There you are, standing in your kitchen, ready to conquer a new recipe. The counter is dusted with flour, the butter is softened, and your whisk is at the ready. You scan the ingredient list: flour, check; sugar, check; eggs, check. Then you see it. The recipe calls for both baking soda and baking powder. A wave of confusion washes over you. Aren’t they basically the same thing? Can you just use one instead of the other? If you’ve ever asked these questions, you are not alone. The confusion between baking soda vs baking powder has puzzled home bakers for generations, leading to flat cookies, dense cakes, and a whole lot of kitchen frustration.

But here’s the good news: understanding the difference isn’t just for professional pastry chefs. It’s the secret key that unlocks the door to consistently fantastic baking. Once you grasp the simple science behind these two powerful white powders, you’ll move from blindly following recipes to truly understanding them. You’ll be able to diagnose why your last loaf of banana bread didn’t rise, predict how a recipe will turn out just by looking at the ingredients, and even make smart substitutions in a pinch. This comprehensive guide will dive deep into the world of baking soda vs baking powder, transforming you from a confused cook into a confident baker. We’ll explore everything from their chemical makeup and how they create lift to when you absolutely need one over the other and how to troubleshoot common baking blunders. So, preheat your oven and get ready—we’re about to clear up the confusion for good.

The Fundamental Science of Leavening

Before we can understand the difference between baking soda and baking powder, we need to talk about what they actually do. Both are known as chemical leavening agents. In simple terms, leavening is what makes your baked goods rise. It’s the process of introducing gas into a dough or batter, creating thousands of tiny air bubbles that expand in the heat of the oven. This network of bubbles gives your cakes, muffins, and cookies their light, airy, and tender texture. Without leavening, we’d be eating dense, hard, and flat discs that would be a sad imitation of the treats we know and love.

Leavening can happen in a few different ways. Yeast is a biological leavener; it’s a living organism that feeds on sugars and produces carbon dioxide gas over a long, slow fermentation. Steam is another powerful leavening agent, especially in pastries like puff pastry or popovers where the high water content rapidly turns to vapor, pushing the layers apart. But for quick breads, cakes, and cookies that need to rise quickly without a long waiting period, we turn to chemical leaveners. This is where our two stars, baking soda and baking powder, take center stage. They are designed to produce a rapid reaction, generating the necessary carbon dioxide quickly and efficiently to give your batters the lift they need before the structure sets in the oven. The entire debate of baking soda vs baking powder boils down to how and when this gas-producing reaction is triggered.

What is Baking Soda?

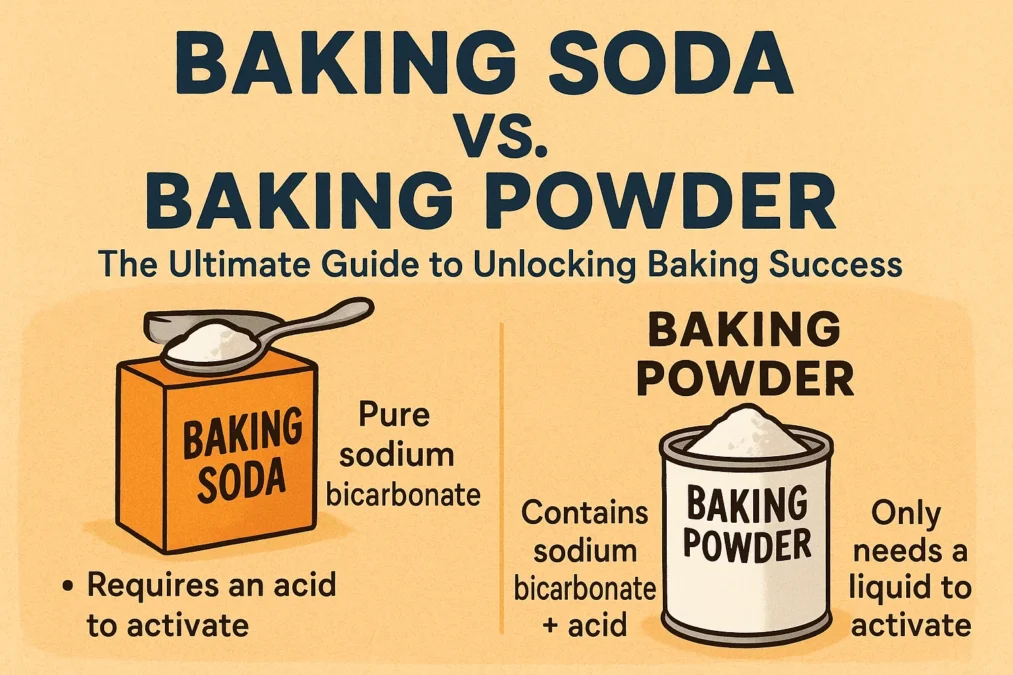

Let’s start with the simpler of the two: baking soda. If you look at its container, you’ll see its scientific name is sodium bicarbonate. At its core, baking soda is a pure chemical compound, a base that remains inert and stable until it comes into contact with an acid. On its own, it doesn’t do anything exciting. But introduce it to an acidic ingredient, and a party starts. This reaction is immediate and vigorous, producing lots of carbon dioxide (CO2) bubbles. You’ve likely witnessed this reaction yourself if you’ve ever made a DIY volcano for a science fair by combining vinegar (an acid) and baking soda (a base).

In the world of baking, this reaction is everything. When you mix baking soda with an acidic ingredient like buttermilk, yogurt, lemon juice, vinegar, brown sugar, honey, or even natural cocoa powder, the same fizzing reaction occurs. This release of CO2 gas, when trapped within the web of gluten and starch in a batter, causes it to inflate and rise. Because the reaction begins the moment the wet and dry ingredients meet, batters made with baking soda must be placed in the oven without delay. Letting the batter sit on the counter for too long will allow the bubbles to escape, resulting in a baked good that falls flat. The primary role of baking soda is to provide a significant and immediate lift, but it also has a crucial impact on color and texture, which we will explore later.

What is Baking Powder?

Now, if baking soda is the pure, single-acting agent, think of baking powder as its more sophisticated, self-contained cousin. Baking powder was invented to solve a specific problem: what if your recipe doesn’t contain an acidic ingredient? If you used pure baking soda in a batter made with regular milk and granulated sugar (which are not acidic), no reaction would occur, and you’d end up with a dense, sunken cake that tastes faintly of soap. To circumvent this, baking powder was created. It is essentially baking soda pre-packaged with its own dry acid (usually cream of tartar) and a buffer, like cornstarch, to keep the two from reacting prematurely.

This clever formulation leads to the key concept of single-acting vs. double-acting baking powder. Most baking powder available in supermarkets today is double-acting. The “double-acting” nature is what makes the discussion of baking soda vs baking powder so important. The first reaction happens when the baking powder gets wet. As soon as you add liquid to your batter, the baking soda and the acid in the powder begin to react, producing some gas. This gives the batter an initial lift during the mixing stage. The second, more important reaction happens with heat. As the batter heats up in the oven, a second acid in the powder (one that is heat-activated) reacts with the remaining baking soda, producing another burst of gas. This second rise provides additional leavening power right when the batter is setting its structure, making it more reliable and forgiving than single-acting powders or baking soda alone.

The Core Difference: A Head-to-Head Comparison

So, let’s get to the heart of the matter. What is the fundamental difference in the battle of baking soda vs baking powder? It all comes down to one word: acid. Baking soda requires an acidic ingredient in the recipe to create a reaction and produce carbon dioxide. It is a single component that needs a partner to work. Baking powder, on the other hand, contains its own acid. It is a complete leavening system in a can. This single distinction dictates everything about how they are used in recipes.

This difference in composition directly affects their potency. Because baking soda is pure sodium bicarbonate, it is about three to four times stronger than baking powder in its leavening power. A little bit of baking soda goes a very long way. This is why you’ll often see recipes call for just a quarter or half a teaspoon of baking soda, while a recipe might call for a full teaspoon or more of baking powder. Using the same amount of baking soda in a recipe that calls for baking powder would be a disaster, leading to an overwhelming soapy flavor and a crumb that’s full of large, tunnel-like holes before likely collapsing. Understanding this potency is critical when you’re evaluating a recipe or considering a substitution in the baking soda vs baking powder dilemma.

A Simple Comparison Table

| Feature | Baking Soda | Baking Powder |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | 100% Sodium Bicarbonate | Baking Soda + Dry Acid(s) + Cornstarch |

| How It Reacts | Requires an Acid + Liquid | Reacts with Liquid & Heat (Double-Acting) |

| Leavening Strength | Strong (3-4x stronger) | Milder |

| When to Use | In recipes with acidic ingredients | In recipes with little or no acid |

| Flavor Impact | Can be soapy/bitter if not neutralized | Generally neutral |

| Common In | Buttermilk pancakes, banana bread, cookies | Biscuits, cakes, muffins |

When to Use Baking Soda

Choosing between baking soda vs baking powder often starts with a careful look at your recipe’s ingredient list. You should reach for baking soda when your recipe includes a significant acidic component. The acid is necessary to trigger the leavening reaction, but it also serves another purpose: it neutralizes the soda. This neutralization is crucial for flavor. Unreacted baking soda leaves a distinct, unpleasant metallic or soapy taste in your baked goods. When properly balanced with an acid, it not only provides lift but also eliminates that off-flavor.

Common acidic ingredients that pair with baking soda include cultured dairy products like buttermilk, yogurt, and sour cream; natural cocoa powder (not Dutch-processed); citrus juices like lemon or lime; vinegar; molasses; and brown sugar (which contains molasses). You’ll often find baking soda in recipes for tangy buttermilk pancakes, classic chocolate cakes made with natural cocoa, deeply flavored gingerbread cookies that rely on molasses, and moist banana bread where the ripe fruit provides some acidity. Baking soda also has a neat trick up its sleeve beyond leavening: it promotes browning. This is why cookie recipes that use baking soda often yield a darker, crisper cookie with a more spread-out shape. It’s not just a leavener; it’s a flavor and color enhancer.

Cortado vs Latte: The Ultimate Guide to Choosing Your Perfect Milk-Based Coffee

When to Use Baking Powder

Baking powder is your go-to leavening agent when a recipe is neutral or alkaline—meaning it contains little to no acidic ingredients. Think of a basic vanilla cake, fluffy biscuits, or simple muffins made with regular milk and granulated sugar. In these scenarios, baking soda would have nothing to react with, leaving its flavor unneutralized and providing no lift. Baking powder, with its built-in acid, is perfectly designed for these situations. It provides a reliable, controlled rise without the need for the baker to worry about acid balance.

Because of its double-acting nature, baking powder is also the champion of batters that need to withstand a little waiting. For example, if you’re making waffles and need to let the batter rest for 15 minutes, or if you’re making multiple batches of muffins, a batter leavened with only baking soda would lose its oomph quickly. The initial reaction would happen during mixing, and the gas would dissipate before hitting the waffle iron or oven. With double-acting baking powder, the heat-activated reaction ensures a second burst of leavening power right when it counts, leading to a lighter, more consistent texture. This makes recipes with baking powder generally more forgiving for beginner bakers navigating the world of baking soda vs baking powder.

Why Recipes Call for Both Baking Soda and Baking Powder

This is the question that often causes the most confusion. If baking powder is already a complete system, and baking soda needs an acid, why would a recipe use both? It seems redundant, but it’s actually a mark of a well-designed recipe. There are two primary reasons for this power-pairing, and both relate to achieving the perfect balance of flavor, texture, and lift.

The first reason is to manage acidity and flavor. Imagine a recipe for the ultimate buttermilk pancakes. It uses a full cup of buttermilk, which is highly acidic. If the recipe used only baking soda to neutralize all that acid, it would require a relatively large amount. While this would neutralize the flavor, it would also create an enormous amount of gas very quickly. The batter might rise too much and then collapse, or it could create an overly porous, crumbly texture. By using a combination, the baking soda neutralizes a portion of the buttermilk’s tang, improving the flavor, while the baking powder provides the additional, steady lift needed for a fluffy pancake without the risk of collapse. The result is a pancake with a balanced, pleasant flavor and a light, tender crumb.

The second reason is all about texture and browning. Baking soda’s alkalinity not only neutralizes acid but also weakens gluten. Weaker gluten means a more tender baked good. Furthermore, as mentioned, baking soda encourages beautiful, deep golden-brown color. So, a recipe might include a small amount of baking soda alongside baking powder not for its primary leavening power, but to tenderize the crumb and enhance browning, while relying on the baking powder for the bulk of the rise. This one-two punch is common in chocolate chip cookies, where you want a bit of spread, a tender center, and a golden-brown color.

The Substitution Conundrum: Can You Swap Them?

In a perfect world, you’d always have the exact ingredient a recipe calls for. But we’ve all been there—mid-recipe, you discover you’re out of one or the other. So, can you substitute one for the other in the baking soda vs baking powder dilemma? The short answer is that it’s tricky and often not ideal, but there are emergency workarounds if you understand the science. The key is to remember that baking soda is much stronger and requires an acid.

If a recipe calls for baking soda and you only have baking powder, you need to account for the difference in strength. Since baking powder is weaker, you’ll need to use a lot more of it to achieve the same amount of lift. A general rule of thumb is to use about three times the amount of baking powder as you would baking soda. For example, if a recipe calls for 1 teaspoon of baking soda, you would use 3 teaspoons (1 tablespoon) of baking powder. However, there’s a major caveat: this will introduce a lot of additional salt and acid into your recipe, which can sometimes affect the taste and texture, potentially making it slightly bitter or altering the browning.

Conversely, if a recipe calls for baking powder and you only have baking soda, the challenge is greater. You cannot use baking soda alone because there’s no acid for it to react with. Your baked good will not rise and will taste terrible. To create a DIY baking powder substitute, you need to combine baking soda with a dry acid. The most common method is to mix 1 part baking soda with 2 parts cream of tartar. So, for 1 teaspoon of baking powder, you would use 1/4 teaspoon of baking soda mixed with 1/2 teaspoon of cream of tartar. This mixture must be used immediately, as it will start to react once it’s mixed and exposed to any ambient humidity. These substitutions are emergency fixes; for consistent results, using the correct leavener as written in the recipe is always the best policy.

Testing for Freshness: Don’t Get Caught with a Dud

Both baking soda and baking powder have a limited shelf life. While baking soda is relatively stable when kept dry and cool, it can eventually lose its potency and can also absorb odors from your pantry, which can affect the flavor of your baked goods. Baking powder, however, is more prone to losing its leavening power over time, especially if the container is frequently opened and exposed to humid air. Using a dead leavener is one of the most common reasons for baking failures, so knowing how to test them is an essential baker’s skill.

Testing baking soda is simple. Take a small bowl and pour about 3 tablespoons of white vinegar into it. Sprinkle about 1/4 teaspoon of baking soda over the vinegar. If it immediately fizzes and bubbles vigorously, it’s still fresh and active. If you get just a few lazy bubbles, it’s time to replace the box. Testing baking powder is a similar process. Put 1/2 cup of hot water from the tap into a small bowl and stir in 1 teaspoon of baking powder. Again, you should see an immediate and enthusiastic fizzing reaction. A weak or non-existent reaction means the baking powder has gone dormant and will not give your cakes and muffins the lift they deserve. It’s a good practice to mark the purchase date on your containers and test them every six months or so, especially if you don’t bake very often.

Common Baking Problems and How to Fix Them

Understanding the principles of baking soda vs baking powder turns you into a baking detective. When something goes wrong, you can often trace the problem back to an issue with your leavening agents. A flat, dense cake or muffin is the most common complaint. This can be caused by using old, inactive baking powder or soda, but it can also happen if you used baking soda in a recipe that didn’t have enough acid to activate it. The result is a heavy, soapy-tasting brick. Similarly, if you over-mix a batter after adding the leaveners, you can burst the delicate gas bubbles that were forming, deflating the batter before it even hits the oven.

On the flip side, sometimes baked goods rise too much and then collapse in the center. This can be a sign of too much leavening. An excess of baking soda or baking powder creates such a violent and rapid production of gas that the structure of the cake (the gluten and starch) can’t stretch to contain it. The bubbles grow too large, merge, and then pop, causing the center to fall as it cools. Another tell-tale sign of too much baking soda is a distinct soapy or bitter aftertaste and a yellowish-green tint inside your baked good, as the unreacted soda alters the color of the cocoa or other ingredients. Paying close attention to these clues—texture, shape, color, and flavor—will help you diagnose and correct your leavening mishaps for next time.

Expert Insight

As renowned food scientist and author Harold McGee writes in On Food and Cooking, “The choice between baking soda and baking powder is determined by the other ingredients in the recipe… The cook’s challenge is to balance the ingredients and the mixing so that the bubbles are formed and then trapped just before and during baking.” This perfectly encapsulates the delicate dance of chemistry and timing that is at the heart of using these ingredients correctly.

Storing Your Leavening Agents for Maximum Potency

To ensure your baking soda and baking powder are ready for action when you are, proper storage is key. Both should be kept in a cool, dry place. A cupboard away from the stove or dishwasher is ideal. Heat and moisture are the enemies of chemical leaveners, as they can trigger the reaction prematurely inside the container, rendering the product useless before you’ve even scooped it. Always make sure the lids are sealed tightly after each use to prevent humidity from getting in.

While many people store their baking supplies in the refrigerator, this is generally not recommended for leavening agents. The constant cooling and warming when taking them in and out of the fridge can cause condensation to form inside the container, which can degrade the product faster. The pantry is the best home for them. A good practice is to write the date of purchase on the box with a permanent marker. While baking powder typically has a shelf life of 6 to 12 months once opened, and baking soda can last longer, their potency will slowly fade. If you can’t remember when you bought it, just perform the simple freshness test described earlier. It takes only seconds and can save you from a baking disappointment.

Beyond Baking: Other Uses for These Kitchen Powerhouses

While our focus has been squarely on the battle of baking soda vs baking powder in the baking arena, it’s worth noting that these humble powders have lives outside the oven, especially baking soda. Its chemical properties make it an incredibly versatile household product. A box of baking soda in your fridge or freezer acts as a powerful odor neutralizer, absorbing funky smells. A paste made from baking soda and water can help soothe insect bites or mild sunburn. Mixed with vinegar, it’s a classic, non-toxic solution for cleaning drains and de-gunking surfaces.

Baking powder, being a mixture that includes baking soda, can also be used for some cleaning tasks, but it is not as pure or effective as baking soda alone for most non-culinary purposes. Its primary mission is in the kitchen, creating light and fluffy baked goods. Baking soda, however, is the true multi-tasker. From polishing silver to scrubbing pots and pans, its mild abrasiveness and reactivity make it a staple for natural cleaning. So, even if you have a box that’s a little past its prime for baking, don’t throw it out—re-purpose it for your household chores!

Conclusion

The journey through the world of baking soda vs baking powder reveals that they are not interchangeable ingredients, but rather specialized tools for a baker’s toolkit. Baking soda is a powerful, fast-acting base that requires an acidic partner to create lift, while also enhancing browning and tenderizing. Baking powder is a convenient, all-in-one leavening system that provides a reliable, double-acting rise, making it perfect for neutral batters and more forgiving for bakers. The true mark of baking mastery comes from understanding why a recipe calls for one, the other, or both. This knowledge empowers you to bake with confidence, troubleshoot problems effectively, and appreciate the beautiful chemistry that happens in your oven. So the next time you see both on an ingredient list, you’ll smile, knowing the baker has carefully balanced the formula for the perfect rise, flavor, and texture. Happy baking!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between baking soda and baking powder?

The core difference lies in their composition and how they react. Baking soda is pure sodium bicarbonate, a base that requires an acidic ingredient (like buttermilk or vinegar) in the recipe to produce carbon dioxide gas and cause rising. Baking powder is a complete leavening system containing both baking soda and a dry acid (and often cornstarch). It only needs a liquid and heat to activate, making it self-contained.

Can I use baking powder if I don’t have baking soda?

You can attempt a substitution, but it’s not a direct 1:1 swap. Because baking soda is about three to four times stronger than baking powder, you would need to use a much larger amount of baking powder. For 1 teaspoon of baking soda, you would use about 3 teaspoons (1 tablespoon) of baking powder. Be aware that this may add a slightly bitter taste due to the extra acid and starch in the baking powder.

What happens if I use baking soda instead of baking powder?

If you use baking soda in a recipe that calls for baking powder, your baked good will likely not rise and will have a strong, unpleasant metallic or soapy flavor. This is because baking powder contains its own acid, while baking soda does not. Without an acidic ingredient to react with, the baking soda remains unneutralized in the batter, leading to the bad taste and no leavening action.

Why do some recipes use both baking soda and baking powder?

Recipes use both to achieve a balance of flavor, lift, and texture. The baking soda is often there to neutralize a prominent acidic ingredient (like buttermilk or cocoa), which improves the flavor. However, using too much baking soda for leavening alone could cause the batter to rise too rapidly and collapse. The baking powder is then added to provide additional, more stable lift. Baking soda also promotes browning and tenderizes the crumb.

How can I test if my baking soda or baking powder is still good?

To test baking soda, put a few tablespoons of vinegar in a bowl and sprinkle 1/4 teaspoon of baking soda on top. It should fizz vigorously. To test baking powder, put 1/2 cup of hot water in a bowl and mix in 1 teaspoon of baking powder. It should also produce an immediate and strong fizzing reaction. If the reactions are weak or non-existent, it’s time to replace them.