranchs: “The fear surrounding stingrays is largely misplaced. They are shy, elegant creatures that want nothing to do with us. Understanding their behavior is the key to coexisting safely. The ‘stingray shuffle’ isn’t just a silly dance; it’s a conversation with the ocean floor, telling its residents you mean no harm.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Do manta rays have stingers?

No, manta rays are completely harmless and do not possess a stinger or barb of any kind. This is one of the most important distinctions in the stingray vs manta ray discussion. Their tails are smooth and whip-like, serving no defensive purpose. The confusion often arises because they are both rays, but the manta ray evolved without this defensive weapon, relying instead on its large size and speed to avoid predators.

What is the main difference between a stingray and a manta ray?

While there are many differences, the most fundamental one lies in their feeding ecology and the resulting anatomy. The stingray is a bottom-dwelling carnivore with a mouth on its underside, hunting for shellfish and worms. The manta ray is a giant, open-ocean filter feeder with a front-facing mouth, consuming microscopic plankton. This core difference dictates their size, shape, habitat, tail structure, and behavior, making the stingray vs manta ray comparison a study of two very different evolutionary solutions for survival in the ocean.

Can a stingray sting kill you?

While extremely painful, a stingray sting is very rarely fatal. The venom is designed to cause intense local pain and tissue damage, not to kill large animals like humans. Fatalities are exceedingly rare and are usually the result of a highly unusual circumstance, such as the barb piercing a vital organ, which is what occurred in the tragic case of Steve Irwin. For the vast majority of people, a sting results in a painful wound that requires medical attention to manage pain, clean the wound, and ensure the barb fragment is removed, but it is not life-threatening.

Are manta rays related to sharks?

Yes, both manta rays and stingrays are closely related to sharks. They all belong to the same subclass of fish, the Elasmobranchii. This group is defined by having skeletons made of cartilage, five to seven gill slits on the sides of their heads (though in rays, they are on the underside), and dermal denticles (tooth-like scales) covering their skin. So, when you look at a ray, you are essentially looking at a flattened shark that has evolved a completely different body plan and lifestyle over millions of years.

How can I tell them apart when I’m snorkeling or diving?

The easiest way to tell a stingray vs a manta ray is by observing their location and behavior. If you see a ray resting on or flying just above the sandy seafloor, often partially buried, it is almost certainly a stingray. It will have a rounded shape and you likely won’t see its mouth. If you see a massive, triangular ray effortlessly “flying” through the open water, far above the reef or sand, and it has two distinct “horns” (cephalic fins) on its head, you are in the presence of a majestic manta ray. The context is your best clue.

Conclusion

The journey through the world of stingray vs manta ray reveals a story of incredible diversification from a common ancestor. They are a powerful example of how evolution can take a basic body plan and sculpt it into two masterpieces of adaptation, each perfectly suited to its own niche. The stingray is the stealthy, specialized hunter of the seafloor, a creature of quiet mystery equipped with a powerful defense. The manta ray is the soaring, gentle giant of the open ocean, a filter-feeding marvel that captivates with its size, intelligence, and grace.

Understanding the differences between them—the presence of a barb, the location of the mouth, the habitat they call home—enriches our experiences in the ocean and replaces fear with knowledge and respect. Both of these remarkable animals face an uncertain future due to human activities, from habitat destruction to targeted fishing. By appreciating their unique roles in the marine ecosystem and supporting conservation efforts, we can help ensure that future generations will also have the privilege of witnessing a stingray materialize from the sand or the awe-inspiring sight of a manta ray gliding silently into the blue. The stingray vs manta ray is not a competition, but a celebration of the beautiful diversity of life beneath the waves.