Imagine your mind is a house. A single, devastating event, like a tornado, can rip through it. The damage is severe and immediate: shattered windows, a torn-off roof, the foundations shaken. This is often what Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is like—a response to a distinct, terrifying event. Now, imagine a different scenario. Instead of one tornado, your house exists in a climate of perpetual, slow-drip decay. There’s persistent dampness that warps the wood, a faulty electrical system that constantly flickers, and a foundation that’s been slowly eroding for years. The house is still standing, but it’s structurally compromised in ways that are complex, interconnected, and harder to pinpoint. This is the essence of Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD).

For decades, the term PTSD has been the primary lens through which we understand trauma. It’s a vital and validated diagnosis, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. Many people who have endured prolonged, repeated trauma—such as long-term childhood abuse, domestic violence, or being a prisoner of war—find that the classic PTSD symptoms only scratch the surface of their suffering. Their experience often includes a fractured sense of self, profound difficulties in relationships, and a deep-seated feeling of being fundamentally broken. This is the territory of CPTSD. Understanding the distinction between CPTSD vs PTSD is not just an academic exercise; it’s a crucial step toward validation, accurate diagnosis, and effective healing for millions. This article will serve as your deep dive into these two conditions, unraveling their complexities, highlighting their critical differences, and lighting a path toward understanding and recovery.

What is PTSD? The Aftermath of a Single Storm

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is a psychiatric condition that can develop in anyone who has experienced or witnessed a traumatic event. The key here is the nature of the trigger: it’s typically a single, life-threatening, or severely terrifying incident, or a short series of such events. The diagnostic criteria for PTSD are well-established and cluster into distinct categories. Think of it as the mind’s alarm system getting stuck in the “on” position long after the immediate danger has passed. The brain, in its effort to protect you, becomes hyper-vigilant, constantly scanning for threats and reacting to reminders with overwhelming intensity.

To be diagnosed with PTSD, a person must experience symptoms from four main clusters for at least one month, and these symptoms must cause significant distress or impairment in their social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. The first cluster is Re-experiencing, where the trauma intrudes upon the present. This can take the form of vivid, distressing nightmares, flashbacks that make the person feel as if they are reliving the event, or relentless, intrusive thoughts about what happened. The second cluster is Avoidance, where the individual consciously or unconsciously steers clear of anything that might trigger those painful re-experiencing symptoms. This includes avoiding certain people, places, conversations, activities, or even thoughts and feelings that are associated with the trauma.

The Full Spectrum of PTSD Symptoms

The third core cluster of PTSD symptoms is Negative Alterations in Cognition and Mood. This involves persistent and distorted beliefs about oneself or the world, such as “I am bad,” or “The world is utterly dangerous.” It can also include pervasive negative emotions like fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame, and a markedly diminished interest in activities that were once enjoyable. People with PTSD may feel detached or estranged from others and have a persistent inability to experience positive emotions, a state known as anhedonia. The fourth and final cluster is Alterations in Arousal and Reactivity. These symptoms reflect a body and mind in a constant state of high alert. They include irritable behavior and angry outbursts, reckless or self-destructive behavior, hypervigilance, an exaggerated startle response, problems with concentration, and sleep disturbances like insomnia.

It’s crucial to understand that PTSD is a normal reaction to an abnormal situation. The events that cause PTSD would be deeply distressing to almost anyone. Common examples include serious car accidents, natural disasters, violent personal assaults (like rape or mugging), witnessing a death or severe injury, or combat exposure. The diagnosis validates the profound and lasting impact such events can have on the human psyche. While the symptoms are debilitating, the framework of PTSD is relatively straightforward: a defined traumatic event leads to a set of predictable, though devastating, psychological responses aimed at survival.

What is CPTSD? The Legacy of Long-Term Captivity

If PTSD is the result of a single seismic shock, Complex PTSD is the erosion caused by years of smaller, repeated tremors. CPTSD arises from exposure to prolonged, repeated trauma from which there is little or no chance of escape. The individual is trapped, both physically and psychologically. This “captivity” is the central theme differentiating the causes of CPTSD vs PTSD. The trauma is not a one-off event but an inescapable relational and environmental context, often occurring during developmentally vulnerable times like childhood. It’s the difference between being in a car crash and being the passenger in a car driven by a reckless driver for your entire childhood—you never know when the next swerve will come, and you can’t get out.

The concept of CPTSD was first proposed in the 1990s by renowned psychiatrist Dr. Judith Herman. She argued that the existing PTSD model was insufficient to capture the profound psychological impact of chronic trauma. In such conditions, the trauma is not just an event that happened to you; it becomes the very fabric of your existence, shaping your identity, your understanding of relationships, and your view of the world. Because this trauma often occurs within caregiving systems or important relationships, it disrupts the very foundation of a person’s sense of self and their ability to connect with others in a healthy way. This is why CPTSD includes all the symptoms of PTSD but also extends far beyond them.

The Three Additional Pillars of CPTSD

The diagnosis of CPTSD includes the four symptom clusters of PTSD—Re-experiencing, Avoidance, Negative Alterations in Cognition and Mood, and Alterations in Arousal and Reactivity—but adds three fundamental and distinct pillars that define the complexity of the condition. The first of these is Affect Dysregulation. This means a profound inability to manage emotions effectively. Individuals with CPTSD don’t just feel sad or angry; they are often overwhelmed by intense, volatile, and seemingly uncontrollable emotional storms. They might swing from extreme rage to profound grief to paralyzing shame in a short period, or conversely, they may experience persistent numbness and a feeling of being completely detached from their emotions, as if observing life from behind a glass wall.

The second additional pillar is Negative Self-Concept. This goes beyond the negative beliefs seen in PTSD. It is a deep, pervasive, and often lifelong sense of being worthless, damaged, or guilty to the core. Shame is the dominant emotion, not fear. While a person with PTSD might think, “The world is dangerous,” a person with CPTSD thinks, “I am the danger, I am the problem, I am unlovable.” This identity is often forged in environments where the child was repeatedly told they were bad, unwanted, or at fault for the abuse they suffered. The third pillar is Disturbances in Relationships. Forming and maintaining healthy, trusting connections with others feels nearly impossible. This can manifest as persistent distrust and social isolation, a desperate need to cling to relationships even if they are abusive (repeating the familiar dynamic), or a complete loss of faith in humanity. The template for “relationship” was wired incorrectly during development, making safe connections feel foreign and threatening.

The Core Differences: A Head-to-Head Look at CPTSD vs PTSD

While CPTSD and PTSD are siblings in the trauma family, they are distinct diagnoses with critical differences that impact every aspect of a person’s experience and treatment. The most fundamental distinction lies in the origin story. The cause of PTSD is typically a single, identifiable traumatic incident or a short-duration event. The trauma is an outlier in the person’s life narrative. In contrast, the cause of CPTSD is chronic, repeated, and interpersonal trauma, where the victim is in a state of captivity, real or perceived. The trauma is not an outlier; it is the narrative, often woven throughout childhood or a long-term abusive relationship.

This difference in etiology creates a dramatic divergence in the symptom profile, particularly in the realm of identity and relationships. In PTSD, the sense of self, while negatively impacted, generally remains intact. A soldier with PTSD may believe the world is a nightmare, but he still knows he is a soldier who served his country. A rape survivor may feel dirty and afraid, but she does not necessarily forget that she is a competent, valuable person outside of the attack. The trauma is something that happened to them. In CPTSD, the trauma becomes who they are. The negative self-concept is all-encompassing; it’s a feeling of being fundamentally and irrevocably flawed. The trauma is not an event in their life; it is the lens through which they view their entire existence.

How Emotional Regulation and Relationships Differ

The challenges with emotional regulation also present differently. In PTSD, emotional dysregulation is often directly tied to trauma triggers. A veteran may have a rage outburst after hearing a car backfire, a clear trigger reminiscent of gunfire. Once the trigger has passed and they have calmed down, their emotional baseline may return. In CPTSD, affect dysregulation is a constant, pervasive feature of daily life. The emotional nervous system itself is disorganized and highly reactive. A minor criticism from a partner might trigger a cascade of shame and rage that is disproportionate to the event because it echoes a lifetime of being made to feel worthless. The person isn’t just reacting to a trigger; they are living in a body that is perpetually on high alert for relational threats.

Furthermore, the disturbances in relationships seen in CPTSD are far more profound than the social withdrawal and detachment seen in PTSD. Someone with PTSD might isolate because they fear triggers or feel others can’t understand them. Someone with CPTSD isolates because they believe, at their core, that they are unworthy of love and that other people are inherently untrustworthy or dangerous. They may unconsciously seek out abusive partners because the dynamic of being devalued feels familiar, like “home.” Or, they may become excessively dependent on a partner, mirroring the power dynamics of their original captivity. While PTSD can severely damage one’s ability to connect, CPTSD corrupts the very blueprint for what a relationship is supposed to be.

The Root Causes: Tracing the Origins of Trauma

Understanding the specific causes behind CPTSD and PTSD is essential for demystifying the conditions and reducing self-blame. For PTSD, the precipitating events, while horrifying, are usually time-limited and can often be articulated in a single story. The brain’s survival mechanisms—the fight, flight, freeze, or fawn responses—are activated in an overwhelming surge during the event. In PTSD, these mechanisms fail to reset, leaving the nervous system stuck in a traumatic loop. The memory of the event is not properly integrated and stored as a past experience; instead, it remains a raw, present-tense threat that can be reactivated by sensory cues.

The types of events that lead to PTSD are those that involve a direct threat to one’s life or physical integrity, or witnessing such a threat to others. This includes military combat, serious accidents, terrorist attacks, sudden loss of a loved one, and violent personal assaults like sexual assault or robbery. The key is the intensity of the threat and the individual’s perception of being in imminent danger. It’s important to note that not everyone who experiences such an event will develop PTSD; individual resilience, prior trauma history, and the availability of support systems after the event all play a significant role in determining the outcome.

The Inescapable Trap of CPTSD Causes

The causes of CPTSD, on the other hand, are characterized not by intensity alone, but by duration, repetition, and inescapability. The trauma is interpersonal, meaning it is inflicted by other people upon whom the victim is dependent or with whom they are in a close relationship. This creates a devastating double bind: the source of supposed safety is also the source of danger. The developing brain of a child is particularly vulnerable to this kind of trauma because it is literally shaping its wiring in an environment of fear and betrayal.

Classic examples of situations that lead to CPTSD include chronic childhood physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; long-term childhood neglect; living in a war zone or a community with pervasive violence; being a victim of long-term domestic violence or human trafficking; and being a prisoner of war or in a political captivity setting. In these scenarios, the trauma is not a single point on a timeline but the entire atmosphere. The child (or adult) cannot fight back effectively and cannot flee. Their survival often depends on developing complex coping strategies, such as dissociation, fawning (appeasing the abuser), or hyper-vigilance to the moods of others. These strategies, essential for survival at the time, become maladaptive and highly damaging in adulthood, forming the core symptoms of CPTSD.

Symptom Deep Dive: Beyond Flashbacks and Hypervigilance

When people think of trauma disorders, they often picture the classic PTSD symptoms: flashbacks and hypervigilance. While these are central to both PTSD and CPTSD, the full symptom picture, especially for CPTSD, is much broader and more insidious. In PTSD, re-experiencing symptoms are often sensory and vivid. A combat veteran might smell cordite and see the face of a fallen comrade during a flashback. A car accident survivor might feel the jarring impact and hear the screech of tires when a car pulls out in front of them. These intrusions are often unmistakably linked to the original event.

For someone with CPTSD, re-experiencing can be more diffuse and emotional. They may not have clear, cinematic flashbacks of a specific event, but rather, they may be plunged into intense emotional states—overwhelming shame, primordial terror, or bottomless grief—that feel disconnected from the present moment but are emotional echoes of their past. These are sometimes called “emotional flashbacks.” In an emotional flashback, there is no visual component; the person is simply hijacked by the felt sense of the original traumatic environment. They feel small, helpless, and terrified, just as they did as a child, but without knowing why.

The Unique and Debilitating Symptoms of CPTSD

This is where the additional symptoms of CPTSD truly distinguish it. The affect dysregulation means their emotional thermostat is broken. They don’t just get angry; they are consumed by a rage that feels terrifying. They don’t just feel sad; they collapse into a state of hopeless despair. Conversely, they may shut down completely, feeling numb and disconnected, unable to access any emotions at all. This rollercoaster is exhausting and makes daily functioning incredibly difficult. The negative self-concept is a voice in their head that never stops, constantly critiquing, shaming, and belittling them. It’s a deeply held conviction of inner badness that is resistant to logic or external validation.

Perhaps the most heartbreaking symptom is the disturbances in relationships. For a person with CPTSD, the world of human connection is a minefield. They may exhibit an intense need for a savior, becoming overly dependent on a partner, while simultaneously being terrified of abandonment. They may be distrustful to the point of paranoia, constantly testing their partner’s loyalty or pushing them away preemptively. They often have a poor “picker,” finding themselves in relationships with emotionally unavailable or abusive people because that dynamic feels familiar. They may struggle immensely with boundaries, either having none and being easily exploited, or having walls so high that no one can get in. This relational damage is often the source of the greatest pain in their adult lives, creating a vicious cycle of re-traumatization.

The Ultimate Guide to Dysport vs Botox: Choosing the Right Neurotoxin for You

The Path to Diagnosis: Why Getting It Right Matters

The process of diagnosing CPTSD and PTSD is a critical step on the road to recovery, yet it is fraught with challenges. PTSD is a recognized diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), the primary diagnostic tool used in the United States. A clinician will assess for the presence of the four symptom clusters we discussed earlier, ensuring they have persisted for over a month and cause significant distress. The diagnosis is relatively straightforward if the clinician is trauma-informed.

CPTSD, however, has a more complicated diagnostic status. It is not currently a standalone diagnosis in the DSM-5. This has been a point of significant controversy and advocacy within the mental health field. Many experts argue that forcing CPTSD into the PTSD box leads to misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment. Instead, CPTSD is recognized in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11), published by the World Health Organization. The ICD-11 clearly distinguishes CPTSD as a separate disorder, characterized by the symptoms of PTSD plus the three additional pillars of affect dysregulation, negative self-concept, and interpersonal problems.

The Consequences of Misdiagnosis

This discrepancy between diagnostic manuals has real-world consequences. Many patients with CPTSD are diagnosed with PTSD, which is better known. Others may be misdiagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), due to the overlapping symptoms of emotional dysregulation and unstable relationships. While CPTSD and BPD can co-occur, they are distinct conditions with different core origins. A misdiagnosis can lead to ineffective or even harmful treatment. For example, a person with CPTSD whose primary issue is a fractured sense of self rooted in childhood trauma needs a different therapeutic approach than someone whose PTSD stems from a single adult assault.

This is why finding a mental health professional who is knowledgeable about complex trauma is absolutely essential. A skilled therapist will take a thorough life history, not just ask about the “worst” thing that ever happened. They will listen for patterns of chronic, inescapable stress and will assess for the core features of CPTSD, such as pervasive shame and chronic relational difficulties. Getting the correct diagnosis is not about collecting a label; it’s about validating a person’s entire life experience and unlocking the most effective path to healing. It tells the patient, “Your suffering makes sense. Your symptoms are a predictable response to an unbearable situation, and there is a way forward.”

Treatment and Healing: Tailoring the Approach to the Trauma

Healing from trauma is always a journey, not a destination, and the roadmap for that journey differs significantly for CPTSD vs PTSD. For both, the gold-standard treatment is trauma-focused therapy, but the emphasis and pacing must be adapted to the complexity of the wounds. For PTSD, treatments often focus directly on processing the memory of the specific traumatic event. The goal is to help the brain properly store the memory so that it is filed away as a past event rather than experienced as a current threat.

Highly effective, evidence-based treatments for PTSD include Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), which helps patients challenge and reframe unhelpful beliefs about the trauma, and Prolonged Exposure (PE) therapy, which involves safely and gradually confronting trauma-related memories and situations to reduce their power. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is another powerful modality that uses bilateral stimulation (like side-to-side eye movements) to help the brain reprocess traumatic memories, allowing them to be integrated in a less distressing way. These therapies are often shorter-term and highly structured, targeting the specific event and its associated symptoms.

The Longer, More Nuanced Road for CPTSD Recovery

Treating CPTSD requires a more layered and often longer-term approach. Simply processing one or two traumatic memories is insufficient because the trauma is not a discrete event; it’s the foundation of the person’s identity and relational style. Treatment for CPTSD must address the core disturbances: the shattered self-image, the dysregulated nervous system, and the broken relational template. While EMDR and CPT can be helpful components, they are often used within a broader, phase-oriented model.

The first phase of CPTSD treatment is always safety and stabilization. This involves establishing a safe therapeutic relationship, learning crucial skills for emotion regulation (often drawn from Dialectical Behavior Therapy or DBT), and developing distress tolerance. This phase might include learning how to self-soothe, how to identify and name emotions, and how to set healthy boundaries. It’s about building a foundation of internal safety before ever delving into traumatic memories. The second phase involves processing traumatic memories in a careful, titrated way, using modalities like EMDR or parts work therapies. The final phase is reintegration and recovery, which focuses on building a new, positive identity, learning how to engage in healthy relationships, and finding meaning and purpose beyond the trauma.

Living and Thriving: Management Strategies for Daily Life

Beyond the therapist’s office, managing the symptoms of CPTSD and PTSD is a daily practice that empowers individuals to reclaim their lives. For both conditions, establishing a routine is paramount. The nervous system craves predictability, and a consistent daily structure for sleep, meals, work, and relaxation can provide a sense of safety and control. Mindfulness and grounding techniques are also invaluable tools. When flashbacks or emotional storms hit, practices like the 5-4-3-2-1 grounding exercise (naming five things you can see, four you can touch, three you can hear, two you can smell, and one you can taste) can pull the brain out of the past and into the safety of the present moment.

Physical self-care is non-negotiable in trauma recovery. Trauma lives in the body, so somatic (body-based) practices are essential. Regular, gentle exercise like walking, yoga, or swimming can help discharge pent-up fight-or-flight energy and regulate the nervous system. Prioritizing sleep hygiene is critical, as sleep disturbances are a core symptom of both disorders. A balanced diet and avoiding mood-altering substances like alcohol and drugs, which can worsen symptoms, are also key components of a management plan.

The Role of Community and Self-Compassion

For individuals with CPTSD, whose wounds are primarily relational, the management strategy must include a conscious effort to build healthy social connections. This can feel terrifying, but it is the antidote to the poison of isolation. This doesn’t mean having a wide circle of friends; it can mean finding one or two safe, trustworthy people with whom to be authentic. Support groups, either in-person or online, can be incredibly validating, as they provide a space to connect with others who “get it” without needing explanation.

Perhaps the most important management strategy for CPTSD, in particular, is the cultivation of self-compassion. The inner critic in CPTSD is brutal and relentless. Actively practicing self-compassion—talking to oneself with the kindness and understanding one would offer a dear friend—is a radical act of healing. It directly challenges the core symptom of a negative self-concept. This is hard, ongoing work, but over time, it can soften the sharp edges of shame and build a new, compassionate inner voice. Healing is not about erasing the past, but about building a life in the present that is rich, meaningful, and defined not by the trauma, but by one’s strength and resilience.

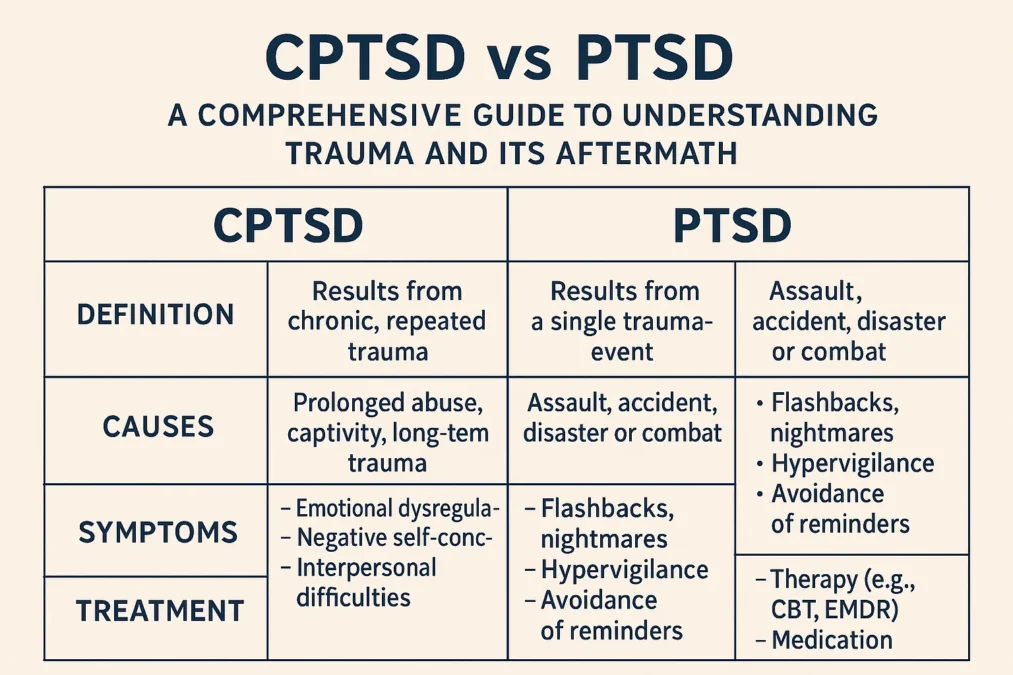

A Comparative Table: CPTSD vs PTSD at a Glance

| Feature | PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) | CPTSD (Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Cause | A single, life-threatening event or short-duration trauma. | Prolonged, repeated trauma from which there is no escape (e.g., childhood abuse, captivity). |

| Sense of Self | Generally remains intact, though negatively impacted. | Pervasively negative; deep feelings of shame, worthlessness, and being fundamentally flawed. |

| Emotional Regulation | Dysregulation is often tied to specific trauma triggers. | Chronic affect dysregulation; persistent, severe difficulty managing emotions. |

| Relationships | Withdrawal and detachment due to lack of understanding or fear of triggers. | Profound disturbances; intense distrust, fear of abandonment, repeated patterns of abusive relationships. |

| View of the World | The world is dangerous and unpredictable. | The world is dangerous, and the self is helpless, worthless, and deserving of the trauma. |

| Primary Focus of Treatment | Processing the memory of the specific traumatic event. | A phased approach: 1) Safety & Stabilization, 2) Trauma Processing, 3) Reintegration. |

Voices of Understanding: Quotes on Trauma

“The fundamental premise of CPTSD is that it is easier to manage the reality of ongoing abuse if you decide that you are a terrible, deserving person, than it is to face the terrifying reality that the person who is supposed to love and protect you is capricious and dangerous.” — Pete Walker, M.A., Psychotherapist and author of ‘Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving’

“Trauma is not what happens to you, but what happens inside you as a result of what happened to you. Trauma is the scarring that makes you less flexible, more rigid, less feeling and more defended.” — Dr. Gabor Maté, Physician and author specializing in trauma and addiction

“Recognizing the ways in which trauma has shaped our lives does not mean we are damaged or defective. It means we are human, and we have survived.” — Resmaa Menakem, Therapist and author of ‘My Grandmother’s Hands’

Frequently Asked Questions About CPTSD vs PTSD

What is the main difference between CPTSD and PTSD?

The main difference between CPTSD and PTSD lies in the cause and the complexity of symptoms. PTSD typically stems from a single, distinct traumatic event, and its symptoms are clustered around re-experiencing that event, avoidance, negative mood, and hyperarousal. CPTSD, on the other hand, results from prolonged, repeated trauma from which there is little chance of escape, such as chronic childhood abuse. It includes all the symptoms of PTSD but adds three more: severe difficulties with emotional regulation, a profoundly negative self-concept, and persistent challenges in forming and maintaining relationships.

Can you have both CPTSD and PTSD?

Yes, it is possible for an individual to have both conditions. This can occur if a person with a history of chronic trauma that led to CPTSD later experiences a separate, distinct traumatic event that meets the criteria for PTSD. For example, someone who endured years of childhood emotional neglect (leading to CPTSD) might later be involved in a serious car accident (leading to PTSD). In such cases, the symptoms can overlap and interact, making a comprehensive assessment by a trauma-informed clinician essential for developing an effective treatment plan that addresses both the complex relational trauma and the single-incident trauma.

Is CPTSD more severe than PTSD?

It is not necessarily helpful to think of CPTSD as “more severe” than PTSD. Both are severe, debilitating, and valid mental health conditions that cause immense suffering. However, CPTSD is often considered more complex because it affects the very core of a person’s identity and their capacity for relationship. The damage is more pervasive, impacting nearly every area of functioning. While a person with PTSD may be able to point to a specific event that ” broke” them, a person with CPTSD often feels that they were never whole to begin with, which requires a different, often longer, therapeutic approach to healing.

How is emotional flashback different from a PTSD flashback?

A classic PTSD flashback is often a sensory-rich, dissociative experience where the person feels and acts as if they are literally reliving the traumatic event. They may see, hear, and smell things from the past as if they are happening in the present. An emotional flashback, which is common in CPTSD, is different. There is typically no visual or auditory component. Instead, the person is suddenly and overwhelmingly engulfed by intense emotions from the past—such as terror, shame, despair, or rage—without a clear memory or trigger. They feel the way they did as a helpless child, but they may not understand why, which can be confusing and frightening.

What is the first step for someone who thinks they may have CPTSD?

The first and most courageous step is to seek out a mental health professional for an assessment. Look specifically for a therapist, psychologist, or psychiatrist who lists expertise in “trauma,” “complex trauma,” “CPTSD,” or “PTSD.” Be prepared to discuss not just the “worst” things that have happened to you, but the overall pattern of your childhood and important relationships. Reading books by experts like Judith Herman or Pete Walker can also provide validation and a framework for understanding your experience. Remember, reaching out for help is a sign of strength, not weakness. It is the first act of reclaiming your life from the grip of past trauma.

Conclusion

The journey of understanding CPTSD vs PTSD is one of moving from a black-and-white picture of trauma to one rendered in full, complex color. PTSD is a vital diagnosis that captures the shattering impact of a single, terrifying event. But for those whose suffering was not a single storm but a long, cold winter, CPTSD provides a name, a validation, and a framework for their profound and pervasive pain. It acknowledges that trauma can fracture not just your sense of safety, but your very identity and your ability to connect with others.

Knowing the difference is more than clinical semantics; it is the key that unlocks the right door to healing. It guides a survivor toward the specific therapies and support systems they need, whether that’s targeted processing of a specific memory or the long, compassionate work of rebuilding a shattered self from the ground up. If you see yourself in the descriptions of CPTSD, please know that your pain is real, it is understandable, and you are not broken beyond repair. Healing from complex trauma is a journey of coming home to yourself—of learning to soothe the terrified child within, quiet the critical inner voice, and slowly, bravely, learn to trust in the possibility of safe connection. The path is challenging, but it is a path toward a life defined not by what was done to you, but by the strength, wisdom, and compassion you have cultivated in its wake.