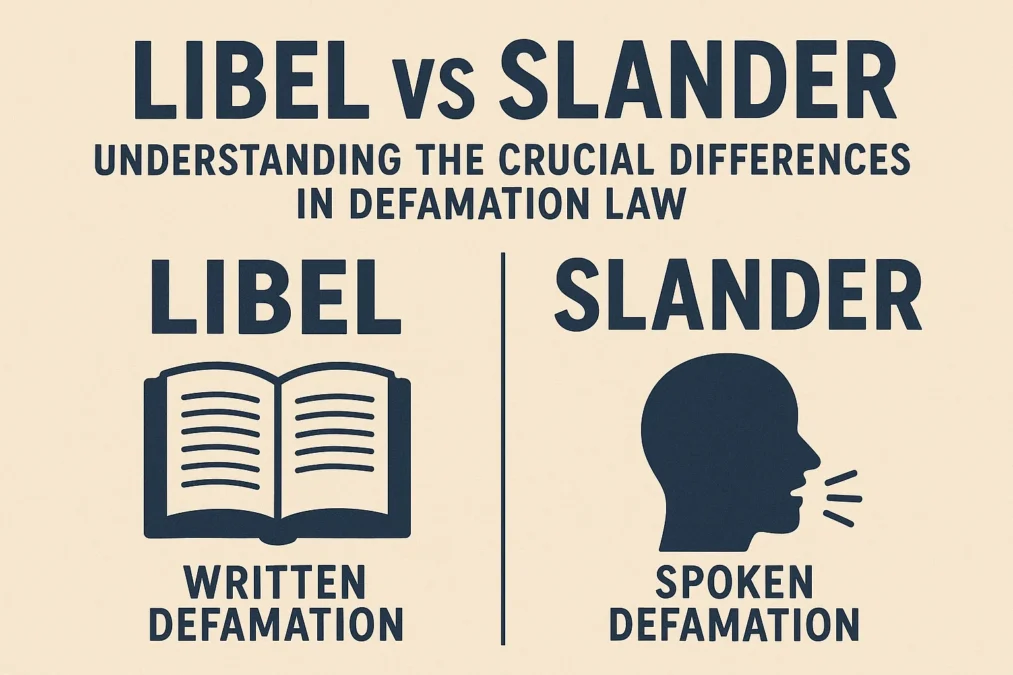

Libel vs Slander: You’ve probably heard the terms thrown around in news stories, legal dramas, or even in heated online arguments: libel and slander. They both fall under the umbrella of defamation—the act of harming someone’s reputation by making false statements. But what exactly sets them apart? While they share the same core goal of protecting a person’s good name, the legal distinction between libel and slander is more than just semantic jargon; it’s a fundamental concept that can determine the outcome of a lawsuit.

In our hyper-connected world, where a tweet can go viral in minutes and a Facebook post can be seen by millions, understanding the nuances of defamation law is more critical than ever. A single false statement, whether written in a newspaper or spoken on a podcast, can have devastating consequences for the subject’s personal life, career, and mental well-being. This article will be your comprehensive guide. We will dive deep into the worlds of libel and slander, unraveling their definitions, exploring their histories, and examining how they apply in the digital age. By the end, you’ll not only know the difference but also understand why that difference matters so much in a court of law.

Defining Defamation: The Big Picture

Before we can distinguish between libel and slander, we need to understand the larger category they belong to: defamation. At its heart, defamation is a civil wrong (a “tort”) that involves communicating a false statement to a third party, which causes harm to the reputation of the person it’s about. The law operates on the principle that every person has a right to their good name and should be protected from malicious lies. However, this right is balanced against another fundamental right: freedom of speech. This tension is what makes defamation law so complex and fascinating.

For a statement to be legally considered defamation, the person bringing the lawsuit (the plaintiff) must typically prove several key elements. These generally include that the statement was false, that it was communicated to someone else (this is called “publication” in legal terms, even if it’s just telling one person), that the person making the statement was at fault, and that it resulted in some kind of harm. It’s crucial to note that opinions are generally protected speech and are not considered defamatory. Saying, “I think John is a terrible chef” is an opinion. But falsely telling a crowd, “John uses rotten ingredients in his restaurant,” is a factual assertion that could be defamatory.

What is Libel? The Written Record

Let’s start with libel. Libel is defamation that is written, printed, or otherwise published in a fixed, tangible form. The key characteristic of libel is its permanence. Because it is recorded, it can be revisited, shared, and preserved, often leading to wider and more lasting damage. Think of it as defamation you can point to, hold in your hand, or link to online. Historically, libel has been viewed by courts as the more serious of the two forms of defamation precisely because of this enduring nature.

Examples of libel are all around us in the modern media landscape. A false and damaging article in a newspaper or magazine is a classic case of libel. Similarly, a defamatory post on social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, or LinkedIn constitutes libel. Other examples include false statements in a book, a blog post, a Google review, an email sent to multiple people, a defamatory comment on a YouTube video, or even a caption under a photograph. Because the internet never forgets, online libel can be particularly destructive, with the potential to resurface and cause harm years after it was first posted.

What is Slander? The Spoken Word

On the other side of the defamation coin is slander. Slander is defamation that is spoken or expressed through some other transient form. It is oral and temporary, vanishing into the air after it is uttered. This fleeting quality is the defining feature of slander and the primary reason it has traditionally been treated as less inherently harmful than libel. The damage from slander often relies more heavily on the immediate context and the reach of the speaker.

Common examples of slander include false statements made during a public speech, a rant on a live television or radio broadcast that isn’t scripted, damaging rumors spread verbally at a workplace, or false accusations shouted in a public meeting. Imagine a person standing on a soapbox in a park and falsely claiming a local business owner is a thief, or a former employee telling a potential employer at a coffee shop that their old boss is under federal investigation. These are instances of slander. The temporary nature makes it harder to prove, as there is often no permanent record, requiring witnesses to testify about what was actually said.

The Historical Divide Between Libel and Slander

The distinction between libel and slander is not a modern invention; it has deep roots in English common law, which forms the basis of the American legal system. Centuries ago, the courts drew a clear line between the two, primarily based on the potential for harm. Written defamation was considered far more dangerous because the printing press allowed for the mass distribution of falsehoods, capable of reaching a vast audience and permanently tarnishing a reputation. Spoken words, by contrast, were seen as a more local and temporary nuisance.

This historical context led to the development of different legal rules for each. In many cases, libel was considered actionable “per se,” a Latin term meaning “in itself.” This meant that a plaintiff in a libel case did not necessarily have to prove they suffered specific financial losses; the very existence of the published falsehood was enough to presume harm. For slander, however, the plaintiff almost always had to prove they suffered actual monetary damage as a result of the spoken words, except in a few specific, severe categories which we will explore later.

The Core Legal Differences Explained

So, why does the libel vs slander distinction still matter today? It primarily boils down to two critical legal concepts: permanence and the requirement to prove damages. Libel, being fixed and permanent, is often treated as a more serious offense from the get-go. The law recognizes that a written lie has a longer shelf life and a greater potential for repeated harm. Because of this, in many jurisdictions, a plaintiff suing for libel may not have the initial burden of proving they suffered specific financial losses; the harm is inferred from the publication itself.

Slander, with its transient nature, typically places a higher burden of proof on the plaintiff. In a pure slander case, the person bringing the lawsuit usually must provide concrete evidence of the financial harm they suffered as a direct result of the false statement. For instance, if someone falsely tells your clients that you have declared bankruptcy, and you can show that you lost three major contracts because of that rumor, you have proven your “special damages.” This key difference in the burden of proof is often the deciding factor in whether a defamation case is worth pursuing.

When Slander is Treated as Seriously as Libel

While the general rule requires proving special damages for slander, the law has long recognized that certain types of false spoken statements are so inherently damaging that they are treated like libel. These categories are known as slander per se. In these cases, the law presumes that harm occurred, and the plaintiff does not need to prove specific financial loss. The four traditional categories of slander per se are accusations that impute:

- The commission of a crime involving moral turpitude (a serious or morally reprehensible act).

- The existence of a loathsome disease (historically, like leprosy or venereal disease, but now may include serious STIs).

- Allegations that seriously harm a person’s professional reputation, business, or trade (e.g., falsely stating a doctor is a fraud or a banker is embezzling funds).

- Accusations of unchastity (a category that is less commonly applied or has been modified by modern statutes).

For example, if you publicly and falsely announce that a certified public accountant has been convicted of tax fraud, that statement would likely qualify as slander per se. The accusation directly attacks their professional integrity, and the law would presume it caused harm without the accountant having to immediately produce a list of lost clients.

Proving a Defamation Case: The Plaintiff’s Burden

Whether dealing with libel or slander, a plaintiff must successfully prove a set of core elements to win their case. The exact requirements can vary by state, but they generally include the following. First, the statement must be false. Truth is an absolute defense to a defamation claim. If the statement is substantially true, the case fails. Second, it must have been “published,” meaning communicated to at least one other person besides the speaker and the subject.

Third, the statement must be “of and concerning” the plaintiff, meaning a reasonable person would understand it to be about them. It doesn’t need to name them explicitly. Fourth, the plaintiff must generally show that the defendant was at fault. For private figures, this usually means proving negligence—that the speaker didn’t exercise reasonable care in determining the truth. For public officials or public figures, the bar is much higher; they must prove “actual malice”—that the statement was made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard for the truth. This high standard, established in the landmark 1964 case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, protects robust public debate.

The Critical Role of Public Figures vs. Private Figures

One of the most important concepts in modern defamation law is the distinction between public and private figures. This distinction dramatically affects what the plaintiff must prove. A public figure is someone who has achieved widespread fame or notoriety or has thrust themselves into the forefront of a particular public controversy to influence its resolution. Celebrities, politicians, and high-profile business leaders typically fall into this category.

As mentioned, public figures must prove “actual malice” to win a defamation case, whether it’s for libel or slander. This is a incredibly high bar to clear. They must show that the defendant knew the statement was false or likely false but said it anyway. This protects the media and individuals when commenting on matters of public concern, even if they get things wrong occasionally. A private figure, an ordinary person not in the public eye, has a much easier path. They usually only need to prove that the defendant was negligent—that they failed to act with the level of care a reasonable person would have in the same situation. This is a much lower standard of fault.

Defenses to Libel and Slander Claims

Even if a statement is false and damaging, a defendant in a defamation lawsuit has several potential defenses. The most powerful and complete defense is truth. If the defendant can prove the substantive truth of their statement, the case will be dismissed. Another key defense is privilege. Certain communications are considered “privileged” and are protected from defamation claims to encourage free and candid discussion in important settings. For example, statements made by lawmakers during legislative debates or by witnesses in a court proceeding are absolutely privileged.

A qualified privilege may exist in other situations, such as when an employer gives a reference for a former employee. As long as the statement is made in good faith and without malice, it may be protected. Opinion is also a defense, but the line between fact and opinion can be blurry. A pure statement of opinion (“I think that actor is terrible in every role”) is not defamatory. However, a statement that implies undisclosed defamatory facts (“I think that mayor is corrupt”) may be actionable if presented as a conclusion based on unstated false facts. Finally, consent is a full defense; if you give someone permission to publish a statement about you, you cannot later sue them for it.

Libel, Slander, and the Digital Age

The internet has fundamentally blurred the traditional lines between libel and slander, creating new challenges for courts and legal scholars. Is an unscripted, defamatory remark on a live-streamed video slander because it’s spoken, or is it libel because it’s captured in a permanent digital recording? What about a voice message or a podcast? The modern trend is to treat most online defamation as libel, given its fixed and durable nature. A tweet is text, a YouTube video is a recording, and a Facebook post is published text—all are tangible in the digital realm.

This has led to a massive increase in the potential impact of defamatory statements. A single post can be seen by a global audience instantly, making the damage from online libel more severe than ever before. Furthermore, the internet complicates jurisdictional issues. If someone in California posts a libelous statement on a server in Texas that is read by someone in New York, where can the lawsuit be filed? These are the complex questions that courts are still grappling with today, and the legal landscape continues to evolve as technology advances.

Real-World Examples and Case Studies

To truly grasp the concepts of libel and slander, it helps to look at real-world scenarios. Imagine a local newspaper publishes a story falsely accusing a small-town baker of using sawdust in their bread. The bakery loses all its customers and is forced to close. This is a clear case of libel. The statement is written, published in a tangible form, and has caused direct financial harm. The baker, a private figure, would likely sue for libel, alleging the newspaper was negligent in its fact-checking.

Now, consider a scenario at an office party. A disgruntled employee, angry that they were passed over for a promotion, loudly tells a group of coworkers that the manager who got the promotion was fired from their last job for sexual harassment. This statement is completely false. The rumor spreads through the company, and the manager is ostracized and suffers severe emotional distress. This is slander. However, because the accusation is one of a serious crime (sexual harassment), it would likely be considered slander per se, meaning the manager would not have to prove specific financial losses; the harm would be presumed.

How to Protect Yourself from Defamation Claims

In an era where everyone has a publishing platform, it’s essential to be mindful of what you say and write. The best way to avoid a libel or slander lawsuit is to always verify your facts before sharing information, especially if it is negative or could harm someone’s reputation. Be particularly cautious when repeating rumors or hearsay. If you are a blogger or active on social media, make a habit of fact-checking from reliable sources before you post.

When expressing negative views, frame them clearly as your opinion rather than stating them as facts. Instead of writing, “John Smith is a con artist,” you could write, “Based on my experience, I believe John Smith’s business practices are dishonest.” The latter is more clearly an opinion, though it is not an absolute shield. Furthermore, be aware of contexts where a qualified privilege might apply, such as when giving a professional reference, and stick to relevant, truthful information. A little caution can prevent a long and costly legal battle.

What to Do If You Are a Victim of Defamation

Discovering that someone has spread a damaging lie about you can be emotionally devastating and have real-world consequences. If you believe you are a victim of libel or slander, your first step should be to document everything. For libel, take screenshots of the posts, articles, or reviews, ensuring you capture the URL and the date. For slander, write down exactly what was said, when and where it was said, and the names of any witnesses who heard it.

Your next step is often to send a cease-and-desist letter or a retraction demand from an attorney. This formally notifies the person of the defamatory statement, demands they stop publishing it, and often requests a public correction or retraction. In many cases, this can resolve the issue without going to court. If it doesn’t, you will need to consult with a defamation attorney to discuss the merits of your case, including whether you can prove the statement was false, the fault of the defendant, and the damages you have suffered. They can advise you on the strength of your claim and the likelihood of success.

Emigrate vs Immigrate: The Ultimate Guide to Getting These Tricky Words Right

The Global Perspective on Defamation

It’s important to remember that defamation law is not uniform across the globe. The United States, with its strong First Amendment protections for freedom of speech, is generally considered to have plaintiff-friendly defamation laws. Other countries, particularly the United Kingdom, are known for having laws that are much more favorable to the person bringing the lawsuit. In the UK, for instance, the burden of proof often shifts to the defendant to prove the truth of their statement, rather than the plaintiff having to prove its falsity.

This difference has led to a phenomenon known as “libel tourism,” where plaintiffs choose to file their lawsuits in jurisdictions with the strictest defamation laws, even if their connection to that country is minimal. For publishers and individuals with an international audience, this means a single statement could lead to lawsuits in multiple countries, each with its own legal standards for libel and slander. Understanding these international variations is crucial for global businesses and media organizations.

The Future of Libel and Slander Law

The law is never static, and defamation law is continuously evolving to keep pace with societal and technological changes. We are likely to see ongoing legal battles over the responsibilities of social media platforms for the content posted by their users. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act in the U.S. currently provides broad immunity to these platforms, but there is increasing political pressure to reform it.

Furthermore, the rise of deepfakes—highly realistic, AI-generated video and audio forgeries—presents a terrifying new frontier for defamation. How will courts handle a case where a damaging video of a person is completely fabricated? It will likely be treated as a form of libel (since it’s a fixed recording), but the challenges of proving falsity and malice will be immense. As our tools for communication become more powerful, so too do the tools for destruction of reputation, ensuring that the legal concepts of libel and slander will remain critically relevant for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion Libel vs Slander:

Navigating the legal landscape of libel and slander is complex, but the fundamental distinction is clear: libel is written defamation, fixed in a tangible form, while slander is spoken, transient defamation. This difference, rooted in centuries of common law, continues to have profound implications, particularly in the burden of proving harm. Libel often presumes damage, while slander typically requires proof of specific financial loss, unless it falls into one of the severe “slander per se” categories.

In today’s digital world, the lines are blurring, but the core principles hold true. The internet has amplified the reach and permanence of defamatory statements, making understanding these concepts more important than ever. Whether you are a content creator, a business professional, or simply an engaged citizen, being mindful of the difference between fact and opinion, and the real-world harm that false statements can cause, is essential. Ultimately, the laws of libel and slander exist to strike a delicate balance—protecting individuals from reputational harm while safeguarding our fundamental right to free expression.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main difference between libel and slander?

The main difference between libel and slander lies in the form the defamation takes. Libel refers to defamatory statements that are written, printed, or published in a permanent form, such as in a newspaper, a blog post, or on social media. Slander, on the other hand, refers to spoken defamatory statements, which are temporary, like a rumor spread verbally or an unscripted comment on a live broadcast. The legal implications differ, primarily in how damages are proven.

Can you be sued for libel or slander on social media?

Absolutely. Defamatory statements made on social media platforms like Facebook, X (Twitter), or Instagram are almost universally considered libel, not slander. This is because the posts are in a written, fixed, and tangible digital form. The same legal principles apply: if you post a false statement of fact that harms someone’s reputation, and you were at fault in doing so, you can be sued for libel. The widespread nature of social media can even exacerbate the damages.

Is it harder to win a slander case than a libel case?

Generally, yes, it can be more challenging for a plaintiff to win a pure slander case. This is because, in many jurisdictions, for standard slander, the plaintiff must prove they suffered specific financial losses (special damages) as a direct result of the spoken words. In a libel case, or in a slander per se case (involving accusations of crime, loathsome disease, etc.), the law often presumes that harm occurred, so the plaintiff doesn’t have that initial burden of proving monetary loss.

Are opinions considered libel or slander?

No, pure expressions of opinion are generally not considered libel or slander and are protected under free speech principles. The key is that the statement must be presented as an assertion of fact. For example, saying “I think that movie was terrible” is an opinion. But saying “The director of that movie stole money from the production budget” is an assertion of a specific, verifiable fact. If false, that factual assertion could be defamatory. The line between fact and opinion can sometimes be very fine and is often a central point of contention in defamation lawsuits.

What should I do first if someone has defamed me?

If you believe you have been a victim of libel or slander, your first step should be to diligently collect evidence. For libel, take screenshots with full URLs and timestamps. For slander, write a detailed account of what was said, including the date, location, context, and names of any witnesses. Do not engage in retaliatory defamation. Then, consult with an attorney who specializes in defamation law. They can advise you on the strength of your case and often begin by sending a formal cease-and-desist letter to the person responsible.

Comparison Table: Libel vs. Slander

| Feature | Libel | Slander |

|---|---|---|

| Form | Written, printed, or fixed in a tangible form (e.g., book, article, social media post). | Spoken or transient (e.g., speech, verbal rumor, live broadcast). |

| Permanence | Permanent and durable. Can be revisited and shared. | Temporary and fleeting. Vanishes after it is uttered. |

| Typical Burden of Proof for Damages | Harm is often presumed (actionable per se). Plaintiff may not need to prove specific financial loss. | Plaintiff must usually prove specific financial loss (special damages), unless it’s slander per se. |

| Examples | A false Google review, a defamatory newspaper article, a harmful Facebook post. | A false rumor spread at a party, an unscripted defamatory remark on a podcast, a verbal false accusation to a employer. |

| Historical Severity | Considered more serious due to potential for widespread, lasting damage. | Considered less serious historically due to its transient nature. |

Quotes on Defamation

“A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

— Often attributed to Mark Twain, this quote perfectly captures the destructive potential of defamation, especially in the age of the internet.“Reputation is an idle and most false imposition; oft got without merit, and lost without deserving.”

— William Shakespeare, Othello. This highlights the fragile nature of reputation, which defamation law seeks to protect.“The right to be let alone is the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.”

— Justice Louis Brandeis. This foundational idea of privacy underpins the harm caused by libel and slander, which intrude upon one’s personal and professional standing.