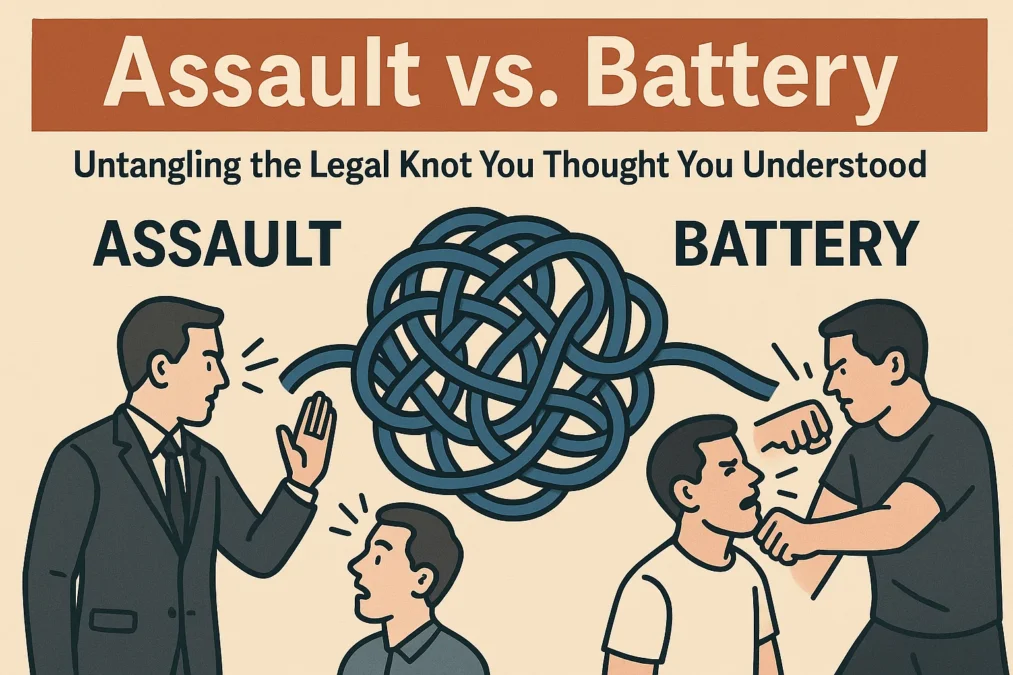

You’ve probably heard the terms tossed around together so often they’ve practically merged into a single concept: “assault and battery.” In everyday conversation, we use them interchangeably to describe a physical fight. You might say someone “assaulted” another when they threw a punch, or refer to a barroom brawl as a case of “battery.” But in the eyes of the law, these are two distinct crimes with separate elements, definitions, and implications. Understanding the difference between assault vs battery isn’t just a matter of legal pedantry; it’s crucial for anyone involved in a personal injury case, a criminal matter, or even just for being an informed citizen.

This confusion is understandable. The legal system itself often groups them together, and the specifics can vary from state to state. However, at their core, the concepts of assault and battery are built on a fundamental distinction: one is about the fear of harm, and the other is about the actual harm. Unraveling this knot is the key to grasping how the law protects our personal safety and bodily integrity. This article will serve as your comprehensive guide, diving deep into the historical roots, legal definitions, real-world examples, and modern applications of these two separate but related offenses. We will explore the nuances of assault vs battery to give you a clear, confident understanding of where the law draws the line.

The Foundation of Personal Safety in Law

To truly appreciate the assault vs battery distinction, we need to take a quick trip back in time. Our modern legal concepts didn’t appear out of thin air; they evolved from English common law, a system built on precedent and tradition. In this old system, assault and battery were developed as separate “torts” (civil wrongs) and separate crimes. The division was logical and addressed different kinds of violations. Battery was actually the older, more straightforward offense. It concerned itself with any unauthorized, harmful, or offensive touching of another person. The focus was on the integrity of the physical body—the idea that your person is inviolable.

Assault, on the other hand, was a more sophisticated legal creation. It was designed to protect not the body itself, but the mind. The law recognized that causing someone to fear imminent bodily harm was, in itself, a wrong that deserved a remedy. This was a profound development. It meant that you didn’t have to wait until you were actually struck to have a legal claim; the act of creating a reasonable apprehension of harm was actionable. This historical separation established the bedrock upon which all modern assault vs battery discussions are built. The two were never meant to be the same thing, and this foundational difference continues to shape court rulings and legal arguments to this day, influencing everything from self-defense claims to the awarding of damages in civil lawsuits.

This common law heritage was imported to the United States and forms the backbone of our criminal and tort law. While state legislatures have since codified and sometimes altered these definitions, the core principles remain. Some states keep the crimes completely separate, with separate statutes and penalties. Others have merged them into a single statutory crime, often labeled “assault and battery,” but even then, the prosecution must often prove the distinct elements of each. Understanding this historical context is like having a map before you start a journey; it helps you understand why the legal landscape of assault vs battery is shaped the way it is and prevents you from getting lost in the technicalities.

Defining Assault: The Threat of Harm

So, let’s get down to specifics. What, exactly, is assault in a legal sense? The most important thing to remember is that assault does not require any physical contact. Zero. If you walk away from this article remembering one thing, it should be that assault is the crime of almost being hit. It’s the terrifying moment before a potential impact. Legally, assault is generally defined as an intentional act that causes another person to fear an imminent battery, meaning they have a reasonable apprehension of harmful or offensive contact.

Let’s break down the key elements required to prove an assault. First, there must be an intentional act. This means a voluntary, deliberate movement. Reaching back to throw a punch, lunging at someone with a weapon, or even spitting in their direction can qualify. An accidental movement, like slipping and flailing your arms, typically does not meet the bar for assault. Second, the act must cause a reasonable apprehension of imminent harmful or offensive contact. The key word here is “reasonable.” Would a reasonable person in the same situation have feared they were about to be harmed? This is an objective standard. If the victim is unusually timid or the threat is clearly a joke that any reasonable person would understand, it may not qualify as assault.

The “imminence” requirement is also crucial. The threatened harm must be about to happen—not in the distant future. Saying, “I’m going to find you and beat you up next week,” is a threat, and it may be illegal in other ways, but it does not constitute the specific crime of assault because the harm is not imminent. However, if someone balls up their fist, gets in your face, and says, “I’m going to beat you up right now,” that easily satisfies the imminence requirement for assault. The victim is put in a state of immediate and justified fear, and that is the very injury that the law of assault seeks to address and punish.

Real-World Examples of Assault

To solidify our understanding of assault, let’s paint a few pictures with real-world scenarios. Imagine a crowded subway car. One passenger, angered by a perceived slight, stands up, leans over another passenger, and shakes a clenched fist mere inches from their face, yelling, “You’re about to get hurt!” The fist never makes contact. This is a classic assault. The intentional act (leaning in and shaking a fist) created a reasonable apprehension of imminent harmful contact in the seated passenger. The seated passenger experienced genuine fear, and any reasonable person in that situation would have felt the same.

Consider another common situation: a road rage incident. A driver cuts another driver off. The offended driver pulls up next to the first car at a red light, rolls down their window, and makes a slashing motion across their own throat while staring menacingly. No one has been touched. No property has been damaged. Yet, this is very likely assault. The threatening gesture is an intentional act that communicates a clear and immediate threat of violence, creating a reasonable fear in the other driver. The law steps in at this moment of threat, not waiting for the physical violence to begin.

Even in a bar, the distinction is clear. If one patron aggressively pokes a finger into another patron’s chest during an argument, that physical contact likely constitutes a battery (which we’ll discuss next). But if that same patron instead pulls his hand back to throw a punch and is stopped by a bouncer before the punch lands, that is assault. The victim saw the punch being telegraphed and feared the imminent impact. In all these examples of assault, the psychological harm, the invasion of personal security, and the creation of fear are the central injuries. The law recognizes that this fear is a real damage, worthy of legal recourse, entirely separate from any physical injury that might follow in a battery.

Defining Battery: The Unwanted Contact

Now, let’s turn our attention to battery. If assault is the threat, battery is the follow-through. It is the actual, physical execution of the harmful or offensive contact that was threatened in an assault. The legal definition of battery is an intentional, unwanted, harmful, or offensive touching of another person. The contact does not have to cause severe injury or even pain. The violation is in the unwanted nature of the touching itself, an infringement on your right to bodily autonomy.

The elements required to prove a battery are distinct from those for assault. First, there must be a volitional act—just like with assault, it must be intentional, not accidental. Second, the act must result in a harmful or offensive touching of the victim. “Harmful” is straightforward; it causes injury, pain, or impairment. “Offensive” is broader; it refers to contact that would offend a reasonable person’s sense of dignity. Spitting on someone, for example, may not cause physical harm, but it is universally considered a profoundly offensive and degrading act, making it a clear battery.

A critical point in the assault vs battery comparison is that battery does not require intent to cause a specific injury, only the intent to make the contact. If you shove someone, intending just to push them out of your way, but they fall and break their wrist, you can be held liable for the battery and all its resulting injuries. Furthermore, the contact can be indirect. If you throw a rock that hits someone, that’s battery. If you set a trap that causes someone to fall, that can also be battery. The touching does not have to be directly from your body to theirs; it just has to be the direct result of your voluntary action.

Real-World Examples of Battery

To see battery in action, let’s return to our earlier scenarios. Remember the road rage incident where the driver made a threatening gesture? That was assault. Now, imagine if, instead of just making a gesture, the enraged driver got out of their car, walked over, and punched the other driver through the open window. The moment the punch lands, the crime of battery has occurred. The intentional act resulted in a harmful and offensive touching. The assault was the threatening approach; the battery was the physical punch.

In a medical context, battery has a very important application. When a doctor performs a surgery or a procedure without a patient’s consent, it can constitute battery. Your consent to touch is a fundamental defense against a battery claim. If you consent to an operation on your left knee and the surgeon, without your knowledge or consent, operates on your right knee instead, that is an unauthorized touching—a battery. The surgeon may have had the best intentions, but the law protects your right to control what happens to your own body.

Even in seemingly minor altercations, battery can occur. Imagine someone at a party snatches a hat off another person’s head. There is no pain, no physical injury. But this is still likely a battery. The act of snatching the hat involves an offensive contact with the person (as the hat is considered an extension of the person). It is an unwanted touching that violates a reasonable person’s sense of dignity and personal space. This example perfectly illustrates that the core of battery is not the severity of the harm, but the lack of consent for the contact. It reinforces the principle that every individual has the right to be free from any intentional, unauthorized physical interference.

The Crucial Intersection: How Assault and Battery Work Together

While we’ve been carefully pulling apart the concepts of assault vs battery, it’s now time to see how they frequently intertwine. In many real-life situations, assault and battery are two parts of a single, violent sequence. The assault is the lead-up, the moment of threat and fear. The battery is the culmination, the moment of physical impact. Understanding this relationship is key to seeing the full picture of a violent encounter from a legal perspective.

Consider a classic scenario: someone draws back their fist (the assault), and then they proceed to punch you in the face (the battery). In this case, the assault is often considered a “lesser included offense” of the battery. This means that by proving the battery occurred, the prosecution has automatically proven that an assault occurred as well, as you cannot have a battery without first having the imminent apprehension that defines assault. The victim first feared the punch (assault), and then experienced the punch (battery). This is why you will often see a single criminal charge of “assault and battery”—it describes this common, linked sequence of events.

However, it is absolutely vital to remember that they can and do occur independently. You can have an assault without a battery. Our earlier example of the subway passenger who was threatened with a fist but not hit is a perfect illustration. The crime was complete the moment the fear was instilled. Conversely, you can have a battery without an assault. How? If you are struck from behind without any warning, you never saw it coming. There was no moment of apprehension, no fear of imminent harm. The first you knew of the attack was the physical impact itself. In this case, there was a battery (the unwanted contact) but no assault (because there was no prior apprehension). This is a less common but legally significant scenario that highlights the independence of these two legal concepts.

Emigrate vs Immigrate: The Ultimate Guide to Getting These Tricky Words Right

Assault vs Battery in the Criminal and Civil Courts

One of the most important practical distinctions in the assault vs battery discussion lies in the two different arenas where these cases are played out: criminal court and civil court. The same incident can give rise to both a criminal case and a civil lawsuit, but the purposes, procedures, and potential outcomes are vastly different. Understanding this dual nature is critical for anyone navigating the legal consequences of a violent altercation.

In a criminal case, assault and battery are considered offenses against the state or society as a whole. The government, represented by a prosecutor, brings the case against the defendant. The goal is not to compensate the victim but to punish the wrongdoer and uphold public order. The burden of proof is very high: “beyond a reasonable doubt.” If convicted, the defendant faces penalties like jail time, probation, fines paid to the state, and a criminal record. The victim’s role in a criminal trial is primarily as a witness for the prosecution. The outcome is about justice and punishment for breaking society’s rules.

In a civil case, assault and battery are personal wrongs, or torts. The victim (the plaintiff) brings the lawsuit directly against the perpetrator (the defendant). The goal is not to punish the defendant with jail time, but to compensate the plaintiff for the harms and losses they suffered. This is about making the victim whole again, at least in a financial sense. The burden of proof is lower: “by a preponderance of the evidence,” meaning it’s more likely than not that the defendant is liable. If the plaintiff wins, the defendant is typically ordered to pay monetary damages, which can cover medical bills, therapy for emotional distress, lost wages, pain and suffering, and sometimes punitive damages meant to punish particularly egregious conduct.

Aggravated Assault and Aggravated Battery

When people discuss serious violent crimes, they often hear the terms “aggravated assault” and “aggravated battery.” These are not separate crimes from assault and battery; rather, they are enhanced versions that carry much more severe penalties. The “aggravation” comes from the presence of certain factors that make the crime more heinous in the eyes of the law. Understanding what elevates a simple assault or battery to an aggravated one is crucial to understanding the full spectrum of these offenses.

Aggravated assault typically involves an assault that is committed with a deadly weapon or with the intent to commit a serious felony, such as rape or robbery. The “deadly weapon” can be anything used in a way that is likely to cause death or great bodily harm—a gun, a knife, a baseball bat, a car, or even a large rock. The mere presence of the weapon during the assault escalates the charge. For example, pointing a loaded gun at someone is almost always classified as aggravated assault, not simple assault, because of the inherent deadly threat. The use of a weapon transforms the nature of the threat, making it far more terrifying and dangerous.

Similarly, aggravated battery is a battery that causes serious bodily injury or is committed with a deadly weapon. “Serious bodily injury” is a legal term that generally means an injury that creates a substantial risk of death, causes permanent disfigurement, or results in the prolonged impairment of a body part or organ. So, while a simple slap might be a battery, a beating that puts someone in the hospital with broken bones and internal bleeding would be aggravated battery. Using a weapon to commit the battery, such as striking someone with a pipe or stabbing them, also elevates it to an aggravated charge. These aggravated offenses are almost always felonies, whereas simple assault and battery can often be misdemeanors.

Defenses to Assault and Battery Charges

Just because someone is accused of assault or battery does not mean they will automatically be found liable or guilty. The law recognizes several valid defenses that can justify or excuse the actions. A successful defense can result in a complete dismissal of the charges or a finding of “not guilty.” Understanding these defenses is a critical part of the assault vs battery landscape, as they provide the accused with a means to argue their side of the story.

One of the most common and widely understood defenses is self-defense. A person is generally justified in using reasonable force to protect themselves from an imminent threat of unlawful force. If someone throws a punch at you (an assault and attempted battery), and you punch back to stop the attack, you can likely claim self-defense. The key is that the force used in response must be proportional to the threat. You cannot respond to a shove with a deadly weapon and claim self-defense. Similarly, defense of others is a valid defense—using force to protect a third party from an imminent assault or battery.

Another key defense is consent. In certain contexts, consent is a complete bar to a battery claim. The most obvious example is contact sports. When you step onto a football field or a boxing ring, you consent to a certain level of physical contact that would otherwise be considered a battery. However, consent is limited to the normal scope of the activity; a hockey player consents to being checked into the boards but does not consent to being slashed in the face with a stick. Other potential defenses include defense of property (though this is often very limited), accident (negating the “intent” element), and privilege (such as a police officer using reasonable force to make a lawful arrest).

The Lasting Impact: Consequences and Ramifications

The repercussions of a conviction or a finding of liability for assault or battery can be severe and long-lasting, extending far beyond the courtroom. A finding of guilt or liability is not just a momentary event; it can cast a long shadow over a person’s life, affecting their freedom, their finances, and their future. It’s important to view these legal concepts not as abstract definitions, but as events with real human consequences.

For the perpetrator, a criminal conviction can mean jail or prison time, hefty fines, mandatory anger management classes, and a permanent criminal record. This record can be a significant barrier to finding employment, securing housing, obtaining professional licenses, and even maintaining child custody rights. In civil court, a judgment for assault or battery can lead to a massive financial burden, including compensation for the victim’s medical bills, lost income, and pain and suffering. If the court awards punitive damages, the financial penalty can be crippling.

For the victim, the impact is often profound and multifaceted. Beyond the immediate physical injuries, victims of battery may suffer from long-term disabilities, chronic pain, and significant medical expenses. Perhaps just as damaging are the psychological effects. Victims of both assault and battery often experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and a pervasive sense of fear and vulnerability. The emotional trauma of being threatened or violated can shatter a person’s sense of safety in the world. The legal process of assault vs battery is society’s mechanism for acknowledging this harm, providing a path to compensation for the victim, and imposing consequences on the wrongdoer.

Modern Applications and Evolving Definitions

The legal concepts of assault and battery are not frozen in time; they continue to evolve to address new societal challenges and technological realities. As our understanding of harm deepens and new forms of interaction emerge, the law must adapt. This evolution ensures that the principles behind assault and battery remain relevant and effective in protecting individuals in the modern world.

One significant area of evolution is in the recognition of emotional and psychological harm. While the fear in a traditional assault has always been psychological, courts and legislatures are increasingly acknowledging the severe impact of threats and harassment that occur outside of a face-to-face confrontation. For instance, persistent cyberstalking and online threats can now form the basis for criminal charges or a civil lawsuit, even if the perpetrator is hundreds of miles away. The legal system is grappling with how to apply the “imminence” requirement of assault to digital threats, but the core idea—protecting people from the fear of harm—remains the same.

Another evolving area concerns the “offensive contact” element of battery. There is a growing legal awareness and sensitivity around violations of bodily autonomy that may not involve direct physical force. For example, in the context of the #MeToo movement, unwanted sexual touching that was once dismissed as “horseplay” or “not a big deal” is now rightfully being recognized as a serious battery. The law is being applied more consistently to affirm that any intentional, unauthorized touching that offends a person’s dignity is a violation, regardless of the perpetrator’s power or status. This reflects a societal shift towards taking all violations of personal integrity seriously, ensuring that the definitions of assault and battery continue to serve their fundamental purpose: to protect every person’s right to live free from fear and physical violation.

Comparison Table: Assault vs Battery at a Glance

| Feature | Assault | Battery |

|---|---|---|

| Core Element | The apprehension or fear of imminent harmful or offensive contact. | The actual physical harmful or offensive contact. |

| Physical Contact Required? | No. It is a crime of threat and intention. | Yes. Unwanted touching is a required element. |

| “Harm” Defined | Psychological harm; the invasion of mental peace and security. | Physical harm or offensive contact to a person’s body or extensions of it (e.g., clothing). |

| Typical Action | Threatening gestures, raising a fist, pointing a weapon, lunging. | Punching, slapping, kicking, spitting, unwanted sexual touching. |

| Key Legal Question | Did the defendant’s act create a reasonable apprehension of imminent harm in the victim? | Did the defendant intentionally cause harmful or offensive contact with the victim? |

| Can They Occur Alone? | Yes. An assault can occur without a battery (a threatened punch that never lands). | Yes. A battery can occur without an assault (being struck from behind without warning). |

Expert Insights on the Distinction

“The simplest way I explain assault vs battery to my clients is this: Assault is the ‘I’m going to hit you.’ Battery is the ‘I just hit you.’ One is the terrifying promise, the other is the painful fulfillment. This distinction is the first thing we establish in any case involving allegations of personal violence.” — Sarah Jenkins, Criminal Defense Attorney

“In medical law, the concept of battery is a cornerstone of patient rights. It’s not about malice; it’s about autonomy. A surgery performed without informed consent is a battery, a technical violation of the patient’s body. This legal principle forces the medical community to respect patient choice above all else, which is the very essence of ethical care.” — Dr. Evan Miles, Bioethicist and Professor of Law

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main difference between assault and battery?

The main difference in the assault vs battery distinction is that assault is the act of creating a reasonable apprehension of imminent harmful or offensive contact, meaning the victim fears they are about to be hurt. It’s a crime of threat. Battery, on the other hand, is the actual, intentional, and unwanted physical contact itself. You can think of it as assault being the swing of a fist, and battery being the punch landing.

Can you be charged with assault if you didn’t touch anyone?

Absolutely. This is a very common point of confusion. Since assault is defined by the threat and the fear it creates, physical contact is not required. If you intentionally act in a way that makes a reasonable person fear they are about to be physically harmed—like raising a weapon or pretending to throw a punch—you can be charged with and convicted of assault even if you never lay a finger on the victim.

Is spitting on someone considered assault or battery?

Spitting on someone is considered battery. While it may be preceded by an assault (the threatening motion of leaning in to spit), the act of spitting itself constitutes an offensive, unwanted physical contact. Because it is a direct, intentional, and deeply disrespectful touching with bodily fluids, it meets all the legal criteria for battery. The victim does not need to prove physical injury, only that the contact was offensive.

How do words alone factor into an assault charge?

Words alone are generally not enough to constitute an assault. There must be some overt action that accompanies the words to create a reasonable apprehension of imminent harm. For example, shouting “I hate you!” from across a parking lot is likely not an assault. However, shouting “I’m going to stab you!” while advancing quickly with a knife in hand certainly is. The action (advancing with the weapon) combined with the words creates the imminent threat required for assault.

What should I do if I am a victim of assault or battery?

Your first priority should always be your safety. Remove yourself from the situation and get to a safe location. Then, contact the police immediately to file a report. Seek medical attention for any physical injuries, even if they seem minor, as this documents the harm. It is also crucial to document everything: take photos of injuries, write down exactly what happened while it’s fresh in your memory, and get contact information for any witnesses. Finally, consider consulting with a personal injury attorney to understand your options for civil recovery, and a victim’s advocate to help you navigate the criminal process.

Conclusion

The journey through the legal landscape of assault vs battery reveals a system designed with nuance and purpose. These are not interchangeable terms, but two distinct legal concepts that protect different, yet equally important, aspects of our personal security. Assault safeguards our mental peace from the terror of imminent harm, while Battery protects our physical bodies from unauthorized violation. From the historical foundations of common law to their modern applications in both criminal and civil courts, the clear demarcation between a threat and its execution remains paramount.

Understanding this distinction—that one is about the fear of contact and the other is about the contact itself—empowers you as a citizen, a potential juror, or someone who may unfortunately find themselves involved in such a case. It allows for clearer communication with legal professionals and a more informed view of news stories and public discourse about violence. Whether you are considering the aggravated versions of these crimes, the potential defenses, or their long-lasting consequences, the central assault vs battery framework provides the clarity needed to navigate this complex area of law. Knowledge of this fundamental legal principle is a powerful tool for protecting your rights and understanding your responsibilities.