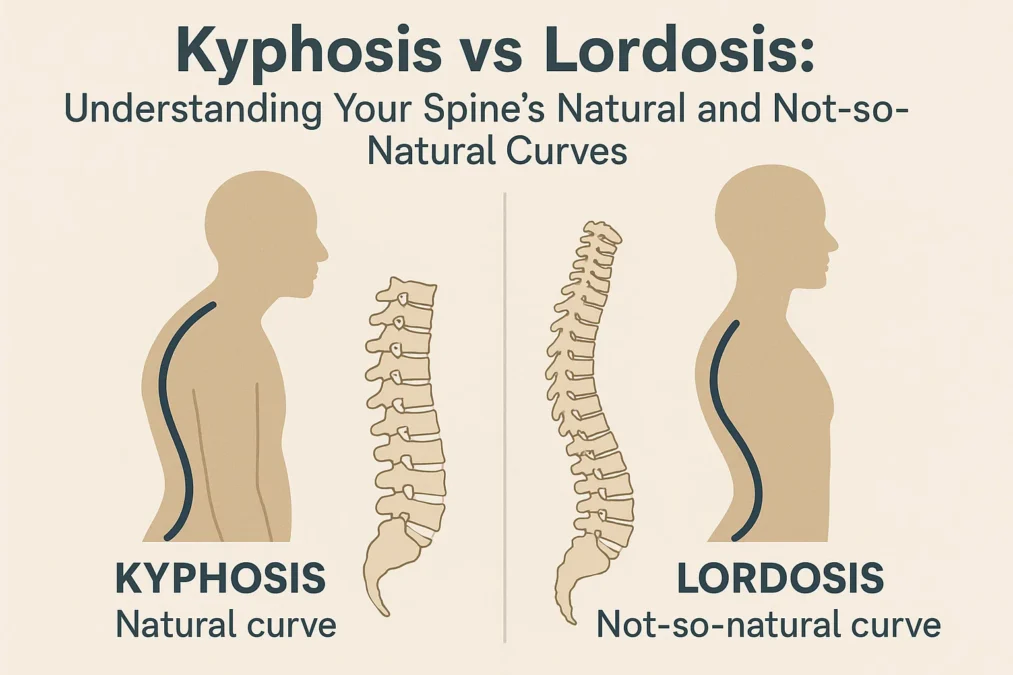

Have you ever wondered why your spine isn’t just a straight, rigid pole? That S-shaped curve you see from the side is a masterpiece of evolutionary engineering, designed to absorb shock, support your weight, and allow for a incredible range of motion. But sometimes, these curves can become exaggerated, leading to pain, postural issues, and a diagnosis that might sound confusing: kyphosis or lordosis.

Understanding the difference between kyphosis vs lordosis is the first step toward addressing spinal health concerns. While both terms describe abnormal curvatures of the spine, they refer to very specific issues in distinct regions of your back. It’s not just a matter of “bad posture”; these conditions can have deep-rooted causes and require different approaches to management and treatment. This comprehensive guide will demystify these two conditions, exploring everything from their basic definitions to their symptoms, causes, and the latest treatment options. We’ll dive deep into the comparison, so you can walk away with a clear, confident understanding of your spinal health.

Think of your spine as a sophisticated suspension system. The natural curves act like springs, cushioning the impact of every step you take. When these springs are balanced, everything works smoothly. But if one spring becomes too tight or too loose—if a curve becomes too pronounced—the entire system is thrown off balance. This is the essence of kyphosis vs lordosis. One affects the upper back, the other the lower back and neck, but both disrupt the spine’s harmonious function. Our journey through this topic will equip you with the knowledge to recognize the signs, seek appropriate care, and take proactive steps toward maintaining a strong and healthy spine for years to come.

What is the Normal Curvature of the Spine?

Before we can understand what goes wrong, we need to appreciate what’s right. A healthy spine, when viewed from the side, has four distinct natural curves that form a gentle “S” shape. These curves are categorized as either kyphotic or lordotic, which is why the kyphosis vs lordosis conversation can get tricky—they are also the names for the normal curves!

The spine is divided into three main regions from top to bottom: the cervical (neck), thoracic (upper and mid-back), and lumbar (lower back) spine, with the sacrum and coccyx (tailbone) at the very base. A normal cervical lordosis is a curve that bends inward, toward the front of the body. The thoracic kyphosis is a curve that bends outward, toward the back of the body. The lumbar lordosis is another inward curve, and the sacral kyphosis is a fused outward curve. This alternating pattern is crucial. It distributes mechanical stress evenly during movement, acting as a shock absorber far more effective than a straight column could ever be.

This elegant design allows us to walk, run, and jump without jarring our brains with every step. It also minimizes the workload on our muscles. When the spine is properly aligned, the bones bear the weight efficiently. When the curves are exaggerated or flattened, muscles have to work overtime to keep us upright, leading to fatigue, strain, and pain. So, when we talk about kyphosis vs lordosis as medical conditions, we are really discussing an exaggeration or reduction of these otherwise normal and essential curves. It’s a matter of degree and impact, not just the presence of the curve itself.

Diving Deep into Kyphosis

Kyphosis is a condition characterized by an excessive outward curvature of the spine, resulting in a rounded or hunched upper back. While a small degree of rounding in the thoracic spine is normal, kyphosis refers to a curve that is larger than typical—often defined as a curvature exceeding 50 degrees when measured on an X-ray. This exaggerated rounding can range from a minor postural issue to a severe deformity that affects breathing and organ function. The visual hallmark is often a “hunchback” or rounded shoulders appearance, but the implications run much deeper.

The experience of kyphosis varies greatly from person to person. Some individuals may have no symptoms other than the visible change in their posture. Others may experience persistent back pain, stiffness, and a feeling of fatigue in the back muscles. In advanced cases, the rounding can be so severe that it puts pressure on the lungs and abdomen, leading to shortness of breath or digestive issues. Understanding the specific type of kyphosis is key to understanding its cause and potential treatment, which is a central point in the discussion of kyphosis vs lordosis.

The Primary Causes and Types of Kyphosis

Kyphosis isn’t a one-size-fits-all condition. It develops for a variety of reasons, which helps doctors classify it into different types. The most common form is postural kyphosis, which often develops during adolescence. This is typically due to chronic poor posture—slouching in chairs, carrying heavy backpacks, and hunching over electronic devices. The good news is that this type is often flexible and can be improved significantly with physical therapy and conscious postural correction. The muscles and ligaments adapt to the slouched position, but they can be retrained.

More structural forms of kyphosis include Scheuermann’s kyphosis, a condition that arises during the growth spurt before puberty. Here, the vertebrae develop in a wedge shape instead of a rectangular shape, creating a rigid, sharp angular curve that doesn’t straighten when the person lies down. Another major cause is degenerative kyphosis, which occurs in older adults due to wear-and-tear on the spine. Conditions like osteoporosis, where bones become weak and brittle, can lead to compression fractures in the vertebrae, causing them to collapse and the spine to curve forward. Other causes include congenital issues (present at birth), traumatic injuries, or diseases like cancer or infections that affect the spinal bones.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Kyphosis

The symptoms of kyphosis can be subtle at first and are often dismissed as general back pain or the effects of aging. The most obvious sign is a visible roundness or hump on the upper back, which may be noticed by a family member or doctor before the individual themselves. Clothing may not hang properly, and one shoulder might appear higher than the other. Beyond the visual cues, people with kyphosis often report a dull, aching pain in the upper back, which can worsen after long periods of sitting or standing.

As the curvature progresses, the symptoms can become more pronounced. The body compensates for the forward pull of the upper body, which can lead to strain and pain in the neck and lower back—a key point of interaction in the overall kyphosis vs lordosis dynamic. In severe cases, individuals may experience neurological symptoms like numbness, tingling, or weakness in the legs if the curve begins to impinge on the spinal cord. The restricted space in the chest cavity can also lead to breathing difficulties, as the lungs may not have enough room to fully expand. Early recognition of these symptoms is critical for effective management.

Diagnosis and Treatment Pathways for Kyphosis

Diagnosing kyphosis typically begins with a physical examination. Your doctor will observe your posture from the front, back, and side, and may ask you to bend forward (the Adams Forward Bend Test) to better assess the curve. They will check your range of motion, reflexes, and muscle strength. If a significant curvature is suspected, the next step is usually an X-ray to measure the exact angle of the curve (Cobb angle) and to examine the shape of the vertebrae. In complex cases, an MRI or CT scan might be ordered to get a detailed look at the spinal cord and nerves.

Treatment for kyphosis is entirely dependent on the cause, severity, and whether the patient is still growing. For mild postural kyphosis, the focus is on non-invasive interventions. This includes physical therapy to strengthen the core, back, and shoulder muscles, which act as a natural brace for the spine. Postural training and exercises are fundamental. For adolescents with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who are still growing, a brace may be used to prevent the curve from worsening. For severe, painful, or progressive curves—especially those causing neurological or respiratory issues—spinal fusion surgery may be considered. This major procedure aims to straighten and fuse the curved vertebrae together using metal rods and screws, creating a solid bone mass that prevents further curvature.

Unpacking the Details of Lordosis

Lordosis, in contrast to kyphosis, is an excessive inward curvature of the spine. While a certain degree of inward curve in the cervical and lumbar regions is normal and healthy, lordosis refers to an exaggerated arch. This condition most commonly affects the lower back, known as lumbar lordosis or “swayback,” but can also occur in the neck (cervical lordosis). When you look at someone with significant lumbar lordosis from the side, you’ll notice a pronounced C-shaped curve, with their abdomen and buttocks protruding more than usual.

This exaggerated arch places unusual stress on the structures of the spine. The muscles in the lower back become tight and hyperactive, while the abdominal and gluteal muscles often become weak and stretched. This muscle imbalance perpetuates the abnormal curve, creating a cycle of discomfort. The condition can cause significant pain, not just in the lower back, but also referred pain into the buttocks and legs. Understanding the mechanics of lordosis is just as important as understanding kyphosis when evaluating the overall kyphosis vs lordosis picture, as the two conditions can sometimes be linked, with one developing to compensate for the other.

Common Causes and Variations of Lordosis

Just like kyphosis, lordosis has multiple potential causes. One of the most common is postural, often related to obesity. Excess weight, particularly around the abdomen, pulls the pelvis forward, increasing the curve in the lower back to maintain balance. Similarly, pregnancy can cause temporary lordosis as the body adapts to the shifting center of gravity. Another major cause is muscle imbalance, particularly weak core muscles and tight hip flexors. When the muscles that should stabilize the pelvis are weak, the hip flexors pull the pelvis into an anterior tilt, creating that characteristic swayback posture.

Other causes are more structural. Spondylolisthesis, a condition where one vertebra slips forward over the one below it, can lead to lordosis. Diseases like osteoporosis or discitis (inflammation of the spinal discs) can weaken the spinal structures. Hip disorders, such as congenital hip dysplasia, can also affect pelvic alignment and lead to a compensatory lordotic curve. It’s also common for someone with significant kyphosis in their thoracic spine to develop a compensatory lumbar lordosis; the body automatically arches the lower back more to keep the head aligned over the pelvis, which is a perfect example of how kyphosis vs lordosis are not always separate issues.

Identifying the Signs and Symptoms of Lordosis

The most noticeable symptom of lordosis is the change in posture. The individual will have a pronounced arch in the lower back, with the buttocks sticking out and the stomach protruding. There is often a visible gap between the lower back and the floor when lying on your back on a hard surface. Beyond the appearance, people with lordosis frequently experience lower back pain. This pain is often a dull ache that worsens with activities that exaggerate the curve, such as standing for long periods or arching the back. The pain may also radiate into the buttocks and down the legs if nerve compression is involved.

The muscle imbalances that cause and result from lordosis lead to their own set of symptoms. Tightness and stiffness in the lower back and hip flexors are very common. Conversely, a feeling of weakness in the abdominals and glutes is typical. This can make certain movements, like squats or even walking, less efficient and more fatiguing. In severe cases, especially those related to neurological conditions, individuals may experience a loss of bladder or bowel control, numbness, or a “pins and needles” sensation in the legs, which requires immediate medical attention.

How Lordosis is Diagnosed and Treated

The diagnostic process for lordosis mirrors that of kyphosis. A doctor will start with a medical history and a physical exam, observing the posture and checking for range of motion. They may slide a hand under the patient’s lower back while they are lying down to assess the depth of the curve. The Adams Forward Bend Test is less specific for lordosis than for kyphosis, but the overall spinal alignment is carefully evaluated. X-rays are used to confirm the diagnosis and measure the degree of the curvature, while CT or MRI scans can help identify any underlying causes like disc problems or nerve compression.

Treatment for lordosis is overwhelmingly conservative and focused on addressing the root cause. For postural and muscular lordosis, physical therapy is the cornerstone of treatment. A physical therapist will design a program to strengthen the core muscles (abdominals and glutes) and stretch the tight muscles (hip flexors and lower back). This helps to pull the pelvis back into a neutral position, reducing the excessive arch. Weight loss is often a critical recommendation for individuals whose lordosis is exacerbated by obesity. Pain and inflammation can be managed with over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications. In the rare cases where lordosis is severe, progressive, or caused by a structural problem that doesn’t respond to conservative care, surgical options similar to those for kyphosis, such as spinal fusion, may be explored.

Central Heterochromia vs Hazel Eyes: Understanding the Differences

Kyphosis vs Lordosis: A Head-to-Head Comparison

Now that we have a solid understanding of each condition individually, let’s place them side-by-side. The core difference in the kyphosis vs lordosis debate is the direction and location of the abnormal spinal curve. Kyphosis is an exaggerated outward curve, primarily affecting the thoracic spine (upper back), leading to a hunched or rounded appearance. Lordosis, on the other hand, is an exaggerated inward curve, most commonly affecting the lumbar spine (lower back), resulting in a “swayback” where the buttocks protrude.

This fundamental difference in mechanics leads to different visual presentations and symptom profiles. A person with kyphosis may appear to be leaning forward, with rounded shoulders and a forward head posture. A person with lumbar lordosis will stand with a prominent arch in their lower back, their pelvis tilted forward. While both can cause back pain, the pain from kyphosis is typically localized to the upper and mid-back, while lordosis pain is centered in the lower back. Furthermore, severe kyphosis has a higher potential to impact internal organs like the lungs, whereas lordosis more commonly causes issues related to nerve compression in the lower spine, such as sciatica.

A Comparative Table: Kyphosis vs Lordosis

| Feature | Kyphosis | Lordosis |

|---|---|---|

| Curve Direction | Excessive outward curve (forward rounding) | Excessive inward curve (arching) |

| Primary Location | Thoracic spine (upper/mid-back) | Lumbar spine (lower back); can also be cervical (neck) |

| Common Visual Cue | Hunchback, rounded shoulders, forward head posture | Swayback, protruding abdomen and buttocks |

| Primary Symptoms | Upper back pain and stiffness, fatigue, breathing difficulties (in severe cases) | Lower back pain, muscle tightness, postural fatigue |

| Common Causes | Poor posture, Scheuermann’s disease, osteoporosis, degeneration | Obesity, pregnancy, muscle imbalances, spondylolisthesis |

| Typical Treatment Focus | Postural correction, strengthening upper back muscles, bracing (in adolescents), surgery for severe cases | Core strengthening, hip flexor stretching, weight management, surgery for severe cases |

The Interconnection: Can You Have Both?

The spine functions as an integrated unit, and a problem in one area often creates a compensatory issue in another. This is a critical concept that goes beyond a simple kyphosis vs lordosis comparison. It is very common for an individual to have both conditions simultaneously. For instance, a person with significant thoracic kyphosis will often develop a compensatory lumbar lordosis. Why? Because the body’s primary goal is to keep the head level and the eyes looking forward. If the upper back is hunched forward, the lower back must arch more inward to counterbalance the weight and prevent the person from falling forward.

This is known as a compensatory curve. Similarly, someone with a rigid, exaggerated lumbar lordosis might develop a compensatory thoracic kyphosis or changes in their cervical curve. This interplay means that a treatment plan must consider the entire spine, not just the most obvious curve. A physical therapist or spine specialist will always evaluate your global spinal alignment to address the root cause of the problem, rather than just treating a single symptom. Therefore, the question isn’t always kyphosis vs lordosis, but rather how they are interacting within a single individual’s spinal health picture.

Prevention and Proactive Spinal Health

Whether you are concerned about kyphosis, lordosis, or simply want to maintain a healthy back, the principles of prevention are remarkably similar. A proactive approach centered on strength, flexibility, and body awareness is your best defense against developing painful spinal conditions. It’s about building habits that support your spine throughout your daily life, from how you sit at your desk to how you exercise.

The foundation of spinal health is a strong core. The term “core” doesn’t just mean abdominal muscles; it includes the muscles in your back, sides, pelvis, and buttocks. These muscles act as a natural corset, stabilizing the spine and pelvis. When this muscular support system is weak, the spine is more vulnerable to abnormal curves. Incorporating exercises like planks, bridges, and bird-dogs into your routine can build incredible resilience. Equally important is flexibility, particularly in the hip flexors and hamstrings, which directly influence pelvic tilt and, consequently, the curvature of your lumbar spine.

The Role of Posture in Everyday Life

In our modern, sedentary world, posture is arguably the biggest factor in the development of postural kyphosis vs lordosis. Hours spent slouched over computers and looking down at phones train our bodies into positions that exaggerate spinal curves. The key is not to strive for a rigid, military-style posture all day, but to avoid sustained, static positions. Think about movement and variation. Set a timer to remind yourself to get up, walk around, and stretch every 30-60 minutes.

Ergonomics plays a huge role. Set up your workstation so that your computer monitor is at eye level, your knees are level with your hips, and your feet are flat on the floor. When standing, distribute your weight evenly on both feet. When sleeping, choose a supportive mattress and a pillow that keeps your neck in a neutral alignment. Mindful movement practices like yoga and Pilates are excellent for developing the body awareness and balanced muscle strength needed for good posture, helping to prevent both excessive kyphotic and lordotic curves.

When to See a Doctor

While minor aches and pains are common, certain signs warrant a visit to a healthcare professional. If you or a family member notices a visible, persistent hump in the upper back or a pronounced arch in the lower back, it’s a good idea to get it checked out. This is especially important for children and adolescents during growth spurts. You should also seek medical advice if you experience persistent back pain that doesn’t improve with rest, pain that radiates down your legs, or any neurological symptoms like numbness, tingling, or weakness.

Early intervention is almost always more effective. A doctor can provide an accurate diagnosis, rule out serious underlying conditions, and refer you to a specialist like an orthopedic surgeon or a physical therapist. Don’t fall into the trap of self-diagnosing based on internet information; a professional evaluation is crucial for distinguishing between kyphosis vs lordosis and creating a safe, effective treatment plan tailored to your specific needs.

Conclusion

The journey through the complexities of kyphosis vs lordosis reveals a clear takeaway: our spine’s health is a delicate balance. These conditions are not merely about “standing up straight,” but about understanding the profound interplay between bones, muscles, and nerves. Kyphosis, the excessive rounding of the upper back, and lordosis, the exaggerated arch of the lower back, are two sides of the same coin—expressions of spinal imbalance that can cause significant pain and functional limitations.

Ultimately, knowledge is power. By recognizing the differences and similarities between these conditions, you are better equipped to take charge of your spinal health. The path to prevention and management consistently leads back to foundational principles: building a strong and flexible core, practicing mindful posture in daily life, and seeking professional guidance when warning signs appear. Whether you are navigating a diagnosis or simply aiming for a healthier back, respecting the natural S-curve of your spine is the first step toward a lifetime of movement and comfort.

Frequently Asked Questions about Kyphosis and Lordosis

What is the main difference between kyphosis and lordosis?

The main difference lies in the direction and location of the abnormal spinal curve. Kyphosis is an excessive outward curvature, causing a rounded or hunched upper back. Lordosis is an excessive inward curvature, most often in the lower back, creating a “swayback” appearance with the buttocks protruding. So, the essential distinction in the kyphosis vs lordosis comparison is the direction of the curve: forward rounding versus an exaggerated arch.

Can poor posture alone cause kyphosis or lordosis?

Yes, poor posture is a primary cause of the most common forms of these conditions. Chronic slouching can lead to postural kyphosis, where the muscles and ligaments adapt to a rounded shoulder position. Similarly, consistently standing with a swayback (anterior pelvic tilt) can lead to postural lordosis. The good news is that because these forms are often flexible, they can frequently be improved with physical therapy, exercises, and conscious postural correction.

Are kyphosis and lordosis painful conditions?

They can be, but not always. Pain levels vary greatly depending on the severity and cause of the curvature. Many people with mild cases may experience little to no pain, perhaps just some muscle fatigue. However, as the curves become more pronounced, they can lead to muscle strain, stiffness, and aching pain localized to the affected area. In severe cases, the abnormal curvature can press on nerves or affect organ function, leading to more significant pain or other symptoms like leg numbness or shortness of breath.

How are kyphosis and lordosis typically treated?

The vast majority of cases are treated with non-surgical, conservative methods. The first line of defense is almost always physical therapy, which focuses on strengthening the muscles that support the spine (like the core and back muscles) and stretching tight muscles (like hip flexors or chest muscles). For adolescents with progressive kyphosis, a brace may be used. Pain is managed with anti-inflammatory medications. Surgery is reserved for the most severe cases where the curve is large, progressive, causing neurological problems, or not responding to conservative treatment.

Is it possible to have both kyphosis and lordosis at the same time?

Absolutely. In fact, it’s quite common. The spine works as a whole, and an abnormality in one area often leads to a compensatory curve in another. For example, a significant thoracic kyphosis (hunched upper back) will frequently cause the body to develop a compensatory lumbar lordosis (exaggerated lower back arch) to help keep the head balanced over the pelvis. This is a key reason why a full spinal evaluation is necessary, as treatment may need to address both curves in the kyphosis vs lordosis dynamic.