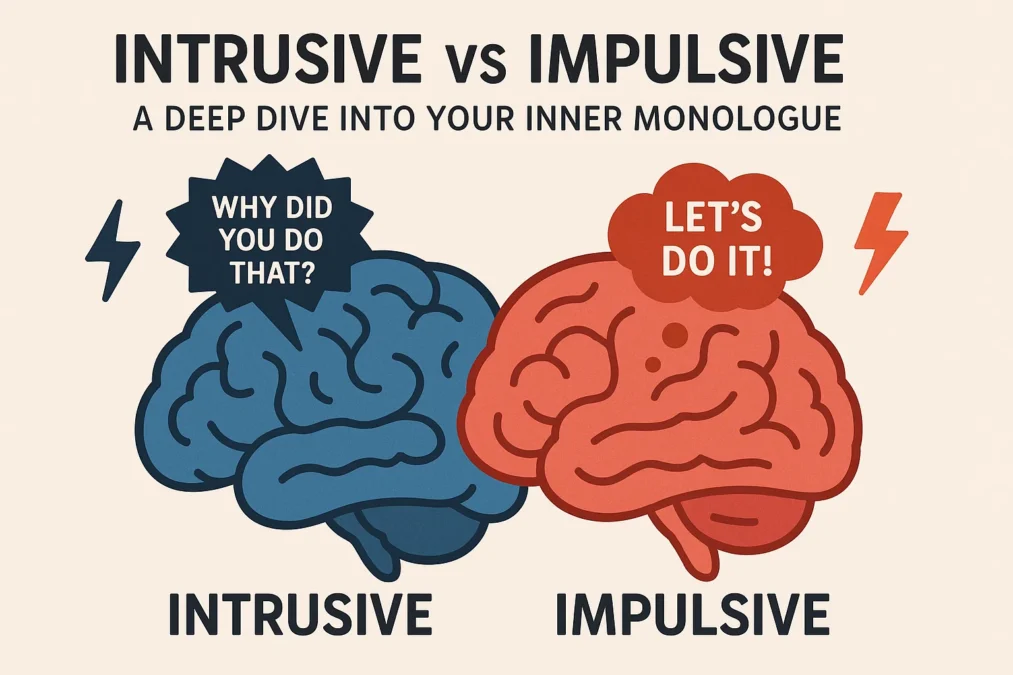

Have you ever been driving over a bridge and, out of nowhere, had a fleeting image of swerving into the railing? Or maybe you’ve been in a quiet meeting and been suddenly struck by an overwhelming urge to shout something completely inappropriate? If so, you’ve had a firsthand encounter with the uninvited guests of the human mind. These unexpected mental events are incredibly common, yet they can be deeply unsettling. Most people lump them together under the banner of “weird thoughts,” but understanding the distinct difference between intrusive vs impulsive thoughts is a critical first step toward demystifying your own mental landscape and improving your psychological health.

While they might feel similar in their suddenness and intensity, intrusive and impulsive thoughts originate from different places, serve different functions, and require different responses. Confusing the two can lead to unnecessary anxiety or, conversely, a failure to address potentially harmful behaviors. This article is your comprehensive guide to navigating this complex terrain. We will explore the definitions, causes, and characteristics of each type of thought, provide a clear comparison, and offer practical strategies for managing them. By the end, you will have a expert-level understanding of why your mind generates these thoughts and how you can relate to them in a healthier, more empowered way.

What Are Intrusive Thoughts?

Let’s start by diving into the world of intrusive thoughts. Imagine your mind as a serene, flowing stream. An intrusive thought is like a random piece of debris—a fallen leaf, a stray twig—that suddenly appears on the water’s surface, disrupting the calm. It’s an unwanted, involuntary thought, image, or urge that can feel shocking, bizarre, or even horrifying. These thoughts often pop into consciousness without any warning and are typically inconsistent with a person’s values and character. Common themes include thoughts of violence (harming oneself or others), sexual thoughts that are taboo or disturbing, blasphemous thoughts for religious individuals, or fears of contamination and making catastrophic mistakes.

The key hallmark of an intrusive thought is its unwanted nature. They are ego-dystonic, meaning they are alien to your sense of self. A loving parent might have a sudden, graphic thought of dropping their baby. A gentle person might have an image of pushing a stranger in front of a train. The content is so jarring precisely because it clashes with who they are. This mismatch is what causes the intense distress, fear, and anxiety that typically follow. The person thinks, “Where did that come from? Does this mean I’m a bad person?” It’s crucial to understand that the thought itself is not the problem; it’s the alarm you sound in response to it that creates the suffering.

Why Do We Have Intrusive Thoughts?

The prevalence of intrusive thoughts suggests they are a normal part of the human experience. Research indicates that almost everyone experiences them from time to time. One theory is that they are a byproduct of our brain’s threat-detection system. Your brain is constantly scanning for potential dangers, and sometimes it generates a “what if” scenario so you can be prepared to avoid it. For example, a quick thought of “what if I slip off this cliff?” near a edge is your brain’s blunt way of saying, “Be careful, stay back.” The problem arises when the brain’s alarm system becomes oversensitive, misfiring and presenting these hypothetical dangers as immediate threats that need to be neutralized.

For most people, these thoughts come and go without much fanfare. They are dismissed as mental static. However, for individuals with anxiety disorders, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), or depression, these thoughts can become sticky and pervasive. In conditions like OCD, the intrusive thought becomes an “obsession”—a recurring, persistent thought that causes significant anxiety. The individual then feels compelled to perform a “compulsion”—a mental or physical act—to neutralize the anxiety caused by the thought. This creates a vicious cycle where the fear of the thought gives the thought more power, ensuring its return.

The Emotional Aftermath of an Intrusive Thought

The emotional impact of an intrusive thought is often more damaging than the thought itself. Because the content is so contrary to a person’s identity, it triggers a wave of guilt, shame, and fear. The individual may engage in endless self-interrogation, trying to figure out what the thought “means” about their hidden desires or character. This process, known as thought-action fusion, is the cognitive distortion that believing a thought is morally equivalent to carrying out the action or that thinking about something makes it more likely to happen.

This is why the common advice to “just ignore” intrusive thoughts is often ineffective and can even be counterproductive. Trying to suppress a thought—to forcefully push it out of your mind—is like trying to hold a beach ball underwater. The more effort you exert, the more explosively it will eventually反弹 back to the surface. This phenomenon, known as ironic process theory, explains why telling yourself “don’t think about a pink elephant” immediately makes you think of a pink elephant. The struggle and avoidance give the intrusive thought more significance and power, trapping the person in a cycle of anxiety, suppression, and relief-seeking behaviors that only reinforce the problem.

What Are Impulsive Thoughts?

Now, let’s turn our attention to impulsive thoughts. If an intrusive thought is an unwelcome piece of debris in your mental stream, an impulsive thought is a strong, sudden current that tries to pull you in a particular direction. These thoughts are characterized by a powerful, often irresistible urge to perform an action. They are typically about immediate gratification or relief. The thought isn’t a disturbing image of “what if,” but a compelling “I need to do this now.” Examples include the urge to buy something you can’t afford, to send a angry text message, to blurt out a secret, to skip an important responsibility in favor of something fun, or to engage in a risky behavior for a thrill.

Unlike intrusive thoughts, impulsive thoughts can often feel ego-syntonic, meaning they feel aligned with your immediate desires or mood, even if they conflict with your long-term goals. In the heat of the moment, that urge to buy the new gadget feels good because it promises a dopamine hit. The impulse to yell at someone feels justified because you’re angry. The distress associated with impulsive thoughts usually comes after the action is taken—the guilt of overspending, the regret of sending the text, the consequences of skipping work. The struggle is in the moment of temptation: the fight between the immediate urge and your better judgment.

The Neuroscience of Impulsivity

Impulsive thoughts are deeply rooted in the brain’s reward system. They are driven by the desire for instant reward and the avoidance of immediate discomfort. Neurologically, this involves a tug-of-war between the limbic system (particularly the amygdala), which processes emotions and seeks reward, and the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive functions like planning, impulse control, and considering long-term consequences. When an impulsive thought arises, it’s often because the emotional, reward-seeking part of the brain has temporarily overpowered the rational, regulatory part.

This is why impulsivity is a key feature in several neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions. For individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), the prefrontal cortex may have inherent difficulties with regulation, making impulsive thoughts more frequent and harder to resist. In conditions like Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) or substance use disorders, impulsive actions are often used as a maladaptive way to cope with intense, overwhelming emotions. The impulsive thought (“I need a drink”) is a shortcut to numbing emotional pain. The brain learns that the action provides quick, albeit temporary, relief, reinforcing the impulsivity loop.

The Consequences of Acting on Impulse

The primary difference in the aftermath of impulsive thoughts versus intrusive thoughts lies in the sequence of events. With intrusive thoughts, the distress leads to avoidance or neutralization. With impulsive thoughts, the (potential) distress follows the action. The classic example is buyer’s remorse: the thrill of the purchase is followed by anxiety about the credit card bill. Another common scenario is social regret—saying something hurtful in anger and immediately wishing you could take it back.

When impulsive actions become a pattern, they can severely impact a person’s life, leading to financial trouble, damaged relationships, professional setbacks, and physical harm. The individual may feel a lack of control over their own life, as if they are constantly cleaning up messes created by their own momentary lapses in judgment. This can erode self-esteem and lead to a negative self-image (“I have no self-control”). However, it’s important to recognize that impulsivity exists on a spectrum. Everyone acts impulsively from time to time; it becomes a clinical concern when it is chronic, severe, and leads to significant functional impairment.

Trypsin vs Chymotrypsin on the MCAT: The Ultimate Guide to Mastering Digestive Enzymes

The Key Differences: A Side-by-Side Comparison

Understanding the theoretical definitions is one thing, but being able to distinguish between these thoughts in your daily life is another. The confusion between intrusive vs impulsive thoughts is understandable because they share the qualities of being sudden and automatic. However, their core nature, emotional tone, and the resulting behaviors are fundamentally different. Let’s break down these distinctions in a clear, comparative way.

The most reliable way to tell them apart is to examine your reaction to the thought. An intrusive thought triggers immediate fear, horror, or disgust. It feels like an invasion. You want to get rid of it, to push it away. You might think, “Oh my god, I would never do that!” An impulsive thought, in contrast, triggers a sense of desire, temptation, or a craving for release. It feels like a magnetic pull. You want to act on it, even if a small part of you knows you shouldn’t. The conflict is between the urge and your conscience, not between the thought and your entire identity.

A Comparative Table: Intrusive vs Impulsive Thoughts

| Feature | Intrusive Thoughts | Impulsive Thoughts |

|---|---|---|

| Core Nature | Unwanted, involuntary, and distressing. | Compelling urge for immediate action or gratification. |

| Thematic Content | Often violent, sexual, blasphemous, or fear-based. Taboo. | Often about spending, speaking, acting, or seeking sensation. |

| Relationship to Self | Ego-dystonic (feels alien, against one’s values). | Often ego-syntonic (feels aligned with immediate desires). |

| Primary Emotion | Anxiety, fear, disgust, shame. | Temptation, urgency, excitement, restlessness. |

| Goal of the Thought | To alert to a perceived (but false) threat. | To seek reward or relieve immediate tension. |

| Common Response | Avoidance, suppression, mental rituals (compulsions). | Giving in to the urge, acting on the impulse. |

| Timing of Distress | Distress occurs before and because of the thought. | Distress often occurs after acting on the thought (regret). |

| Associated Conditions | OCD, Anxiety Disorders, PTSD, Depression. | ADHD, BPD, Bipolar Disorder, Substance Use Disorders. |

Another critical distinction lies in what happens after the thought appears. The typical response to an intrusive thought is resistance. People might try to cancel it out with a “good” thought, seek reassurance from others that they aren’t a bad person, or avoid situations that might trigger the thought (e.g., a person with harm thoughts avoiding knives). The response to an impulsive thought, however, is often surrender. The individual may experience a brief internal struggle, but the pull of the potential reward is so strong that they act, often with little forethought. The regret and shame come later, which can then trigger a new cycle of negative emotions that may lead to further impulsive behavior as a coping mechanism.

How to Manage Intrusive Thoughts Effectively

Managing intrusive thoughts is not about eliminating them—that’s an impossible goal. Instead, the goal is to change your relationship with them, to rob them of their power to cause distress. The most effective, evidence-based approach for managing intrusive thoughts, especially within OCD, is a type of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) called Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) and mindfulness-based techniques. The core principle is to learn to accept the presence of the thought without engaging with it or trying to make it go away.

The first step is psychoeducation—simply understanding that these thoughts are normal and meaningless. Recognizing that having a thought about harming someone does not mean you are a violent person is liberating. It’s the difference between seeing the thought as a dangerous warning sign and seeing it as meaningless mental spam. This cognitive shift is powerful. From there, mindfulness teaches you to observe the thought without judgment. You can learn to label it—”Ah, that’s an intrusive thought”—and let it pass by, like a cloud moving across the sky, without getting tangled up in its content.

Practical Strategies for Daily Life

When an intrusive thought strikes, instead of fighting it, try these techniques. Practice acknowledging it neutrally: “I’m having the thought that I might shout in this quiet room.” This creates a small but crucial distance between you and the thought. You are not the thought; you are the observer of the thought. Another powerful tool is scheduled worry. If a thought is persistent, tell yourself, “I’m not going to engage with this now, but I will think about it for 10 minutes at 5 PM.” Often, by 5 PM, the thought has lost its urgency. This breaks the cycle of immediate, anxious engagement.

For more severe cases, particularly with OCD, ERP is the gold standard. Under the guidance of a therapist, this involves gradually and systematically exposing yourself to the thoughts or situations that trigger your obsessions (the exposure) and then voluntarily refusing to perform the compulsive ritual that eases your anxiety (the response prevention). For example, someone with contamination fears might touch a doorknob and then resist the urge to wash their hands for a predetermined period. Through this process, the brain learns that the feared outcome does not occur and that the anxiety will naturally subside on its own without the compulsion. This rewires the neural pathways that have been reinforcing the OCD cycle.

How to Manage Impulsive Thoughts Effectively

Managing impulsive thoughts is less about passive observation and more about active intervention and skill-building. The goal is to strengthen your brain’s “pause button”—the prefrontal cortex—so it can catch up with the limbic system’s demand for immediate action. The key strategy here is to create a space between the impulse and the action. This is often called the “gap,” and widening this gap is the foundation of impulse control. Techniques from Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), which is highly effective for issues of emotional dysregulation and impulsivity, are particularly useful.

The most fundamental skill is mindfulness of the current emotion and urge. Just as with intrusive thoughts, the first step is to notice the impulse without judgment. “I am having an urge to send an angry email.” This simple act of naming it engages the rational brain and begins to slow down the automatic process. The next step is to buy yourself time. The “10-Minute Rule” is a brilliant, simple tool: when you feel an impulse, tell yourself you will wait 10 minutes before acting. If after 10 minutes you still want to do it, then you can reconsider. Most impulsive urges are like waves—they peak and then subside. The 10-minute delay allows the wave to crash and recede.

Building Your Impulse Control Muscle

Impulse control is like a muscle; it gets stronger with exercise. Beyond the 10-minute rule, other strategies can be highly effective. “Playing the tape through” is a cognitive technique where you force yourself to vividly imagine the consequences of acting on the impulse, not just the immediate reward. That urge to buy a new TV feels great now, but what does it look like when the credit card bill arrives? What will you have to sacrifice to pay for it? Making the long-term consequences feel real and immediate can dampen the power of the urge.

For recurring impulsive patterns, more structural changes are needed. This includes removing temptations from your environment (e.g., unsubscribing from shopping emails if you impulse spend, not keeping junk food in the house if you impulse eat) and pre-committing to decisions when you are in a calm state. For individuals with ADHD, treatment plans that may include medication can be transformative by improving the underlying neurobiological capacity for self-regulation. Therapy can also help in developing distress tolerance skills, so you have healthier ways to cope with intense emotions instead of turning to impulsive behaviors for relief.

When to Seek Professional Help

While both intrusive and impulsive thoughts are a normal part of the human experience, there is a clear line when they cross over from occasional quirks to signs of a underlying mental health condition. Knowing when to seek help is a sign of self-awareness and strength, not weakness. The general rule of thumb is to consider the impact these thoughts are having on your quality of life. Are they causing you significant distress? Are they taking up a lot of your time each day? Are they preventing you from working, maintaining relationships, or enjoying life? Are they leading you to engage in behaviors that are harmful to yourself or others?

For intrusive thoughts, professional help is strongly recommended if the thoughts are persistent, cause severe anxiety or shame, and especially if you find yourself engaging in compulsive behaviors (physical or mental) to neutralize them. This is a classic sign of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. For impulsive thoughts, it’s time to seek help if you consistently find it impossible to resist urges that lead to negative consequences, such as financial debt, substance abuse, broken relationships, or legal trouble. This could indicate conditions like ADHD, Borderline Personality Disorder, Bipolar Disorder (during manic episodes), or a substance use disorder.

What Kind of Help is Available?

The good news is that help is available and highly effective. The first step is usually to consult a primary care physician or a mental health professional like a psychologist or psychiatrist. They can provide a proper diagnosis and recommend a treatment plan. For intrusive thoughts driven by OCD or anxiety, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), specifically Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), is the frontline treatment. For impulsive thoughts related to ADHD, a combination of medication (like stimulants) and skills-based therapy (like CBT or DBT) is often most effective.

For conditions like BPD or bipolar disorder, specialized therapies like Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) are designed to directly target emotional dysregulation and impulsivity. A therapist can provide a safe space to understand the root causes of your thoughts, whether they are rooted in trauma, anxiety, or neurodivergence, and equip you with a personalized toolkit of strategies. Remember, seeking help is not about “fixing” a broken brain; it’s about learning to understand and work with the brain you have, building skills to live a more peaceful and fulfilling life.

The Bigger Picture: Embracing a Non-Judgmental Mindset

Whether you struggle more with intrusive or impulsive thoughts, the universal key to finding peace is cultivating a non-judgmental attitude toward your own mind. Our minds are thought-generating machines. They produce all kinds of content—brilliant, creative, mundane, strange, and disturbing. We tend to want to claim the “good” thoughts as our own and disown the “bad” ones. But this very act of judgment—of labeling thoughts as good or bad—is what creates much of our suffering. When you have a thought and then think, “I shouldn’t be thinking that!” you add a layer of secondary suffering on top of the initial discomfort.

Learning to see your thoughts as just thoughts—mental events that come and go—is a profound shift. It’s the difference between standing in a river and being battered by the waves versus sitting on the riverbank and watching the water flow by. This doesn’t mean you condone harmful actions; it means you stop terrorizing yourself for having a random, harmless neural firing. This approach, central to mindfulness and acceptance-based therapies, applies to both intrusive and impulsive thoughts. It allows you to see an impulsive urge without immediately acting on it, and it allows you to see an intrusive image without being consumed by fear.

The Journey of Self-Acceptance

This journey is not about achieving a perfectly quiet mind. That is an unrealistic and frustrating goal. The goal is to develop a different kind of relationship with the noise. It’s about learning to say, “There’s that thought again,” with a sense of familiarity and even compassion, rather than panic. When you stop fighting your thoughts, you conserve an enormous amount of mental energy that was previously spent on suppression, avoidance, and guilt. This freed-up energy can then be directed toward living your life according to your values—which is the ultimate antidote to both anxiety and impulsivity.

As you practice this non-judgmental stance, you may find that the thoughts themselves begin to lose their charge. They may still appear, but they become like background noise—present, but easy to tune out. You realize that you are not your thoughts. You are the conscious awareness behind them. This realization is the foundation of true mental resilience. It empowers you to acknowledge the entire spectrum of your inner experience without being controlled by it, allowing you to choose your actions wisely and live a life of greater intention and peace.

Conclusion

The landscape of the human mind is vast and complex, filled with a constant stream of thoughts, both welcome and unwelcome. Understanding the critical distinction between intrusive vs impulsive thoughts is a powerful tool for navigating this inner world. Intrusive thoughts are unwelcome invaders that cause fear and are met with resistance; impulsive thoughts are compelling urges toward immediate gratification that are often followed by regret. While they feel similar in their suddenness, their origins, emotional tones, and the behaviors they trigger are fundamentally different.

By learning to identify which type of thought you are dealing with, you can apply the appropriate response: mindful acceptance and non-engagement for intrusive thoughts, and strategic delay and consequence evaluation for impulsive thoughts. Remember, having these thoughts does not define you. Your character is determined by your conscious actions and values, not by the random, automatic content of your mind. Whether you seek self-help strategies or professional guidance, the path forward is one of self-compassion, education, and skill-building. By embracing a non-judgmental curiosity about your own mental processes, you can transform your relationship with your thoughts from one of fear and conflict to one of awareness and choice, ultimately leading to a calmer, more controlled, and fulfilling life.

Frequently Asked Questions About Intrusive vs Impulsive Thoughts

What is the main difference between an intrusive and an impulsive thought?

The main difference lies in how you experience and react to the thought. An intrusive thought is unwanted, distressing, and feels alien to your character. It causes immediate anxiety, and your instinct is to reject it and make it go away. An impulsive thought is a strong, compelling urge to act, often for immediate reward or relief. It feels tempting in the moment, and the struggle is to resist acting on it, with distress typically coming afterwards in the form of regret.

Can a thought be both intrusive and impulsive?

While they are distinct categories, the lines can sometimes blur, especially in certain conditions. For example, someone with OCD might have an intrusive thought about contamination, which then creates an overwhelming impulse to wash their hands (the compulsion). In this case, the initial thought is intrusive, but the response is an impulsive urge to perform a ritual. The key is to identify the primary nature of the initial thought: is it causing fear (intrusive) or creating a pull to act (impulsive)?

Does having intrusive thoughts mean I have OCD?

Not necessarily. Almost everyone experiences intrusive thoughts from time to time. They become a sign of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder when they become persistent, recurrent obsessions that cause extreme anxiety and lead to compulsive behaviors aimed at reducing that anxiety. If the thoughts and rituals are time-consuming (e.g., more than an hour a day) and significantly interfere with your daily life, it is a good idea to seek an evaluation from a mental health professional.

Are impulsive thoughts a sign of ADHD?

Impulsivity is a core symptom of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Individuals with ADHD often struggle with executive functions, which include impulse control. Therefore, frequent and difficult-to-manage impulsive thoughts and actions are very common in ADHD. This can manifest as impulsive speaking, spending, or decision-making. However, impulsivity is also a feature of other conditions, so a proper diagnosis from a clinician is important.

How can I explain these thoughts to a partner or friend without them worrying?

It can be challenging, but framing it correctly is key. You could say, “Sometimes I have random, upsetting thoughts that pop into my head that are completely against who I am. They’re called intrusive thoughts, and they’re actually very common. They don’t mean I want to act on them—in fact, they bother me because I don’t want to.” For impulsive thoughts, you might say, “I sometimes struggle with strong urges to do things without thinking them through, and I’m working on pausing before I act.” Normalizing the experience and emphasizing that you are managing it can help alleviate a loved one’s concerns.