Walking along a roadside or through a meadow, you’ve likely seen them—tall, lacy white flowers nodding in the breeze. They look delicate, beautiful, and almost interchangeable. But within this sea of white umbels lies a botanical tale of two plants: one is a benign and beautiful wildflower, while the other is one of the most notoriously poisonous plants in North America. The ability to distinguish between poison hemlock vs queen anne’s lace isn’t just a party trick for plant enthusiasts; it’s a critical skill for foragers, gardeners, hikers, and anyone who spends time outdoors. A single misidentification can have fatal consequences.

This comprehensive guide is designed to be your ultimate resource. We will peel back the layers of these two visually similar plants, diving deep into their histories, biology, and, most importantly, the key identifying features that set them apart. We’ll move beyond a simple list of differences and build a holistic understanding, giving you the confidence to tell them apart at a glance. We’ll explore the stories behind their names, the science of their toxicity, and what to do if you suspect an encounter has gone wrong. By the end of this article, the once-confusing white flowers will reveal their distinct identities, and you’ll be equipped with the knowledge to navigate the natural world more safely.

The Stakes Are High: Why This Distinction Matters So Much

Before we get into the specific details of stems and spots, it’s crucial to understand the gravity of the situation. Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) is not a plant to be trifled with. It contains a suite of potent neurotoxins, with coniine being the most famous. Coniine directly attacks the central nervous system. Ingestion, even in small amounts, can lead to a rapid progression of symptoms including trembling, salivation, dilated pupils, muscle paralysis, and ultimately, respiratory failure. There is no antidote. Treatment is supportive, focusing on keeping the airway open and assisting with breathing, but the paralysis can be so profound that it is often fatal.

The history of poison hemlock is steeped in death. It is the plant that was used to execute the famous Greek philosopher Socrates in 399 BC. Ancient accounts describe his death as a gradual paralysis starting at his feet and moving upward, a classic presentation of coniine poisoning. This historical context isn’t just a fun fact; it’s a stark reminder that humans have understood the deadly potential of this plant for millennia. Every part of the plant—roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and seeds—is toxic, and the poison can even be absorbed through the skin for some people, causing dermatitis and systemic issues, so handling it without gloves is strongly discouraged.

In contrast, Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota) is the wild ancestor of the cultivated carrot we buy in grocery stores. Its roots, especially when young, are edible and smell distinctly of carrot. The leaves are also edible, though they can be somewhat bitter. For foragers, it’s a wonderful wild edible, used in salads, soups, and as a flavoring agent. The fundamental, life-or-death difference between these two plants makes accurate identification not just a matter of botanical curiosity, but one of personal safety. Mistaking the former for the latter is a error you simply cannot afford to make.

A Tale of Two Histories and Habitats

Understanding where these plants come from and where they like to grow provides the first layer of context in telling them apart. While both are often found in similar disturbed areas, their origins and growth patterns offer subtle clues.

Poison hemlock is a native of Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia. It was introduced to North America as an ornamental plant, a fact that seems shocking today given its toxicity. It has since escaped cultivation and become a highly invasive species, colonizing roadsides, ditches, stream banks, and abandoned fields with alarming speed. It thrives in moist, disturbed soils and is often one of the first plants to spring up in a vacant lot or along a new construction right-of-way. It is a biennial plant, meaning it completes its life cycle over two years. In the first year, it focuses energy on growing a low rosette of leaves. In the second year, it sends up the tall, flower-topped stalk, sets seed, and then dies.

Queen Anne’s Lace, also known as Wild Carrot, shares a similar Eurasian origin but has a much longer and more benign relationship with humans. It is the progenitor of the domestic carrot; centuries of selective breeding for a larger, sweeter, less woody root gave us the orange vegetable we know today. Like poison hemlock, it is a biennial and thrives in sunny, disturbed areas like meadows, roadsides, and field edges. However, it is generally less tied to consistently moist soils than poison hemlock and can be found in drier pastures and prairies. Its presence is often a sign of land in transition, and it plays a role in ecological succession, helping to stabilize soil before shrubs and trees move in.

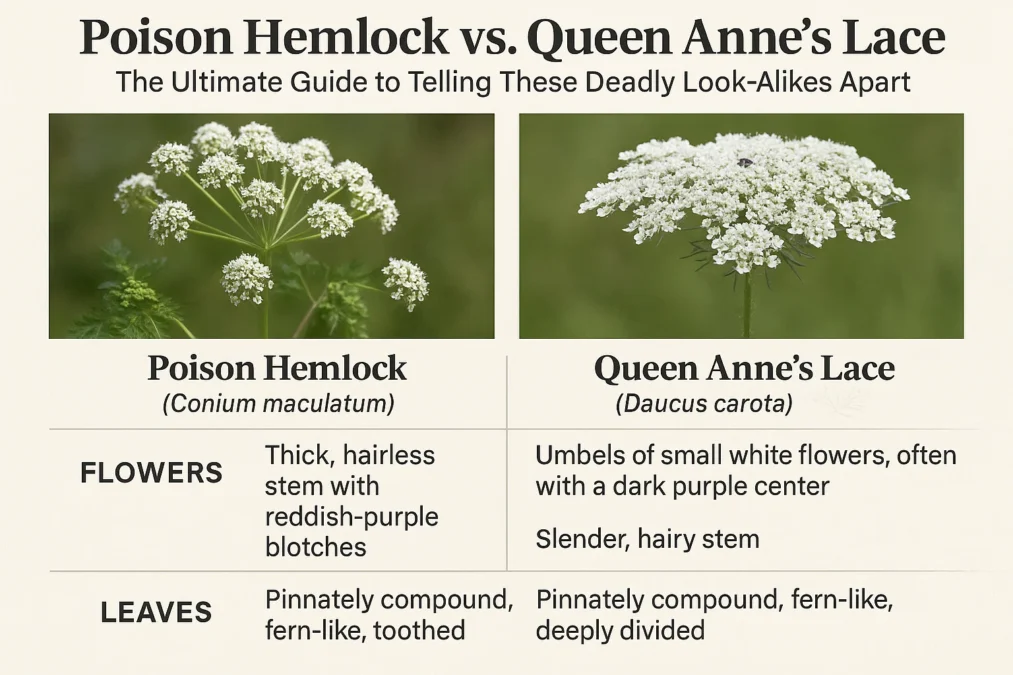

The Devil’s in the Details: A Head-to-Head Identification Guide

This is the core of the matter. While a quick glance from a moving car might leave you confused, a closer, systematic inspection will reveal a world of difference. We will break down the comparison by plant part, creating a mental checklist you can run through whenever you encounter a suspect plant.

The Stem: The Most Reliable Giveaway

The stem is, without a doubt, the single most reliable and easiest feature to use when distinguishing between these two plants. If you learn only one thing from this guide, let it be the characteristics of the stem.

Poison hemlock boasts a stem that is hairless, or glabrous, and strikingly smooth. Its most definitive feature is the presence of prominent purple or reddish-brown splotches and blotches. These spots are irregular and can look almost like paint splatters or bruises all over the stem, particularly concentrated at the lower nodes (the points where leaves branch off). The stem itself is also hollow between the nodes. This combination—hairless, smooth, with purple splotches, and hollow—is the hallmark of poison hemlock. It’s a warning sign written in nature’s color code.

Queen Anne’s Lace, on the other hand, presents a stem that is almost the complete opposite. It is distinctly hairy or fuzzy, feeling slightly rough to the touch. It is entirely green and lacks any purple splotches or spots. Furthermore, the stem of Queen Anne’s Lace is solid, not hollow. This hairy, solid, green stem is a clear indicator that you are likely looking at the benign wild carrot. The hairiness is sometimes described as being covered in fine bristles, which is a great tactile clue if you’re comfortable and safe touching the plant (always be sure of your ID before handling).

The Leaves: A Study in Lacy Similarity

The leaves of both plants are lacy and fern-like, which is a primary source of the confusion. They are both pinnately compound, meaning the leaf is divided into a series of smaller leaflets arranged on opposite sides of a central stalk. However, with a trained eye, you can see the differences.

Poison hemlock leaves are triangular in overall shape and have a lacy, delicate appearance. They are pinnately compound, but the leaflets are further divided into finer, more delicate segments, giving them a almost feathery look. The leaves themselves are hairless and smooth, mirroring the stem. When crushed, they are often described as emitting a musty, unpleasant odor, sometimes compared to mouse urine or the smell of a parsnip that has gone bad. This odor is a key warning sign.

Queen Anne’s Lace leaves are also pinnately compound and fern-like, but they are more linear or lance-shaped in their overall outline. The leaflets are generally broader and less finely dissected than those of poison hemlock. Crucially, the leaves of Queen Anne’s Lace are also hairy, continuing the theme from the stem. Most notably, when you crush a Queen Anne’s Lace leaf, it releases a strong, unmistakable scent of carrot. This aromatic signature is a powerful and safe identifying tool.

The Flowers: White Umbrels with Hidden Clues

From a distance, both plants produce a large, flat-topped cluster of tiny white flowers called an umbel. This is a classic characteristic of the Apiaceae or carrot family, to which both belong. But up close, the differences become apparent.

A poison hemlock flower umbel is typically more loose and spreading. The individual umbels are often more numerous and can create a more rounded, dome-shaped overall flower head. The flowers are pure white and lack any of the colorful flourishes found on its look-alike. There are no bracts (leaf-like structures) beneath the main flower cluster, or if present, they are small and inconspicuous. The plant tends to bloom a little earlier in the summer than Queen Anne’s Lace in many regions.

Queen Anne’s Lace has a flower cluster that is often, but not always, flatter on top, like a doily. The most famous and charming identifier is the frequent presence of a single, dark purple-red floret in the very center of the white umbrella. The story goes that Queen Anne of England (1665-1714) pricked her finger while sewing the lace, and a single drop of blood fell in the center. While a lovely tale, this feature is not always present, so it should not be relied upon alone. A more consistent feature is the presence of prominent, green, forked bracts that curl upwards and surround the base of the main flower cluster. These bracts look like a lacy collar or a bird’s nest supporting the flowers and are a key identifier.

Greenshell Mussels vs Black Mussels: The Ultimate Seafood Showdown

The Roots and Scent: The Ultimate Test

This is the most definitive test, but it requires you to be absolutely certain you are not dealing with poison hemlock before proceeding. This should only be done after confirming all other identifying features point safely to Queen Anne’s Lace.

The root of poison hemlock is a white, fleshy taproot. It does not smell like a carrot. If crushed, it may emit the same unpleasant, musty odor as the leaves. It is deadly and should never be tasted or ingested.

The root of Queen Anne’s Lace is a thin, woody taproot that is usually off-white or light tan in color. Its most famous characteristic is its powerful and pleasant aroma. If you carefully dig up a small portion and crush it, it will smell distinctly, unmistakably, like a carrot. This is the wild ancestor of our domestic carrot, and the scent is the final, confirming piece of evidence. Again, only attempt this if you are 100% confident based on stem, leaf, and flower characteristics that you have Queen Anne’s Lace.

The Carrot Family Connection: A Dangerous Dynasty

Both poison hemlock and Queen Anne’s Lace belong to the Apiaceae family, formerly known as the Umbelliferae. This is a massive plant family that includes many of our favorite culinary herbs and vegetables, like carrots, celery, parsley, cilantro, dill, and fennel. The family is characterized by its distinctive flower structure—the umbel. Unfortunately, this family also harbors some of the most deadly plants in the world.

This is why using a single characteristic, like the flower shape, is so dangerous. You cannot assume a plant is safe because it looks like dill or parsley. The Apiaceae family is a classic example of “botanical doppelgangers,” where edible and lethally toxic species can look remarkably similar, especially in their first-year growth stages when only the leaves are present. Other dangerous members of this family include water hemlock (Cicuta species), which is considered even more toxic than poison hemlock, and giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum), whose sap causes severe phototoxic burns on the skin.

This familial relationship is the very reason why foragers must be exceptionally careful and learn to identify plants using a multi-faceted approach. Never rely on a single feature. Always cross-reference the stem, leaves, flowers, habitat, and scent before even considering consumption of any wild plant from this family.

Ecological Roles and Garden Considerations

Despite their dangers or weedy reputations, both of these plants play a role in their ecosystems, though one is far more beneficial than the other.

Poison hemlock, as an invasive species, often forms dense monocultures that crowd out native vegetation. It has few natural predators in North America due to its toxicity, which allows it to spread unchecked. However, it is not without ecological function. Some specialized insects, like the Poison Hemlock Moth (Agonopterix alstroemeriana), have evolved to feed on it exclusively, sequestering the toxins for their own defense. Generally, though, its presence is a sign of a disturbed ecosystem, and management is often recommended, especially in areas frequented by people or livestock.

Queen Anne’s Lace is also non-native and can be weedy, but it is generally not as aggressively invasive as poison hemlock. It is a fantastic plant for pollinators. Its broad, flat flower clusters are perfect landing pads for a wide variety of insects, including bees, wasps, beetles, and tiny beneficial wasps. Its seeds are a food source for birds like the American Goldfinch. In a wildflower garden, it can be allowed to grow to support local wildlife, though many gardeners prefer to manage it to prevent it from self-seeding too vigorously.

Safe Removal and Management

If you find poison hemlock on your property, it is wise to remove it, especially if you have children, pets, or livestock.

Removal must be done with extreme caution. Always wear gloves, long sleeves, long pants, and closed-toe shoes. Avoid touching your face while handling the plant. For small infestations, digging out the taproot is effective; ensure you remove the entire root to prevent regrowth. The best time to do this is in the first year when the plant is a low rosette and easier to manage, but be extra vigilant with identification at this stage. For larger infestations, cutting the plant before it sets seed can help control its spread, but dispose of the cuttings securely in the trash, not in compost. For significant problems, consulting a professional landscaper or your local extension office is recommended.

Managing Queen Anne’s Lace is a matter of preference. If you wish to keep it, simply enjoy its beauty and the pollinators it brings. If you consider it a weed, it can be pulled easily, or the flower heads can be deadheaded before they go to seed to prevent them from spreading. Since it is not toxic, handling it is safe and straightforward.

A Comparative Table at a Glance

This table summarizes the key differences for a quick side-by-side comparison.

| Feature | Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum) | Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota) |

|---|---|---|

| Stem | Hairless, smooth, with prominent purple/red splotches; hollow | Hairy or bristly, completely green; solid |

| Leaves | Fern-like, triangular, finely divided; hairless; unpleasant, musty odor when crushed | Fern-like, more linear; hairy; strong carrot scent when crushed |

| Flowers | White umbels, often more loose and dome-shaped; no bracts or small, inconspicuous ones | White umbels, often flatter; often a single purple floret in center; prominent green, forked bracts at base |

| Root | White taproot; no carrot smell | Thin, woody taproot; strong carrot smell |

| Height | Can grow very tall, often 6-10 feet | Typically 2-4 feet tall |

| Toxicity | Extremely toxic; can be fatal if ingested | Non-toxic; root and leaves are edible |

Voices from the Field

The importance of this distinction is echoed by experts and enthusiasts alike.

A master botanist once noted, “In the world of foraging, assuming makes an… well, you know the rest. With the Apiaceae family, there is no room for error. The difference between a wild carrot and a deadly poison is a few minutes of careful study.”

An experienced herbalist shared this wisdom: “We teach our students to use all their senses. The sight of a purple-spotted stem, the feel of a hairless leaf, and the smell of a musty root are all red flags. Nature provides the clues; we just have to learn to read them.”

Conclusion

The journey through the world of poison hemlock vs queen anne’s lace is a powerful lesson in botanical literacy. What begins as a confusion of white lace flowers ends with a clear understanding of two fundamentally different organisms. The hairy, solid green stem of Queen Anne’s Lace stands in stark contrast to the smooth, purple-blotched, hollow stalk of poison hemlock. The carrot scent of one is a welcoming aroma, while the musty odor of the other is a warning. The presence of a single purple floret and a lacy collar of bracts offers charming clues to the safe wildflower.

This knowledge is more than academic; it is empowering. It allows you to walk through a meadow or down a country lane with a deeper appreciation for the complexity of the natural world and the confidence to interact with it safely. You can admire the delicate beauty of Queen Anne’s Lace, knowing its connection to your dinner plate, and you can give a wide, respectful berth to the tall, imposing poison hemlock, understanding its deadly legacy. The key takeaway is to always be observant, be methodical, and never rely on a single characteristic. When in doubt, the safest rule is to admire their beauty from a distance and leave the plant exactly as you found it.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I be absolutely sure I’m identifying Queen Anne’s Lace and not poison hemlock?

Absolute certainty comes from a combination of factors, not just one. First and foremost, check the stem. A hairy, completely green, and solid stem points toward Queen Anne’s Lace. The absence of any purple splotches is a huge relief. Then, look for the green, forked bracts under the flower head and check for a potential single purple floret in the center. Finally, if you are confident based on these other signs, crush a leaf. The definitive, pleasant smell of carrot will confirm your identification. If any of these features are missing, or if the stem has purple spots, err on the side of caution and assume it’s poison hemlock.

I touched a plant I think was poison hemlock. What should I do?

For most people, simply touching poison hemlock is not dangerous, as the toxins need to be ingested or to enter the bloodstream through a cut to cause systemic poisoning. However, the sap can cause skin irritation, contact dermatitis, or phytophotodermatitis in some individuals, similar to other members of the carrot family. If you have touched it, the first step is to remain calm. Wash the affected area thoroughly with soap and cool water as soon as possible. Avoid touching your eyes or mouth. Monitor the area for any rash or irritation. If you experience any systemic symptoms like nausea, dizziness, or rapid heartbeat, or if you had a cut on your hand and are concerned, seek medical attention immediately and, if possible, take a photo of the plant to show the doctor.

Are there any other plants that look like poison hemlock and Queen Anne’s Lace?

Yes, the Apiaceae family is full of look-alikes. Two other important ones are Water Hemlock (Cicuta spp.), which is even more toxic than poison hemlock and prefers very wet habitats, and Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa), which has a yellow flower cluster and sap that can cause severe burns when exposed to sunlight. Cow Parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris) is another common white-flowered look-alike found in many regions. This is why it’s so critical to not just know what Queen Anne’s Lace looks like, but to be able to rule out all the dangerous imposters using a full suite of characteristics.

Is it safe to grow Queen Anne’s Lace in my garden if I have pets?

Generally, Queen Anne’s Lace itself is considered non-toxic to dogs and cats. The ASPCA does not list it as a plant of concern for pets. However, the danger lies in misidentification. If you are planting it in an area where your pets roam, you must be 100% certain that it is indeed Queen Anne’s Lace and that no poison hemlock or other toxic look-alikes are growing nearby, which your pet could accidentally ingest. Given the risks, many pet owners choose to avoid planting it altogether to eliminate any chance of a tragic mistake.

What is the best time of year to tell these plants apart?

You can identify them throughout their growing cycle, but the most reliable time is during their flowering period, typically from late spring through summer. This is when all the key features—stem, leaves, and flowers—are fully present and observable. First-year plants, which exist as low rosettes of leaves, are much more difficult to distinguish, and it is highly recommended that beginners avoid trying to identify or forage any Apiaceae plant in its first-year stage. When in doubt, waiting for the plant to mature and show its flowers and full stem is the safest approach.